Digital signals have two positions: on or off, interpreted in shorthand as 1 or 0. Analog signals, on the other hand, can be on, off, half-way, two-thirds the way to on, and an infinite number of positions between 0 and 1 either approaching 1 or descending down to zero. The two are handled very differently in electronics, but very often must work together (that’s when we call it “mixed signal electronics.”) Sometimes we have to take an analog (real world) input signal (e.g., temperature) into a microcontroller (which only understands digital). Often engineers will translate that analog input into digital input for the microcontroller (MCU) by using an analog-to-digital converter. But what about outputs?

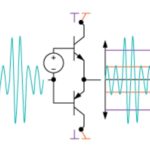

PWM is a way to control analog devices with a digital output. Another way to put it is that you can output a modulating signal from a digital device such as an MCU to drive an analog device. It’s one of the primary means by which MCUs drive analog devices like variable-speed motors, dimmable lights, actuators, and speakers. PWM is not true analog output, however. PWM “fakes” an analog-like result by applying power in pulses, or short bursts of regulated voltage.

An example would be to apply full voltage to a motor or lamp for fractions of a second or pulse the voltage to the motor at intervals that made the motor or lamp do what you wanted it to do. In reality, the voltage is being applied and then removed many times in an interval, but what you experience is an analog-like response. If you have ever jogged a box fan by applying power intermittently, you will experience a PWM response. The fan and its motor do not stop instantly due to inertia, and so by the time you re-apply power it has only slowed a bit.

Therefore, you do not experience an abrupt stop in power if a motor is driven by PWM. The length of time that a pulse is in a given state (high/low) is the “width” of a pulse wave.

A device that is driven by PWM ends up behaving like the average of the pulses. The average voltage level can be a steady voltage or a moving target (dynamic/changing over time). To simplify the example, let’s assume that your PWM-driven fan has a high-level voltage of 24 volts. If the pulse is driven high 50% of the time, we call this a 50% duty cycle. The term duty cycle is used elsewhere in electronics, but in every case duty cycle is a comparison of “on” versus “off.”

Going back to our fan motor example, if we know that the high voltage is 24, the low is 0v, and the duty cycle is 50%, then we can determine the average voltage by multiplying the duty cycle by the pulse’s high level. If you want the motor to go faster, you can drive the PWM output to a higher duty cycle. The higher the frequency of high pulses, the higher the average voltage and the faster the fan motor will spin. IF you were making your own PWM output by plugging the fan in and out of a socket at equal intervals of 1 second in the socket, 1 second out, then you are acting like a digital output that’s driving the fan at a steady average of 12V.

The analogy comes in when you increase the frequency of plugging in and out of the socket so that you only have it in the socket ½ a second and out of the socket an equal ½ second. At this point, your duty cycle is still 50%, but you have increased the number of cycles per second to two. In electronics, we would identify frequency as cycles per second, or Hertz (Hz.) You have increased the speed of the fan. That ½ second is the width of the pulse you are making.

You might have gathered by now that PWM, duty cycle, and frequency are interrelated. We use duty cycle and frequency to describe the PWM, and we often talk about frequency in reference to speed. For example, a variable frequency drive motor produces a response like analog device in the real world. The separate pulses that the VFD motor gets are not discernable to us; as far as we can see, the pulses are so fast (usually somewhere in the milliseconds) that by real world standards it just seems like a motor ramping up.

If you take the duty cycle and multiply it by the high voltage level (which is a digital “on” or “1” state as far as the MCU is concerned), you will get the average voltage level that the motor is seeing at that moment.

Duty Cycle x High Voltage Level = Average Voltage

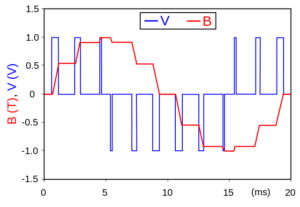

Now put the word “instantaneous” in there and you get the idea that things are dynamically changing…which looks more analog (see Figure 2):

Instantaneous Duty Cycle x High Voltage Level = Instantaneous Average Voltage

The duty cycle can change to affect the average voltage that the motor experiences. The frequency of the cycles can increase. The pulse can even be increased in length. These can all happen together, too, but in general, it’s easier to think of as either duty cycle increasing or frequency increases to increase the speed of the motor. (Pulse width is directly related to duty cycle, so if you decide to increase the width of a pulse, you are just altering the duty cycle.)

The only thing that hasn’t changed in all of this is the high voltage level, because “on” is always the same for the digital output; merely flicking the output on and off at varying speeds and for varying lengths of time is how you get pulse width modulation to fake an analog output. MCUs are digital. An example of something that can create a true analog output would be a transducer (something that directly translates physical phenomenon to an analog signal). But transducers are another analog discussion.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.