Simple answer: thisThis is a constant current sink. It isn't (to my knowledge) named after its inventor, so sadly there seems to be no moniker that that distinguishes it from other designs. Another user (Hearth) suggested "two-transistor current sink", but your own term "mutual-feedback transistors" could fit the bill too. Perhaps it will catch on.

ForIt may also be referred to as a current limiter (as might any constant current sink/source) because it cannot force current through the detailsload. It cannot prevent a load from passing less current (in magnitude) than the intended amount, read onbut it will certainly impose an upper constraint.

Some might call it a current sourcesource, rather than a sink, because people tend to call anything that regulates current a "current source", regardless of whether it sources or sinks, but in thisstrictly speaking your circuit is a sink.

That's the simple answer, to your "simple question", but for more details, read on.

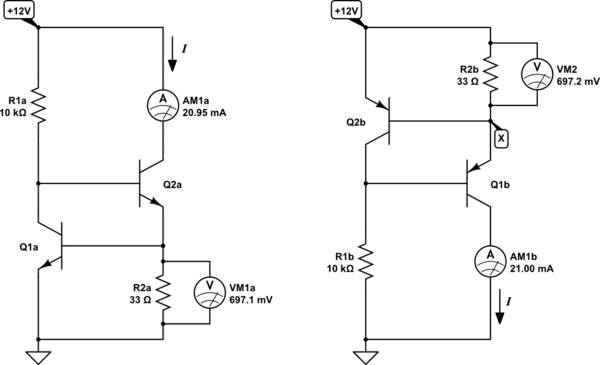

In your circuit current is being "sunk" to ground through the 10Ω load. If it were made using PNP transistors instead, then it would perform the exact same function, except it becomes a constant current source in the true sense, shown below right:

simulate this circuit – Schematic created using CircuitLab

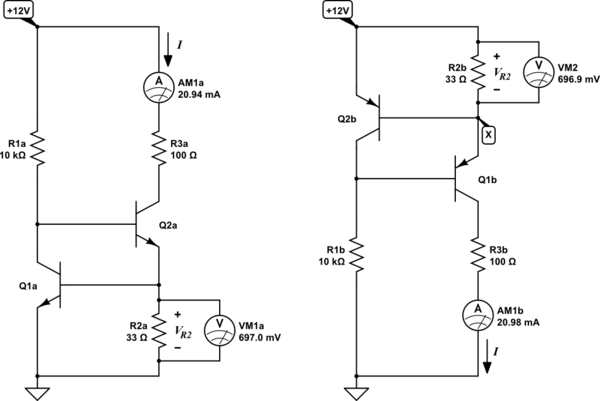

The ammeters are measuring that current \$I\$, which is about 21mA in both cases. We can even insert an extra resistance in that current path (R3 below), and \$I\$ won't change (much), hence my use of the the term "constant":

Q2's state is controlled by Q1; If Q1 were to switch off, Q2's base would rise in potential, switching Q2 more on, and vice versa. Q1's state is controlled by the voltage \$V_{R2}\$ across R2, shown on the voltmeters. If \$V_{R2}\$ is more than 0.7V, then Q1 would switch on, switching Q2 off, and if it were less than 0.7V, then Q1 would switch off, turning on Q2.

\$V_{R2}\$ is determined (mostly) by current \$I\$ flowing through R2, by Ohm's law. If you've followed so far, then you can see that when \$I\$ is too much, causing \$V_{R2} > 0.7V\$, then Q2 switches off, reducing \$I\$. Conversely, if \$I\$ is too little, so that \$V_{R2} < 0.7V\$, then Q2 switches on, increasing \$I\$.

In other words, any perturbation of \$I\$ causes the system to react to oppose that perturbation, a kind of negative feedback. The result is that the system settles in the equilibrium condition where \$I\$ is exactly the right amount to produce \$V_{R2}=0.7V\$.

Therefore (approximately, because we haven't accounted for transistor base currents, which are small but non-zero) by Ohm's law:

$$ I \approx \frac{0.7V}{R_2} $$

In the above examples this is:

$$ I \approx \frac{0.7V}{33\Omega} \approx 21mA $$