G. C. Cawley and G. J. Janacek, On allometric equations for predicting body mass of dinosaurs, Journal of Zoology, vol. 280, no. 4, pp. 355-361, 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00665.x (preprint)

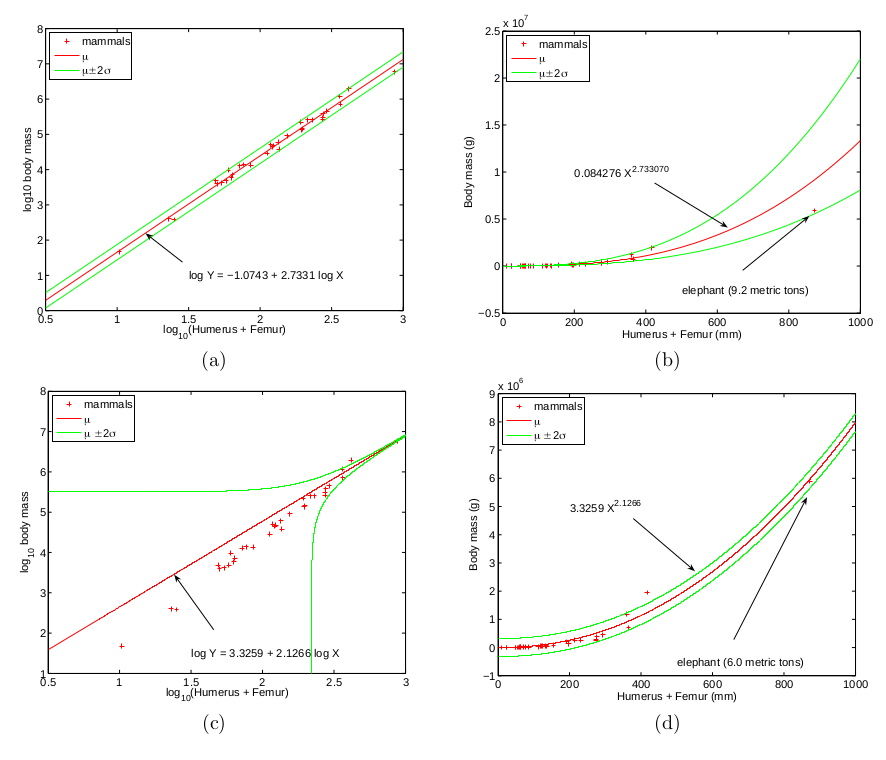

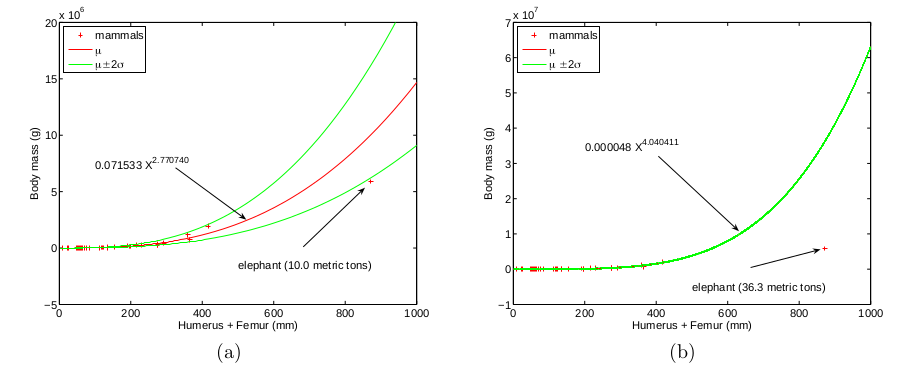

This example shows some advantages of log transformation in allometry, (a) and (b) show the long bone circumferences and body masses of 33 mammals (used to predict quadrapedal dinosaur body masses), plotted on log-log axes and on linear axes. This shows that a linear model on log-log transformed data is a very reasonable model. (c) and (d) show the power law model of Packard et al. which was fitted using least squares without the log transformation, which looks O.K. (ish) on linear axes, but of you back-transform the model to log-log axes, then it is very clearly biased, with the body masses of smaller mammals being consistently over-predicted. The predictive error bars of the model also imply that it is possible for some smaller mammals to have a negative body mass.

The conventional allometric model is just about able to explain the observed body mass of an elephant (it is an outlier among mammals - it has very strong bones for it's body mass, perhaps because it is a very active animal). The model fitted on linear axes on the other hand has the elephant lying many standard deviations away from the predicted value. The conventional model predicts the elephant as having a body mass of about 10 tons (4 would be a more accurate estimate). The Packard et al model though, predicts the mass to be 36 tons, which is wildly wrong (and the estimates for the body masses of dinosaurs are also much higher - the estimated mass of Apatosaurus louisiae rises from 18.2 tons to 302 tons, which is completely implausible). The reason for this is the next most heavy mammal is the hippo, which has a relatively high body mass for its bone circumference.