Engineering Real-Time: Lessons Learned While Chasing Determinism

November 17, 2025

Story

In hard real-time systems, deadlines aren’t suggestions, they draw the line between working and failing. Every task must finish exactly when it should; even a tiny slip can ripple through and throw everything else off balance.

Building a database management system that reliably functions under such timing constraints required addressing a unique set of challenges. We had to rethink what performance actually means, think about timing and what happens when a timing slot is missed, and deal with deadlines and priorities — things most database developers never have to worry about.

This series walks through what we ran into along the way: the design hurdles, the false starts, and the ideas that finally stuck. Even though the story comes from database work, the lessons apply to almost any middleware that has to run predictably when time really matters.

Setting the Stage

In the database world, “real-time” is associated with speed, but hard real-time systems are defined by predictability. Tasks must be completed at specific deadlines, and failing to meet those deadlines violates the system’s correctness, even if the computed result is otherwise correct.

You can see this in something as ordinary as a lab analyzer: dosing reagents, moving samples, reading sensors, all on a strict schedule. A delay anywhere throws off the whole process. The same goes for an infusion pump that adjusts medication flow in real time. When a patient’s vitals change, the pump has to react now, not “soon.” You don’t get second chances in that kind of system. Whether it’s a medical device, an industrial controller, or avionics software running hundreds of timed tasks, the rule never changes: if timing isn’t predictable, nothing else really works.

Traditionally, real-time systems ran tight control loops, reading sensors and driving actuators on a fixed schedule. Yet today’s embedded systems are more data-driven. Control logic and data handling now run side by side, logging and filtering, often managed by a database, are no longer background chores but part of the real-time loop itself. If the data feeding a control path comes through non-real-time code, timing breaks down. Even perfect control logic can’t fix late or inconsistent data.

Real-time software relies on the underlying real-time operating system (RTOS) scheduling to keep tasks on time and prevent low-priority code from blocking critical work. But the operating system’s scheduling isn’t enough; the data side has to keep up, too. That’s where a real-time database comes in, keeping the data path deterministic and in sync with everything else.

How Real-Time Scheduling Works Inside a Database

Just like an RTOS schedules tasks to keep everything on time, a real-time database must schedule its own work — the transactions. Each transaction is a set of read and write operations that must complete together and, like RTOS tasks, compete for shared resources under deadlines. The transaction manager, the part of the database kernel that decides which transaction runs next, handles this. It acts as the database’s own scheduler.

Traditional transactions follow the ACID principles of atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability to keep data correct even if something fails. But classic schedulers, such as two-phase locking, weren’t built to guarantee when a transaction finishes. They ensure correctness, not timely completion. Real-time scheduling algorithms provide the transaction manager with mechanisms for making timing-aware decisions that preserve both correctness and predictability. A key challenge is ensuring that database-level scheduling cooperates with, rather than conflicts with, the underlying RTOS scheduler.

One of the best-known scheduling algorithms is Earliest Deadline First (EDF). The idea is simple: out of all the transactions ready to run, the one with the closest deadline goes first.

In a real-time database, implementing the EDF algorithm is part of the transaction manager’s job. Instead of looking at fairness or order of arrival, it looks at time. EDF is popular because it’s simple, light, and, under the right conditions, the best at keeping deadlines from being missed. It’s a classic algorithm, and for good reason.

In a real-time database, implementing the EDF algorithm is part of the transaction manager’s job. Instead of looking at fairness or order of arrival, it looks at time. EDF is popular because it’s simple, light, and, under the right conditions, the best at keeping deadlines from being missed. It’s a classic algorithm, and for good reason.

The database transaction usually executes in the context of some RTOS task. The RTOS decides which task, and therefore which transaction, gets the CPU. Inside that task, the database’s EDF scheduler picks which transaction runs next. EDF works best on single-core systems: if it’s possible for all transactions to meet their deadlines without blocking, EDF will find that schedule. Hard real-time systems rarely use multi-core hardware — single-core MCUs remain common because they’re easier to validate and keep predictable. Still, when multiple cores are available, EDF can be adapted in several ways. The usual approach is to pin each task and its transactions to a specific core and let that core run its own EDF schedule. This keeps timing consistent and avoids delays from transactions jumping between CPUs. For systems that value determinism over raw throughput, keeping transactions local to a core is usually the safest choice.

In practice, many systems use a modified version of EDF with static priorities to align better with the RTOS and the rest of the application. Each transaction has both a priority and a deadline. The priority groups transactions by importance, and within each group, they’re scheduled by standard EDF rules.

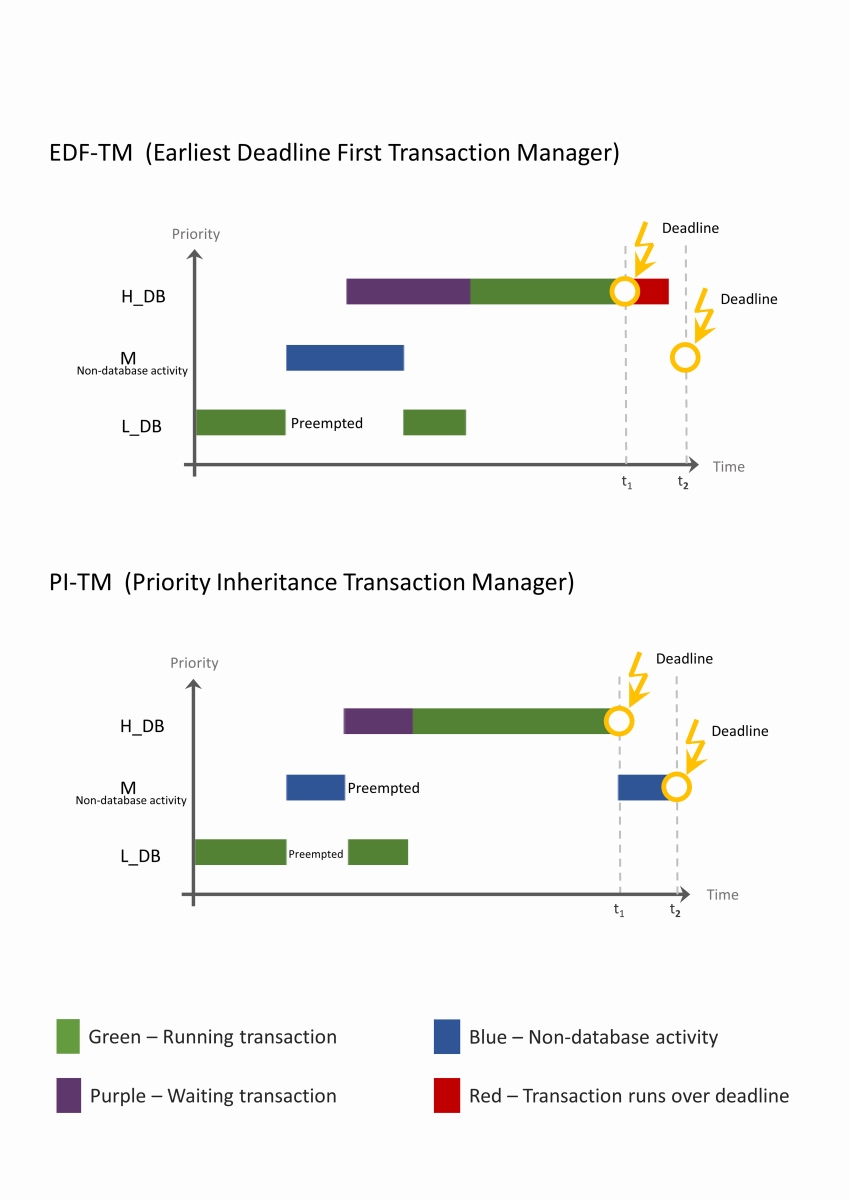

But EDF still has a weakness: priority inversion. That’s when a low-priority task, directly or indirectly, blocks a higher-priority one. Say a low-priority thread L starts a transaction. Then, a high-priority thread H becomes active (the database kernel has no control over RTOS scheduling) and tries to start its own database transaction that conflicts with L’s. Because L’s transaction is still open, H has to wait. Before L can finish, a medium-priority thread M wakes up. It doesn’t use the database but still preempts L, keeping it from finishing. Now L is stuck, H is waiting, and M, unintentionally blocks the highest-priority task. In EDF, that kind of situation can really throw the schedule off. The task with the earliest deadline (H) might end up missing it because of delays caused by “database” tasks with a later deadline L and the non-database M task.

To deal with this, another scheduling method was introduced, called Priority Inheritance (PI). In short, if a low-priority thread holds a resource that a high-priority thread needs, it temporarily inherits the higher priority. Once it’s done, for example, after finishing its transaction, its original priority is restored. In our example, thread M wouldn’t be able to preempt L, because L’s priority would be temporarily raised to match H’s. That lets L finish its transaction and frees H to continue.

From a practical standpoint, the choice between PI and EDF transaction managers depends on the system’s workload. The PI Transaction Manager fits best in systems that mix database work with CPU-heavy tasks that don’t touch the database. In those cases, priority inversion can become a real issue. The EDF manager coordinates locking only among database threads. When a database thread is blocked, it simply yields the CPU and waits, but threads that run outside the database keep going. If they preempt a lower-priority thread holding a database lock, priority inversion can happen.

The EDF Transaction Manager, on the other hand, is a better fit for database-driven systems, where most of the activity involves database operations. It doesn’t directly schedule system tasks, but it works with the operating system’s synchronization mechanisms to put blocked threads into a WAIT state, take them out of scheduling, and make sure transactions run according to the priorities set by the transaction manager.

How We Know When “On Time” Is Actually On Time

Scheduling by itself is only the first step. An algorithm like EDF determines the order in which transactions are executed, but it doesn’t guarantee that a transaction that’s about to be late will be immediately stopped. Continuing to run such a transaction isn’t just pointless, it’s harmful. Its result doesn’t matter anymore, and worse, it holds resources that other transactions need. It may even block the rest of the system, setting off a chain reaction of missed deadlines. That’s why the transaction manager must also include a timing control mechanism to detect and abort transactions before they exceed their deadlines.

In the next segment of this series, we will examine how timing is measured, monitored, and verified inside the database kernel, and how developers can apply the same techniques in other hard real-time middleware to make sure that “on time” is actually on time.

For more information, visit: www.mcobject.com/