This isn't weird looking. It's what normal MCU code actually looks like.

Arduino code is the weird stuff, with functions that access the MCU control registers indirectly. While this is somewhat "nicer" looking, it's also much slower, and uses a lot more program space.

The mysterious constants are all described in great detail in the ATmega328P datasheet, which you really should read if you're interested in doing anything more then occationally toggling pins on an arduino.

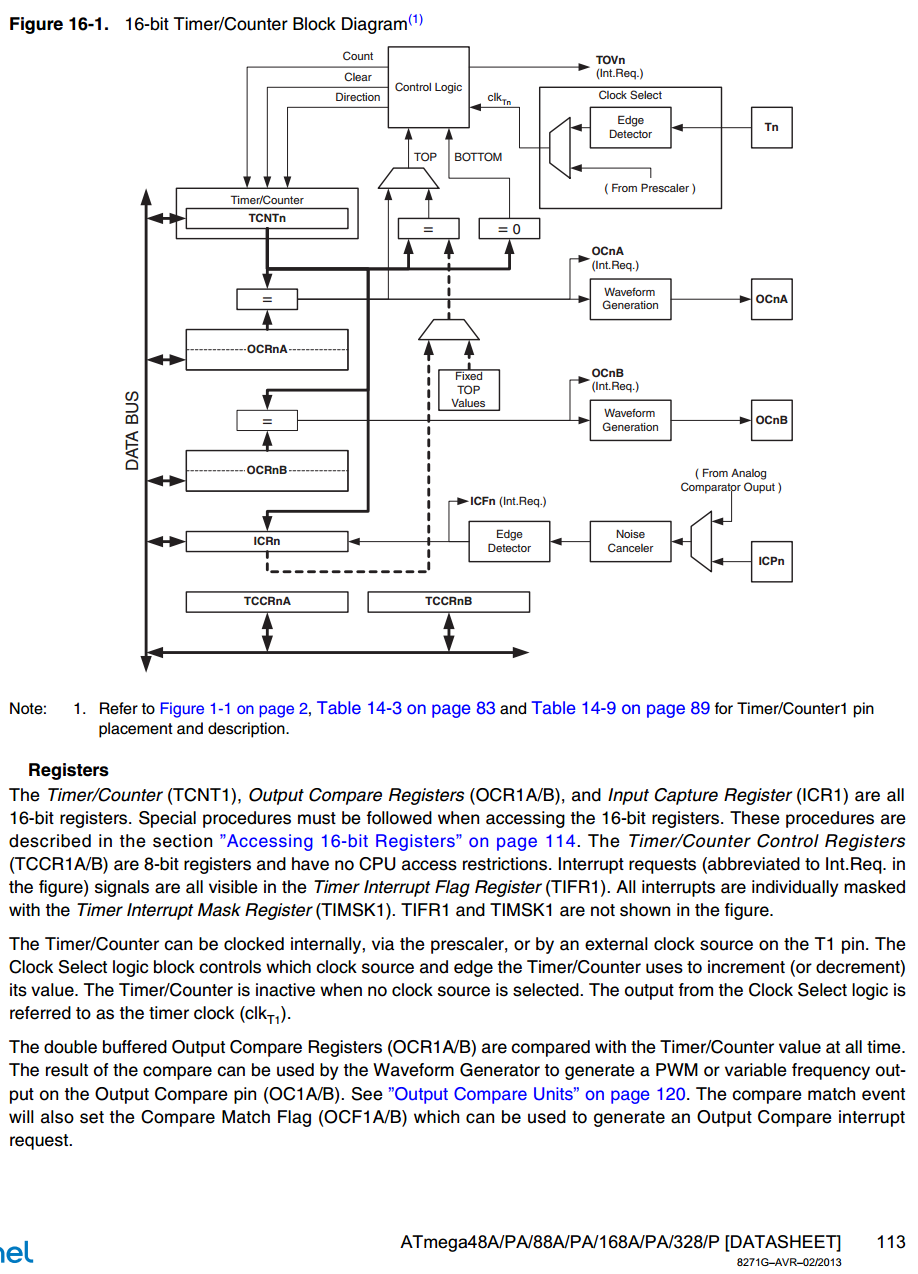

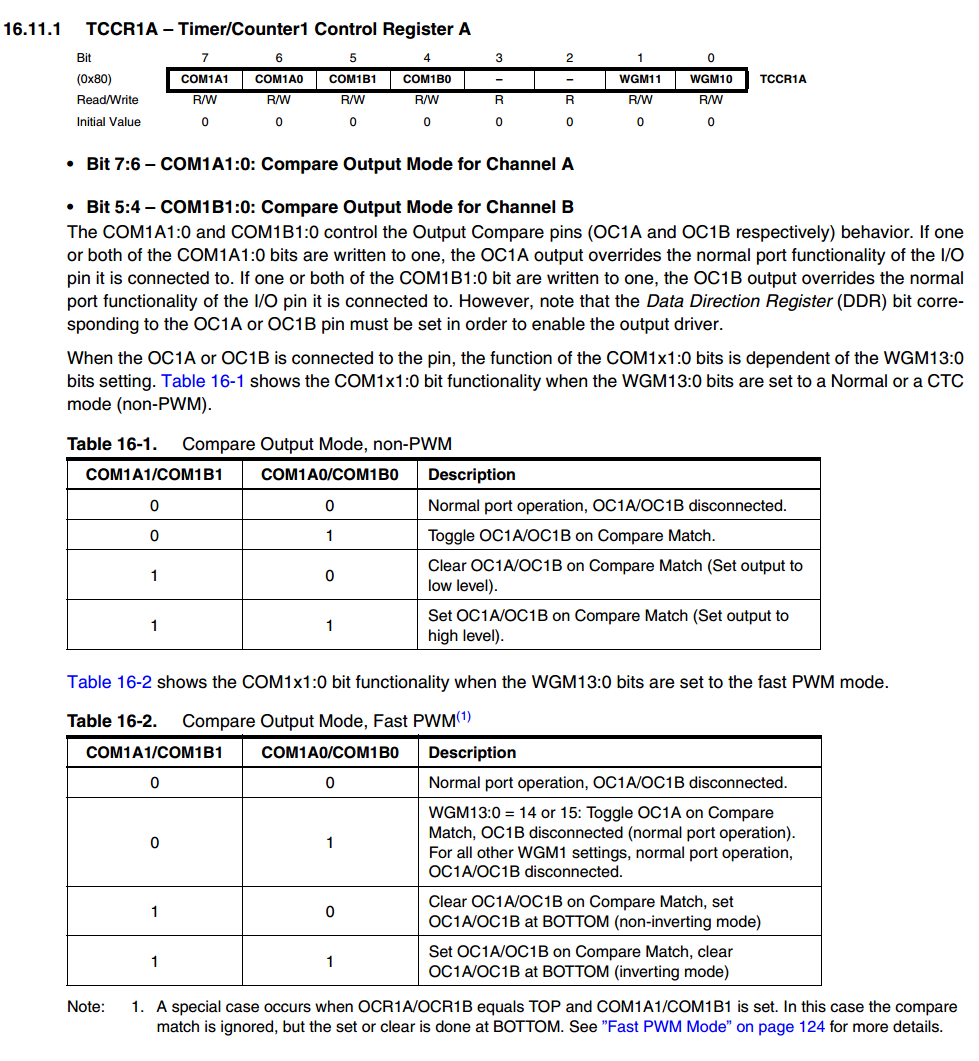

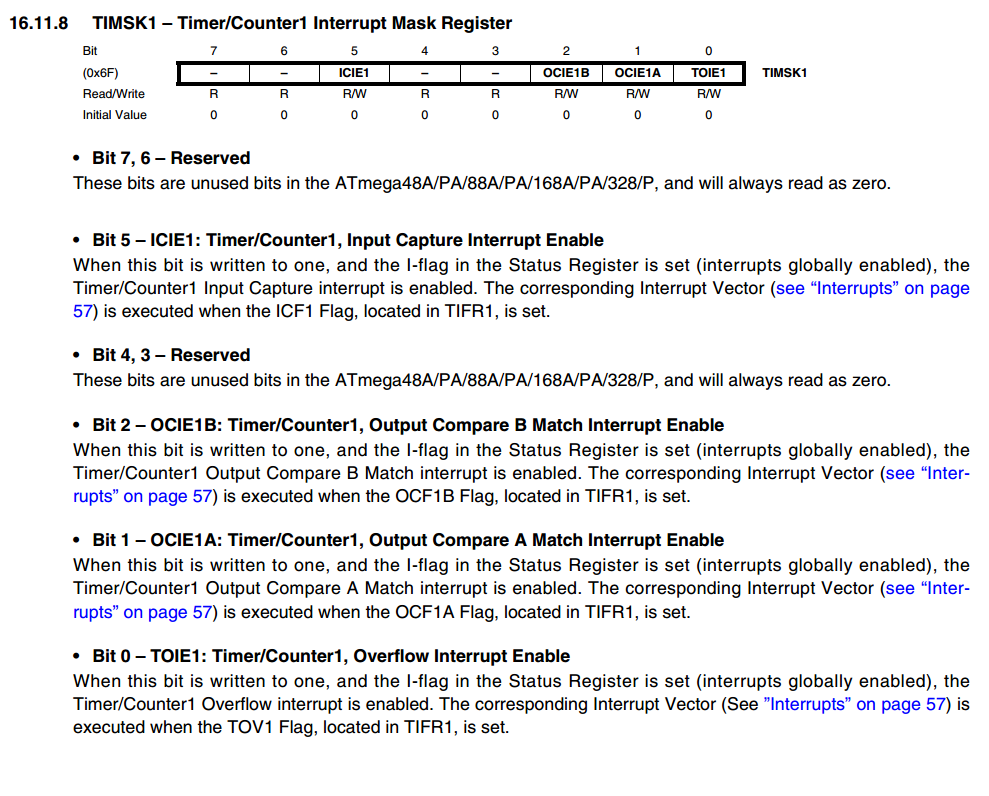

Select excerpts from the datasheet linked above:

So, for example, TIMSK1 |= (1 << TOIE1); sets the bit TOIE1 in TIMSK1. This is achieved by shifting binary 1 (0b00000001) to the left by TOIE1 bits, with TOIE1 being defined in a header file as 0. This is then bitwise ORed into the current value of TIMSK1, which effectively set this one bit high.

Looking at the documentation for bit 0 of TIMSK1, we can see it is described as

When this bit is written to one, and the I-flag in the Status Register is set (interrupts globally enabled), the Timer/Counter1 Overflow interrupt is enabled. The corresponding Interrupt Vector (See ”Interrupts” on page 57) is executed when the TOV1 Flag, located in TIFR1, is set.

All the other lines should be interpreted in the same manner.

Some notes:

You may also see things like TIMSK1 |= _BV(TOIE1);. _BV() is a commonly used macro originally from the AVR libc implementation. _BV(TOIE1) is functionally identical to (1 << TOIE1), with the benefit of better readability.

Also, you may also see lines such as: TIMSK1 &= ~(1 << TOIE1); or TIMSK1 &= ~_BV(TOIE1);. This has the opposite function of TIMSK1 |= _BV(TOIE1);, in that it unsets the bit TOIE1 in TIMSK1. This is achieved by taking the bit-mask produced by _BV(TOIE1), performing a bitwise NOT operation on it (~), and then ANDing TIMSK1 by this NOTed value (which is 0b11111110).

Note that in all these cases, the value of things like (1 << TOIE1) or _BV(TOIE1) are fully resolved at compile time, so they functionally reduce to a simple constant, and therefore take no execution time to compute at runtime.

Properly written code will generally have comments inline with the code that detail what the registers being assigned to do. Here is a fairly simple soft-SPI routine I wrote recently:

uint8_t transactByteADC(uint8_t outByte) { // Transfers one byte to the ADC, and receives one byte at the same time // does nothing with the chip-select // MSB first, data clocked on the rising edge uint8_t loopCnt; uint8_t retDat = 0; for (loopCnt = 0; loopCnt < 8; loopCnt++) { if (outByte & 0x80) // if current bit is high PORTC |= _BV(ADC_MOSI); // set data line else PORTC &= ~(_BV(ADC_MOSI)); // else unset it outByte <<= 1; // and shift the output data over for the next iteration retDat <<= 1; // shift over the data read back PORTC |= _BV(ADC_SCK); // Set the clock high if (PINC & _BV(ADC_MISO)) // sample the input line retDat |= 0x01; // and set the bit in the retval if the input is high PORTC &= ~(_BV(ADC_SCK)); // set clock low } return retDat; } PORTC is the register that controls the value of output pins within PORTC of the ATmega328P. PINC is the register where the input values of PORTC are available. Fundamentally, things like this are what happen internally when you use the digitalWrite or digitalRead functions. However, there is a look-up operation that converts the arduino "pin numbers" into actual hardware pin numbers, which takes somewhere in the realm of 50 clock cycles. As you can probably guess, if you're trying to go fast, wasting 50 clock cycles on an operation that should only require 1 is a bit ridiculous.

The above function probably takes somewhere in the realm of 100-200 clock cycles to transfer 8 bits. This entails 24 pin-writes, and 8 reads. This is many, many times faster then using the digital{stuff} functions.