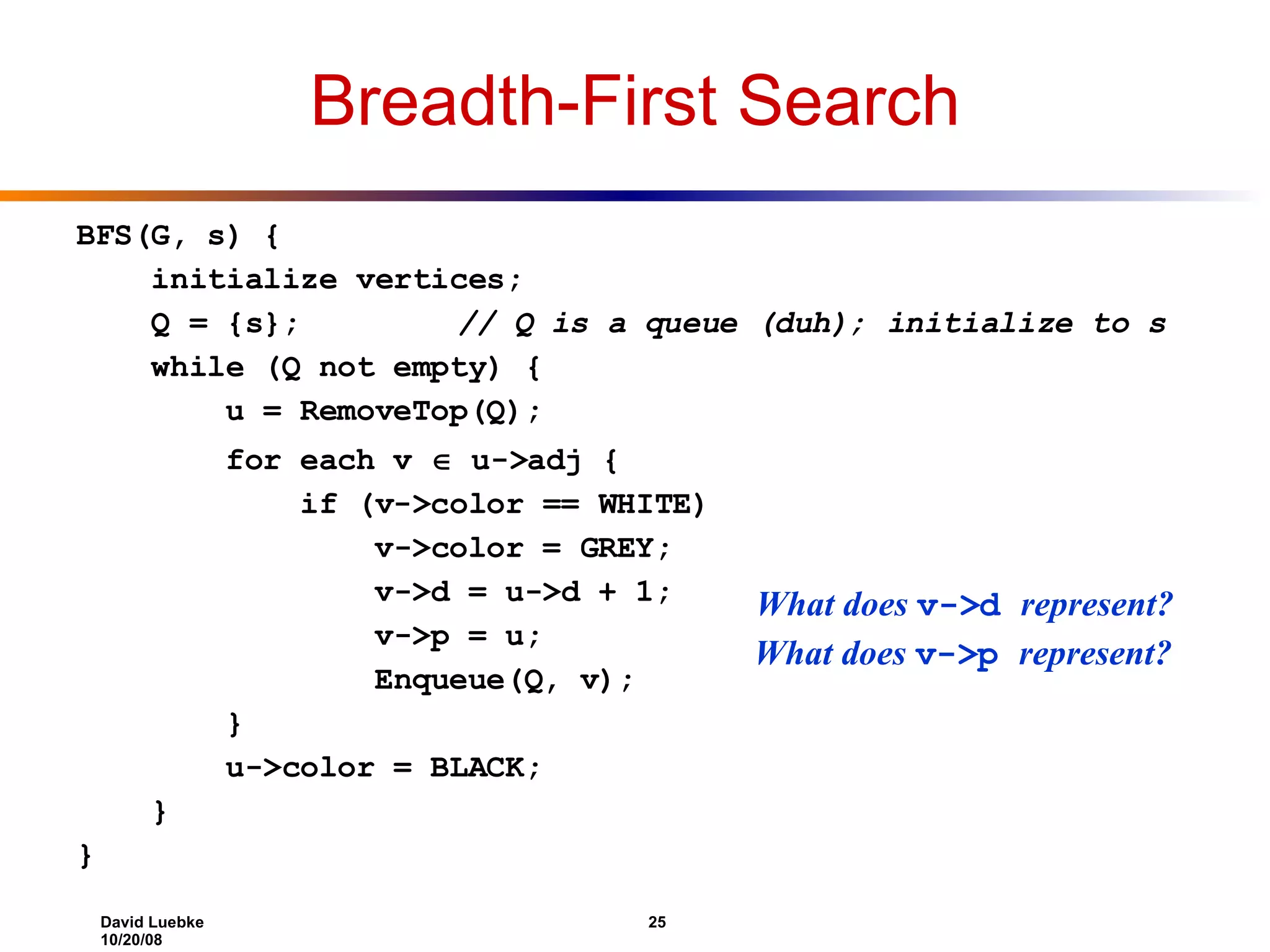

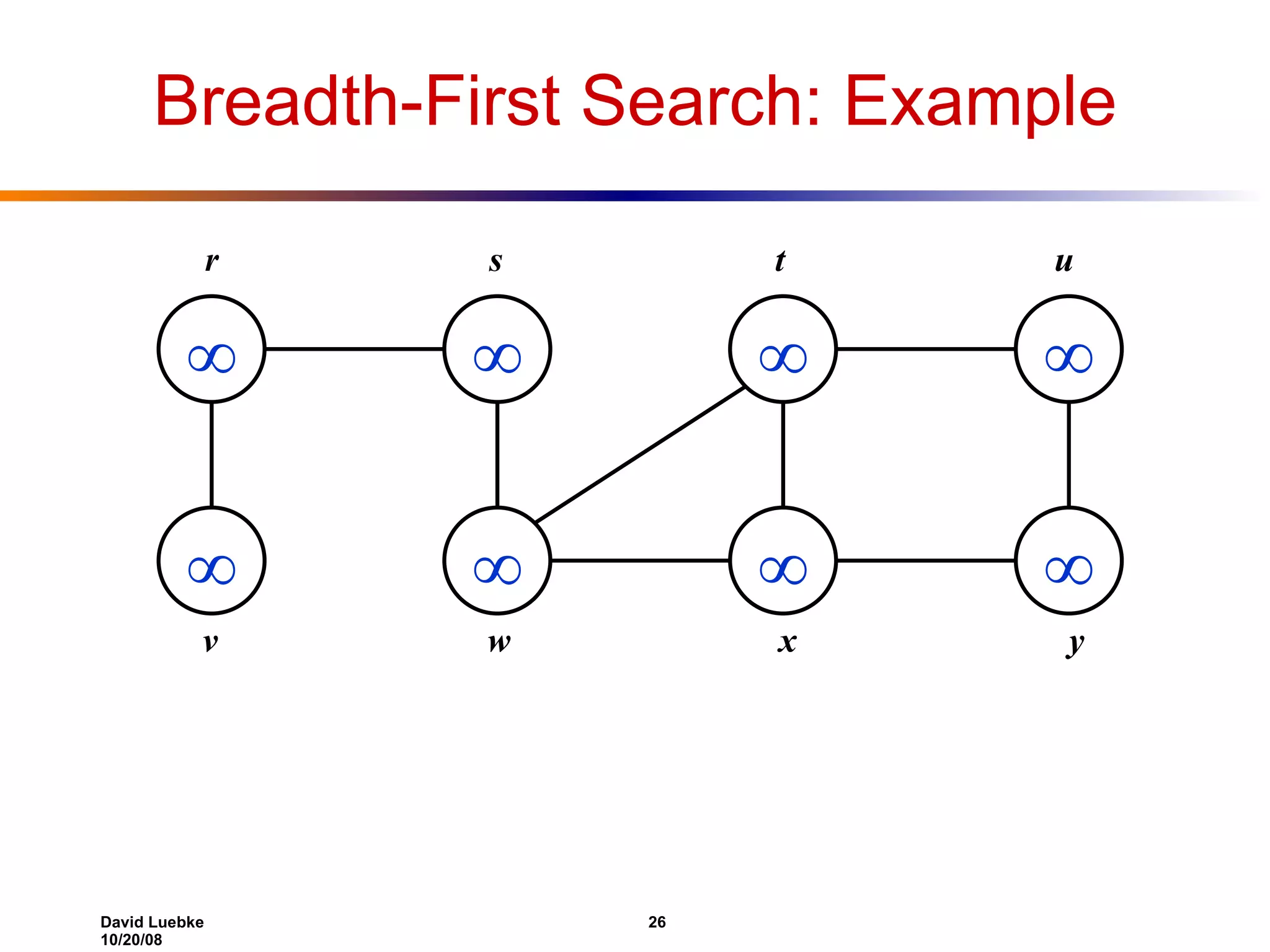

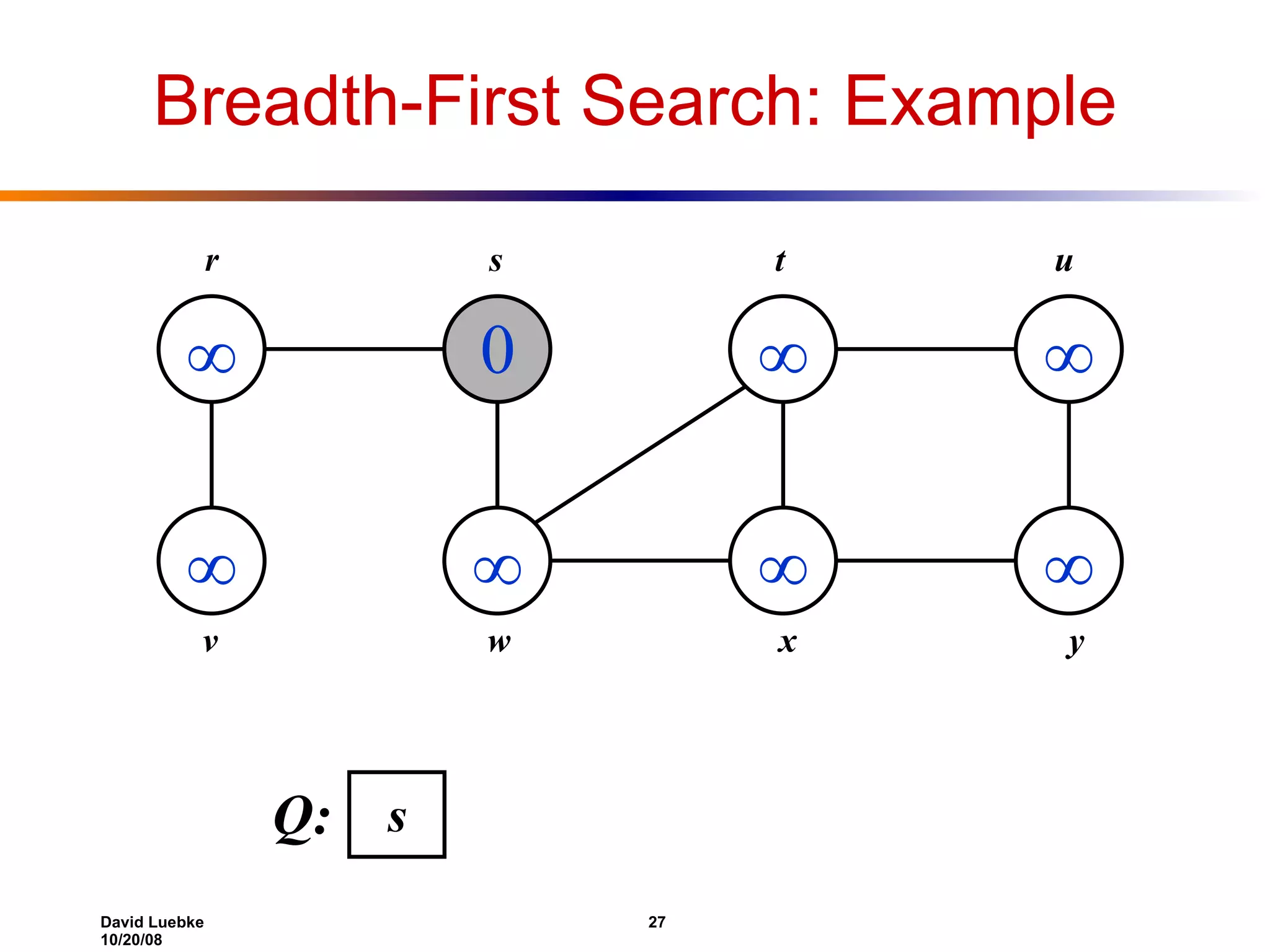

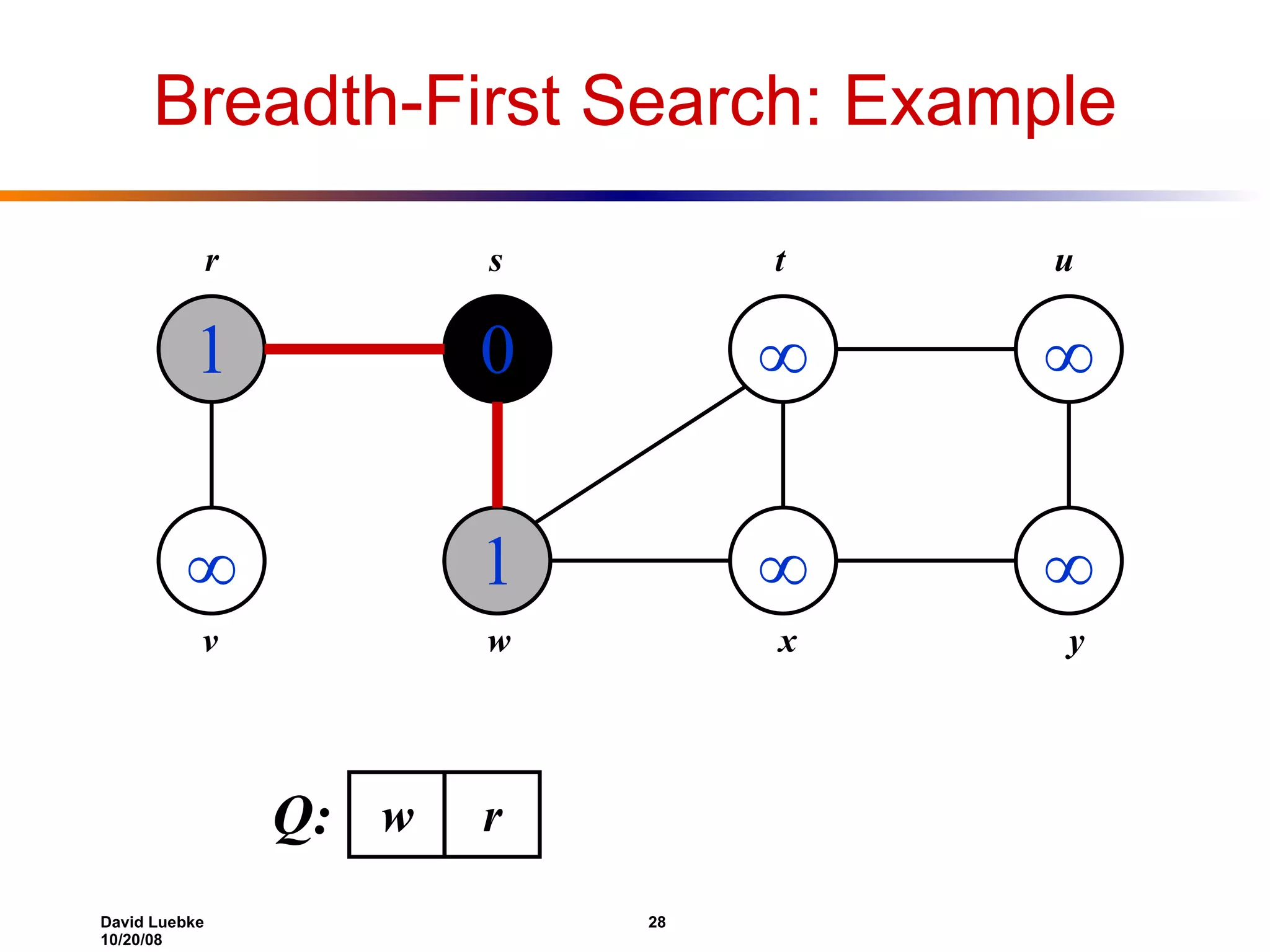

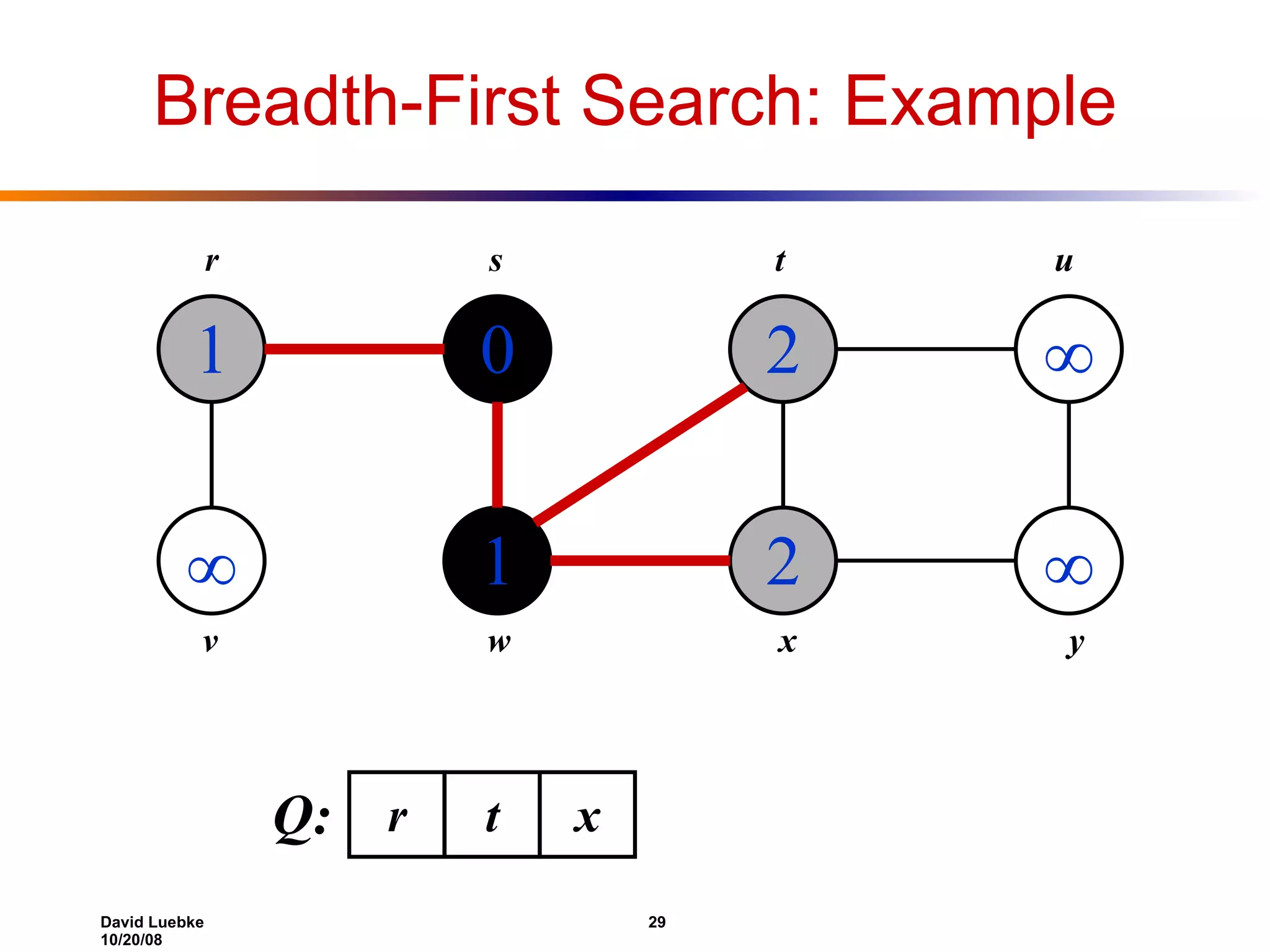

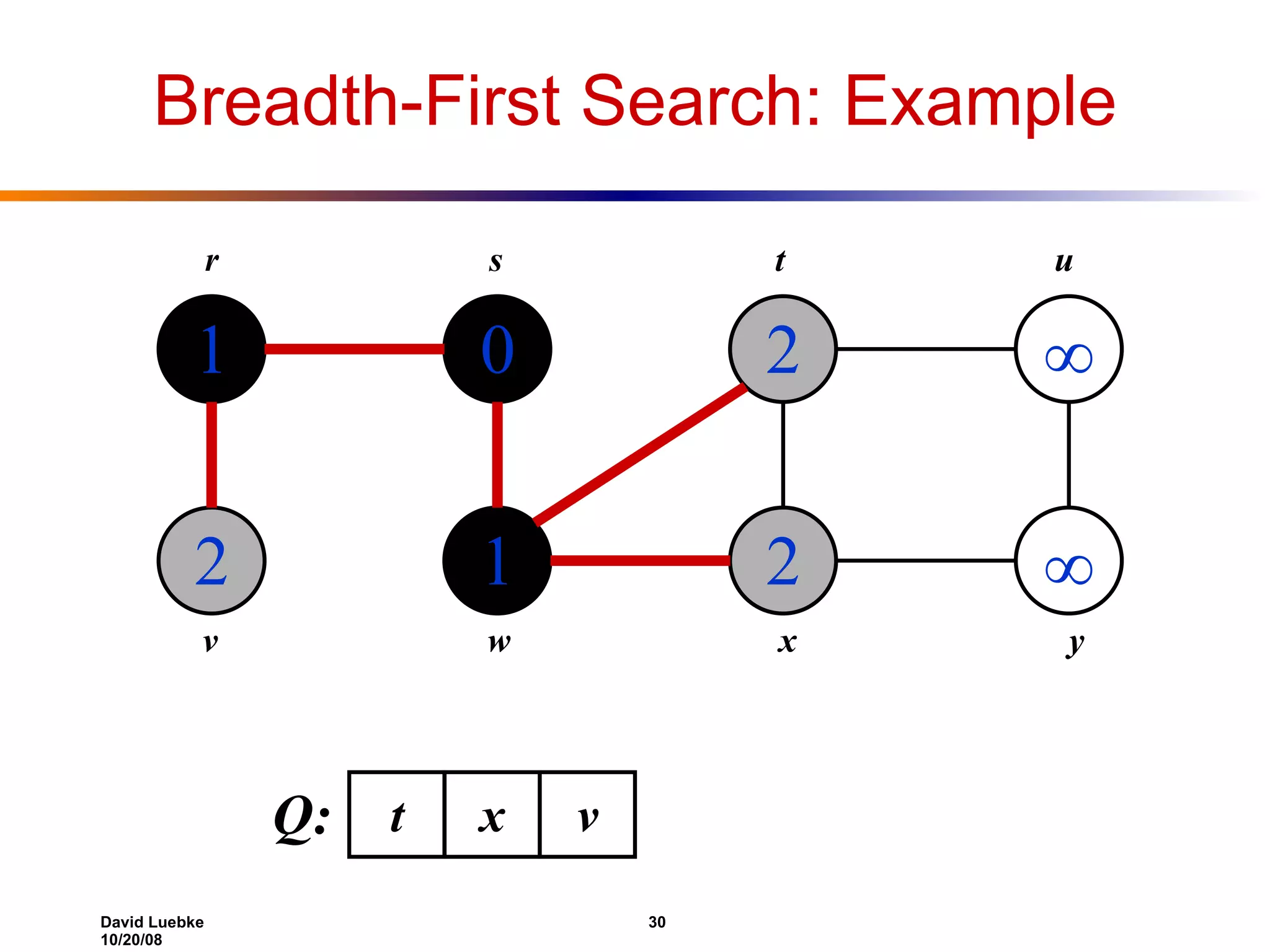

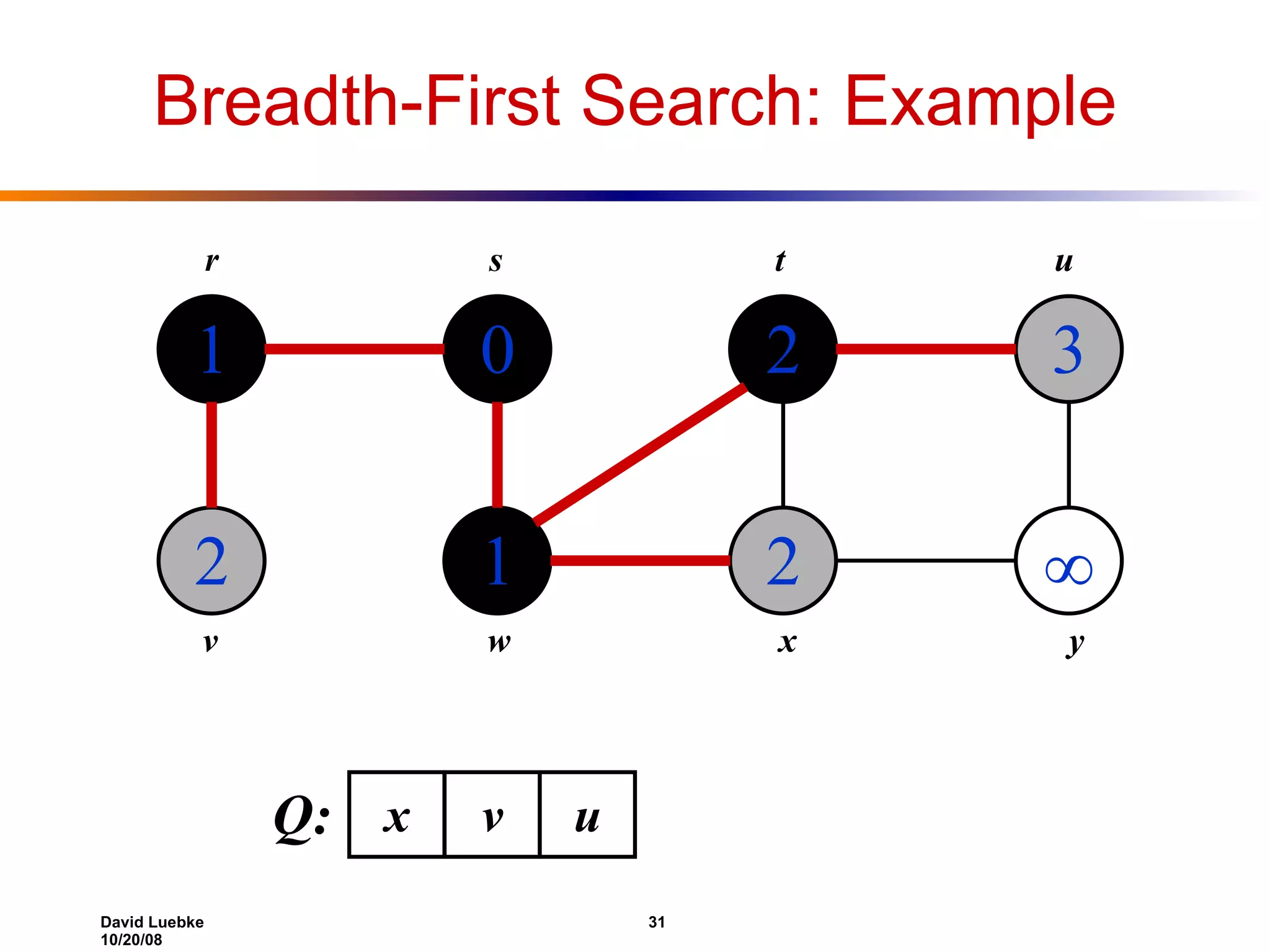

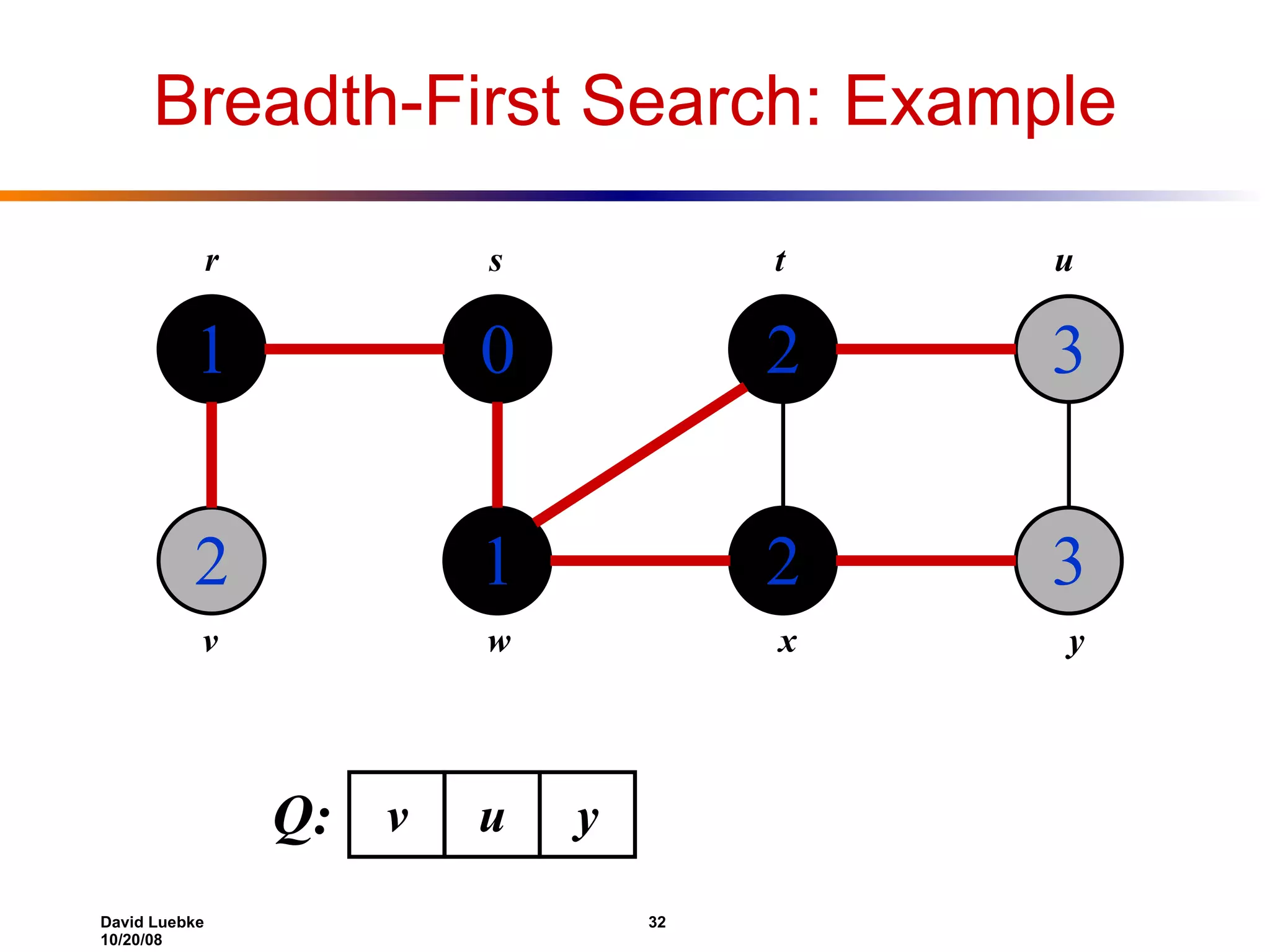

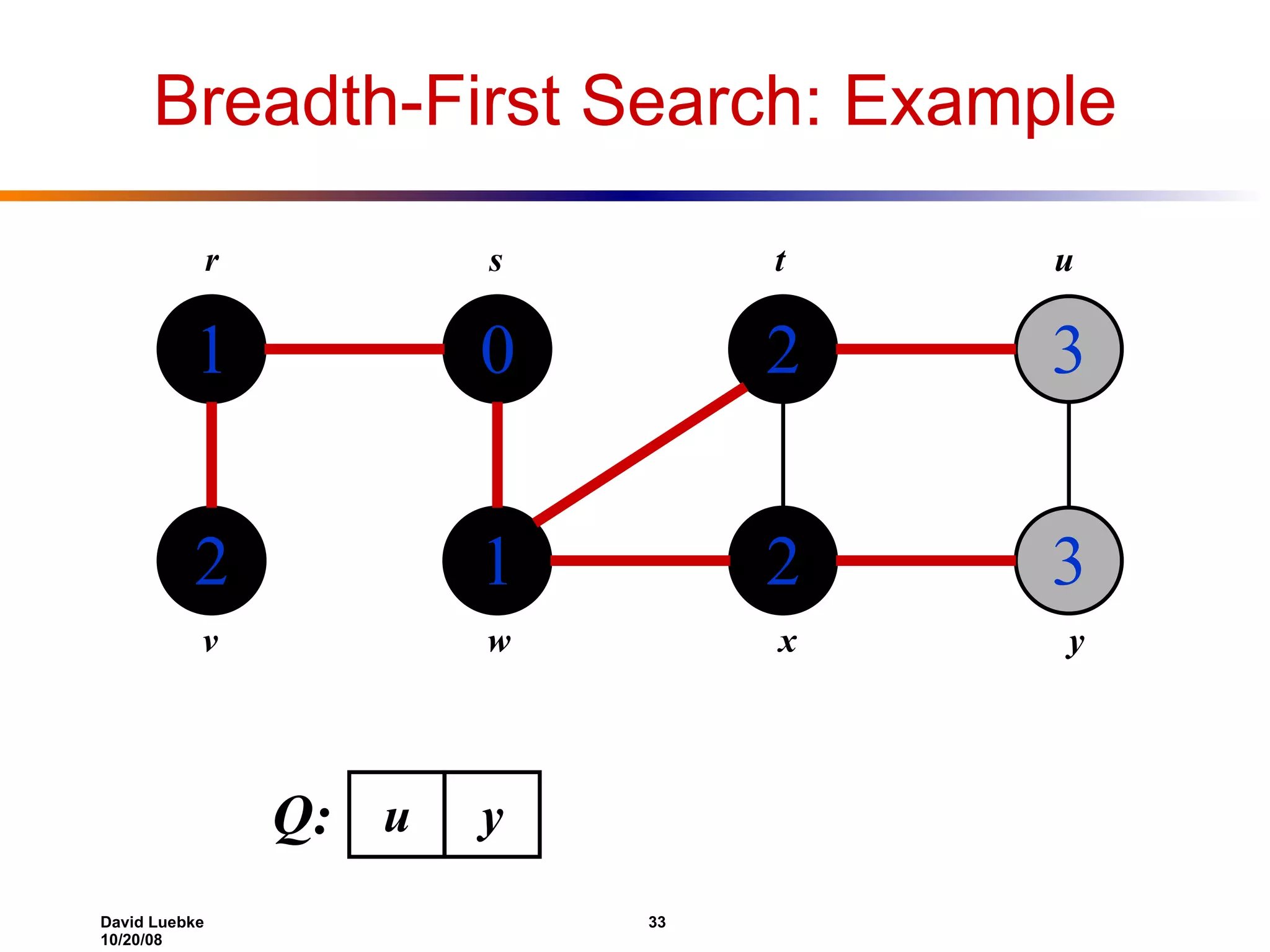

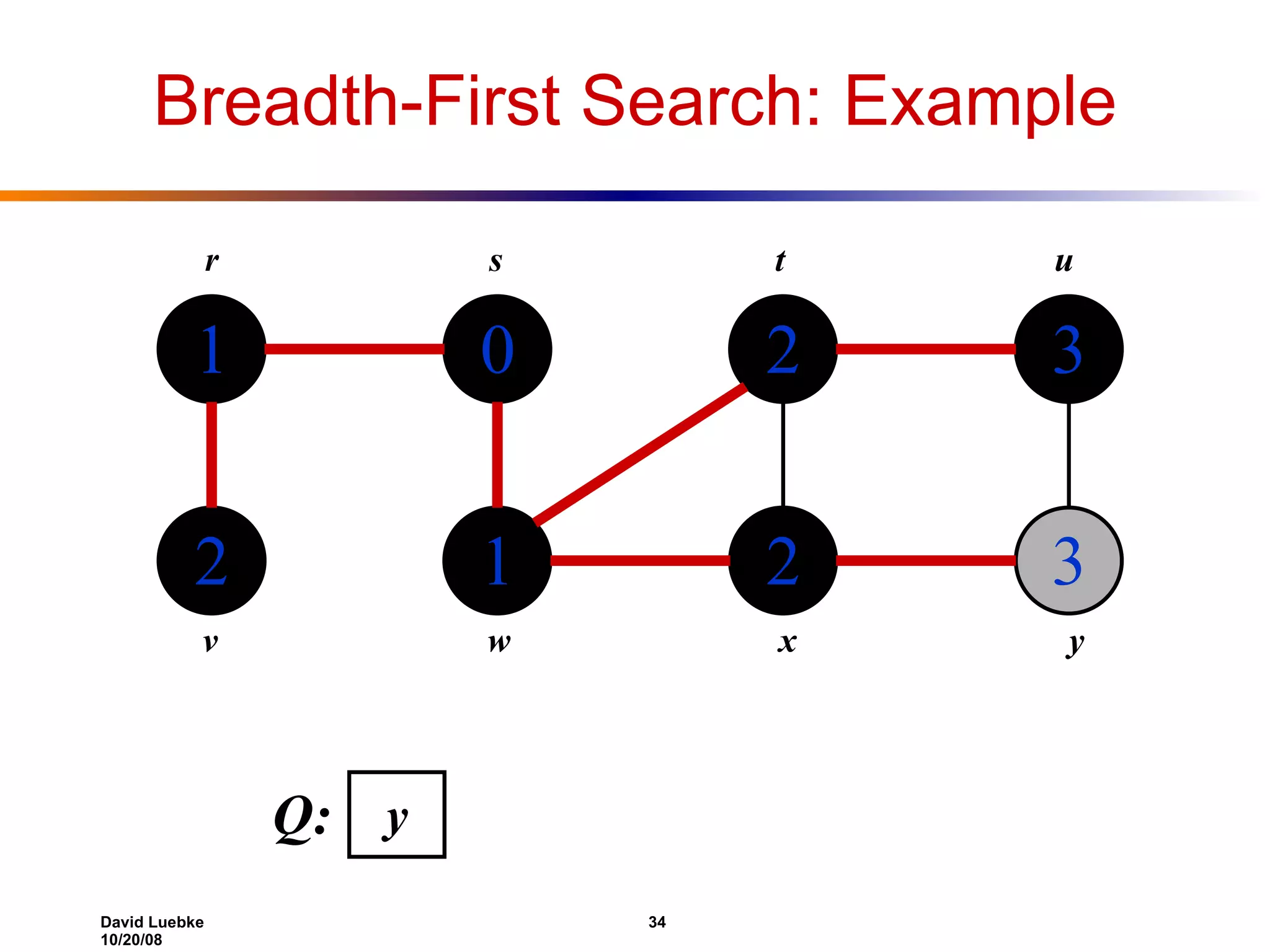

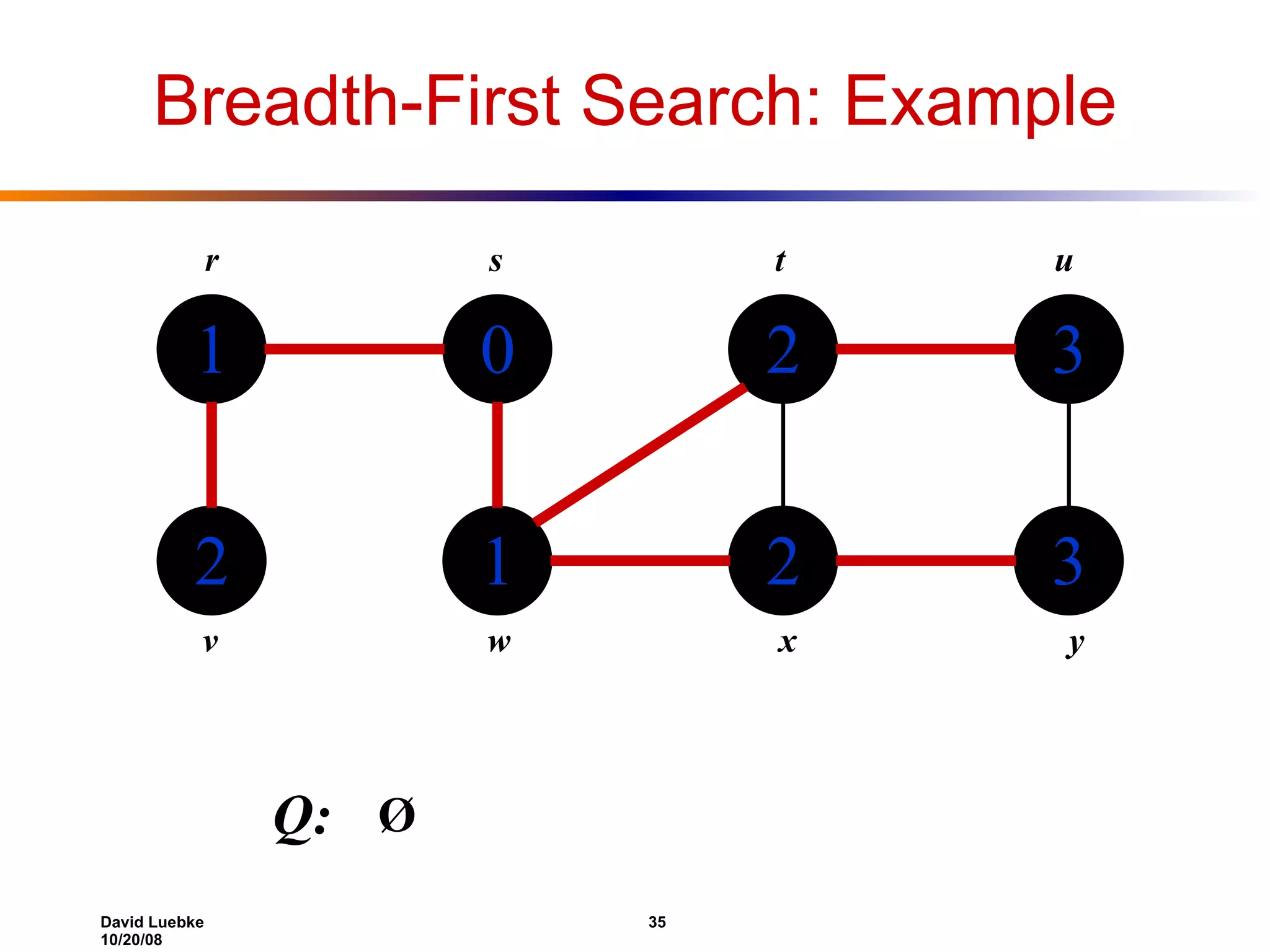

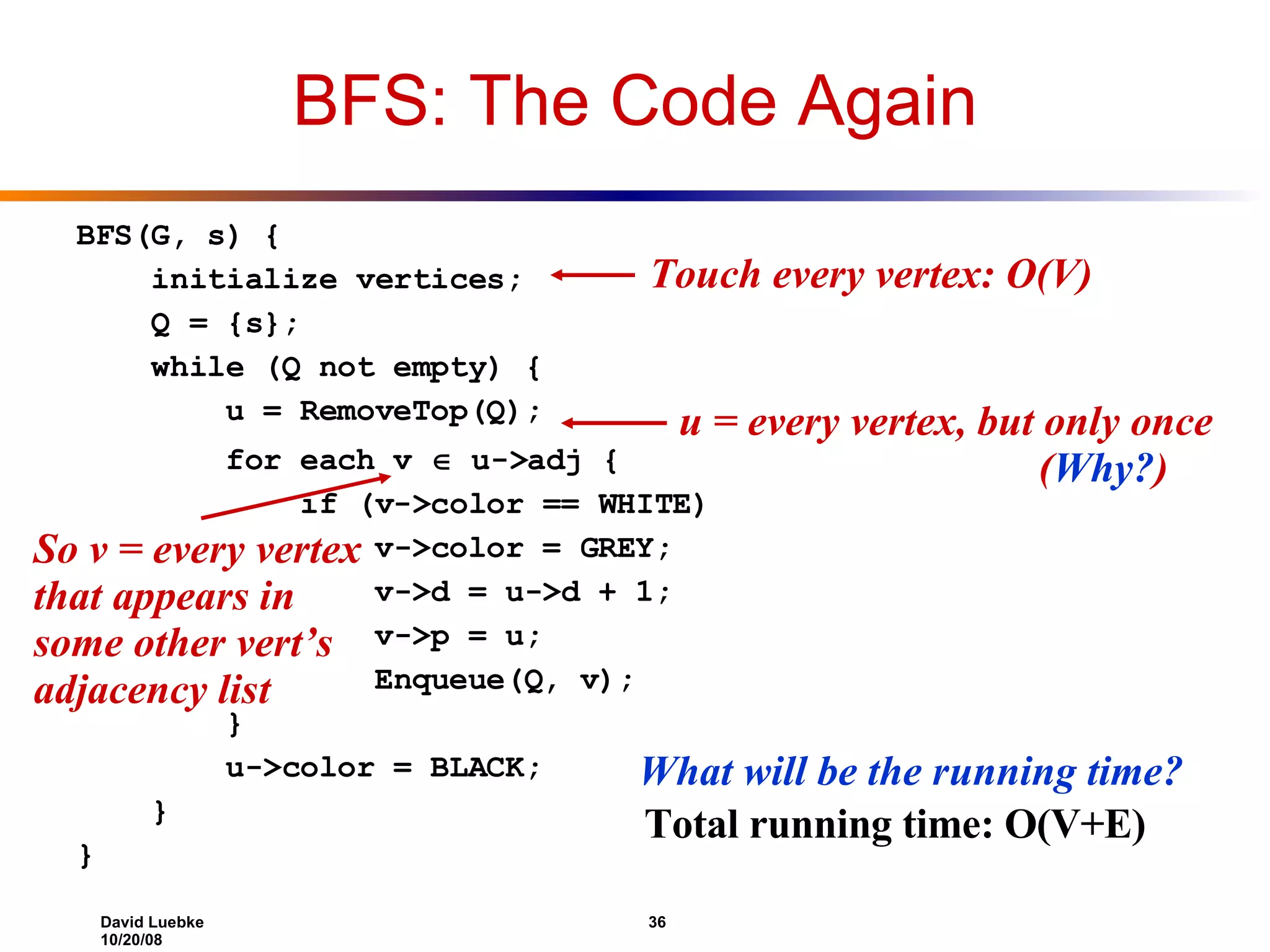

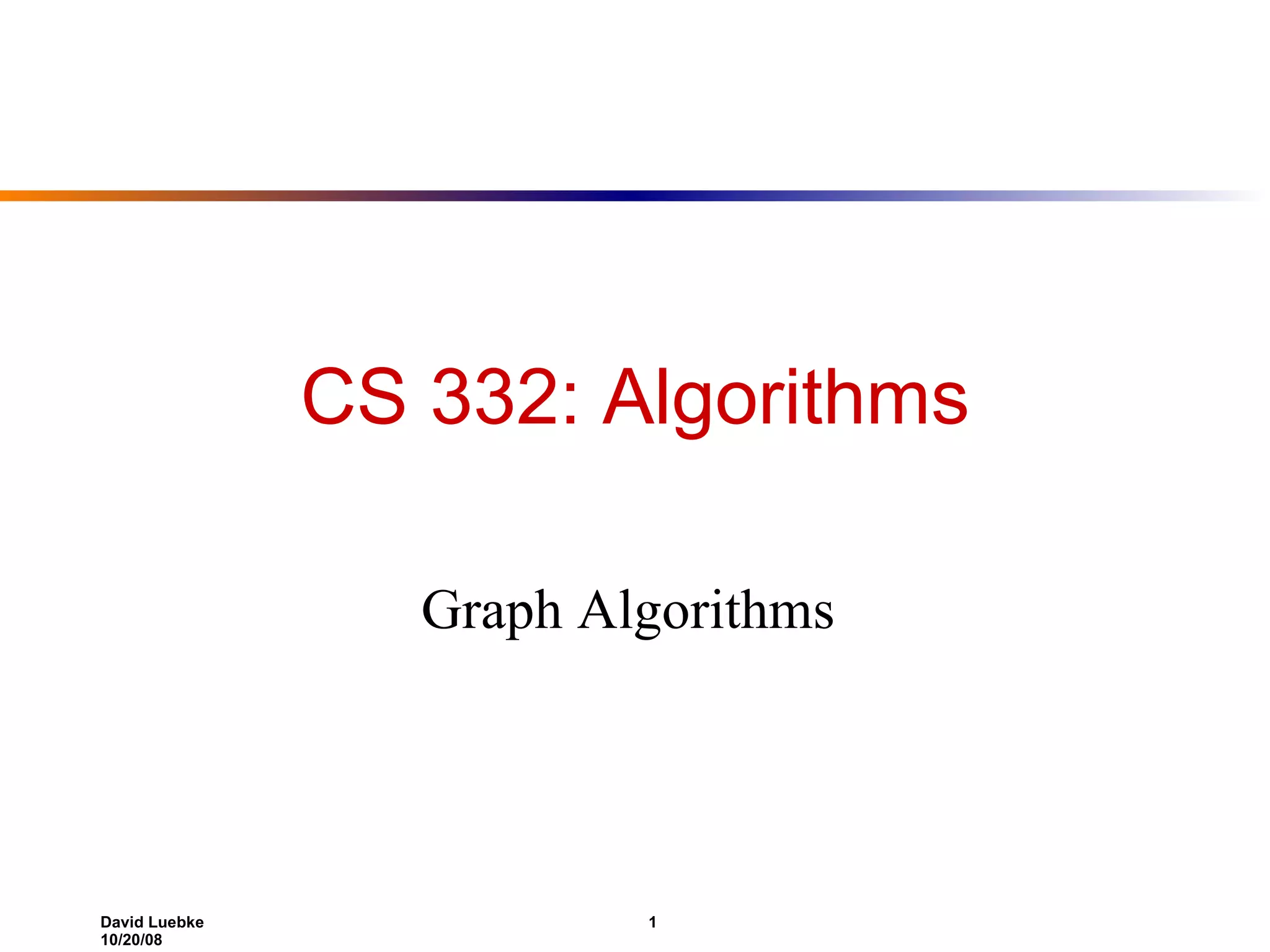

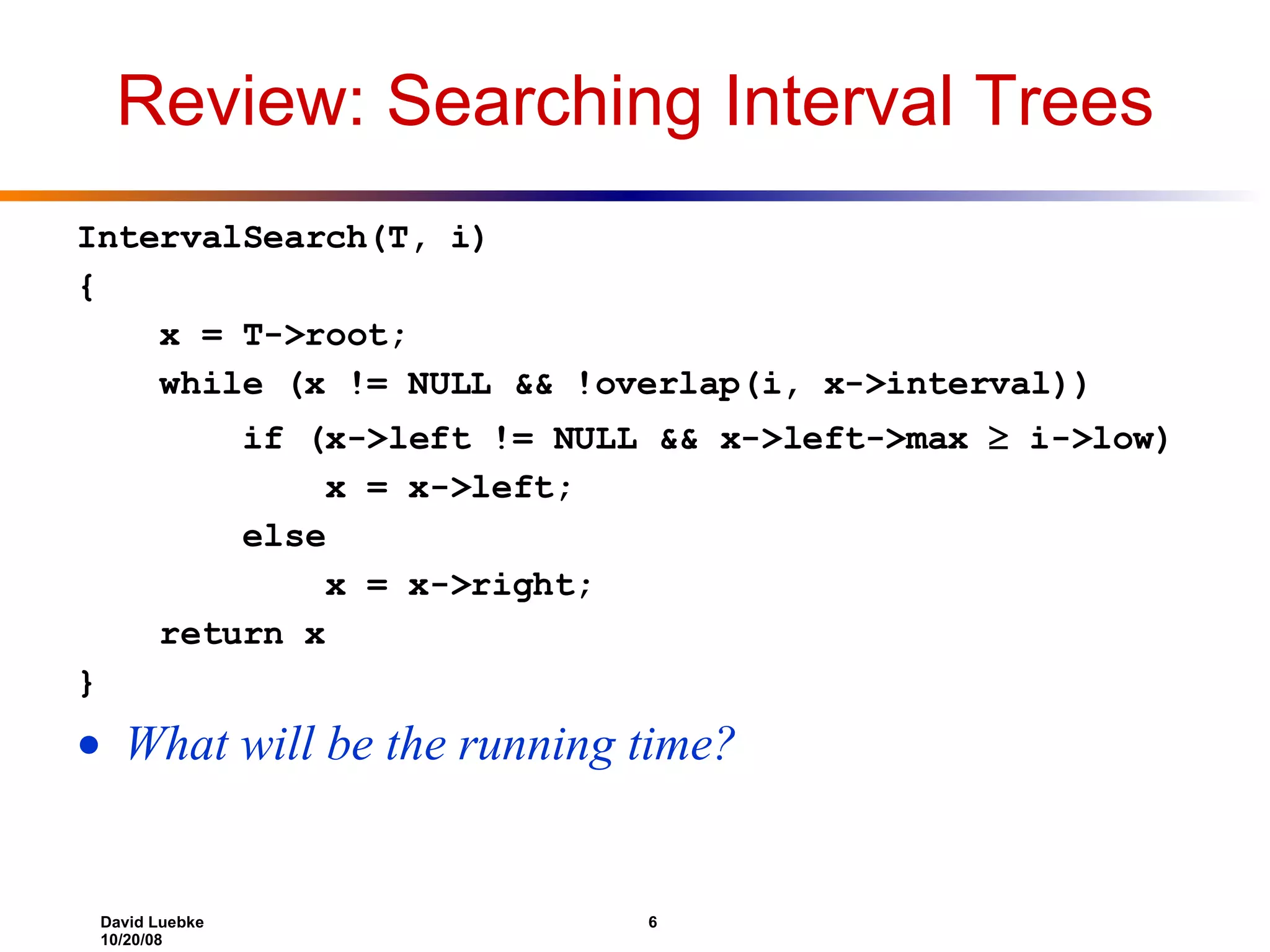

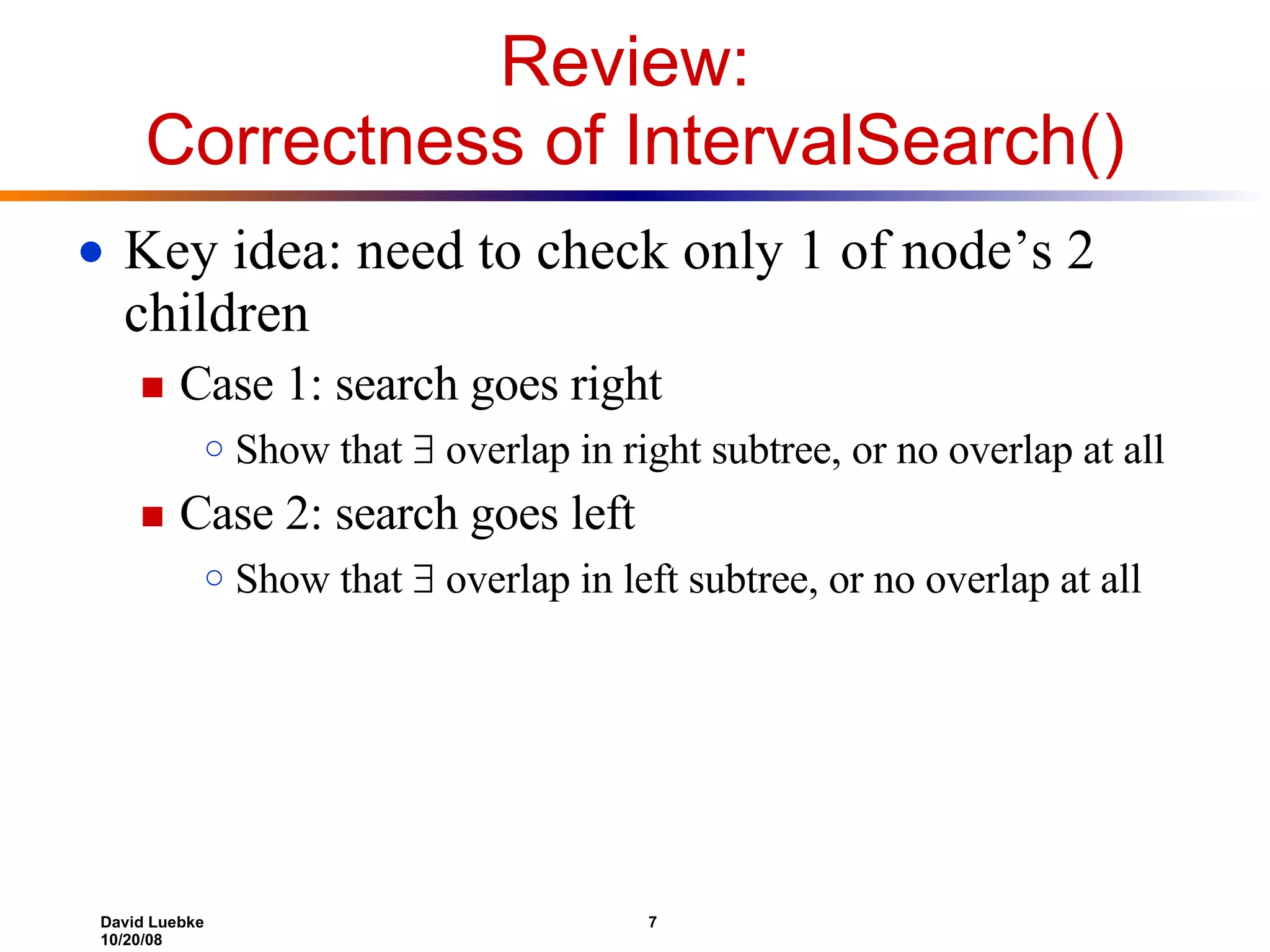

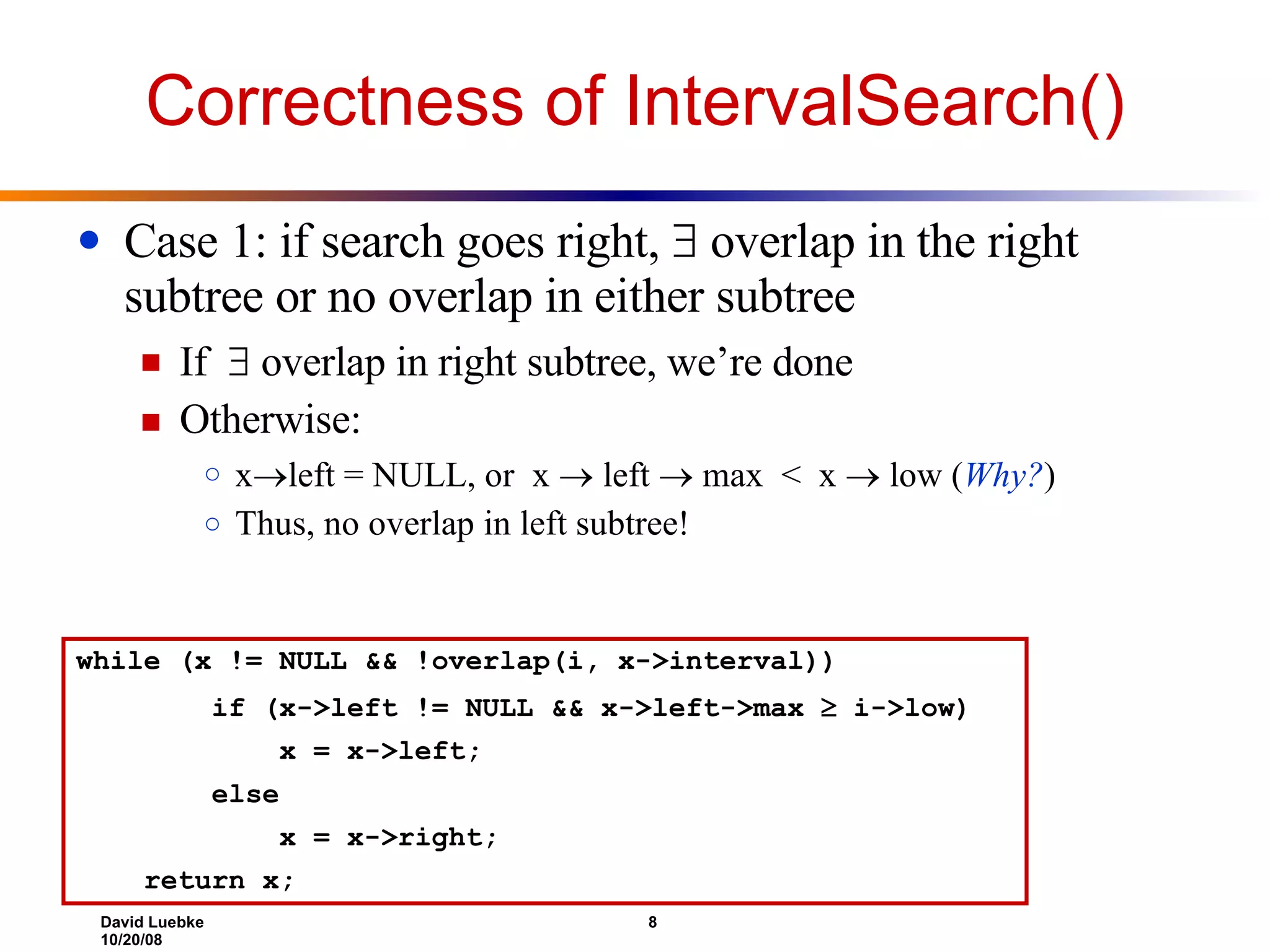

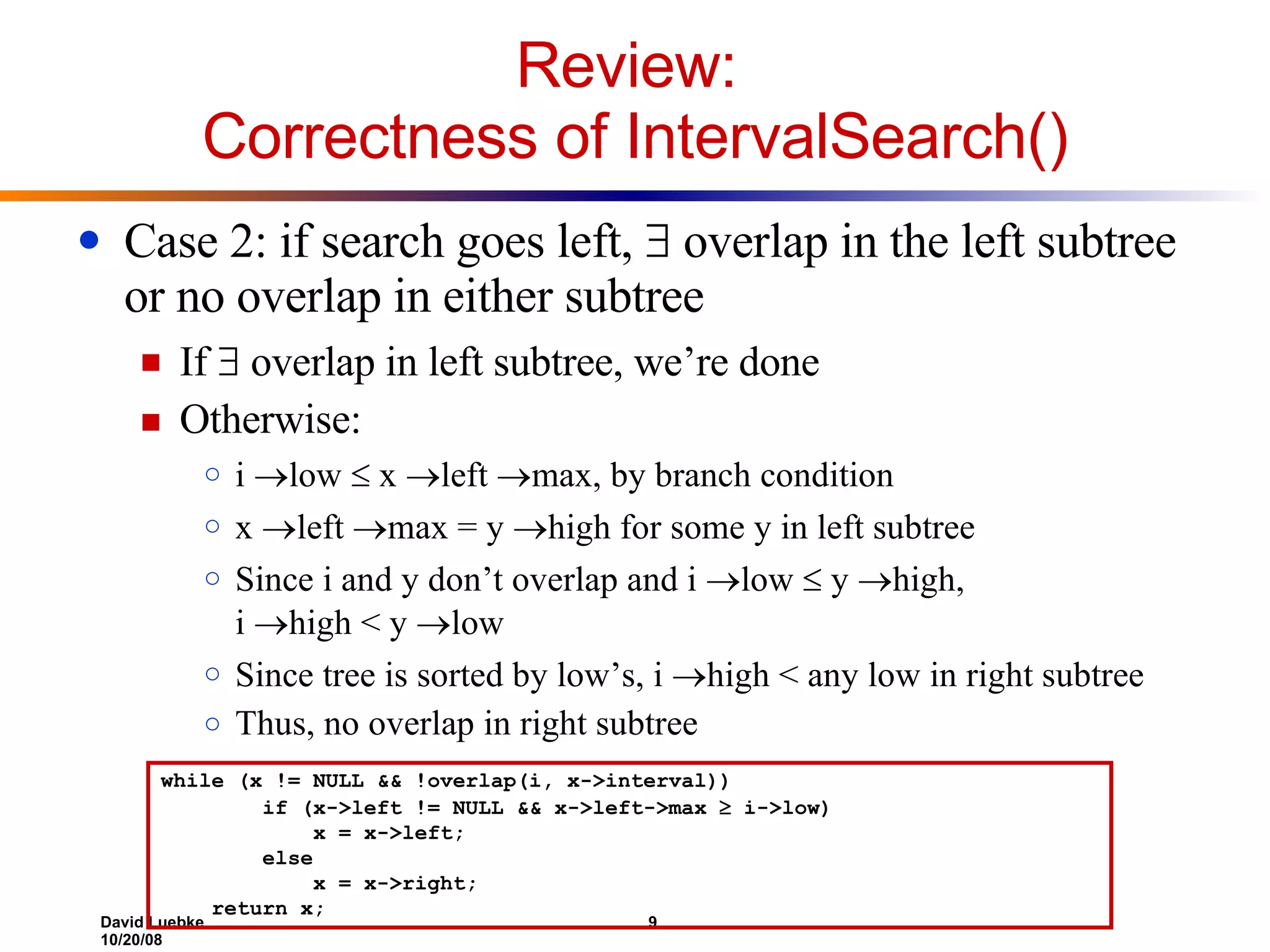

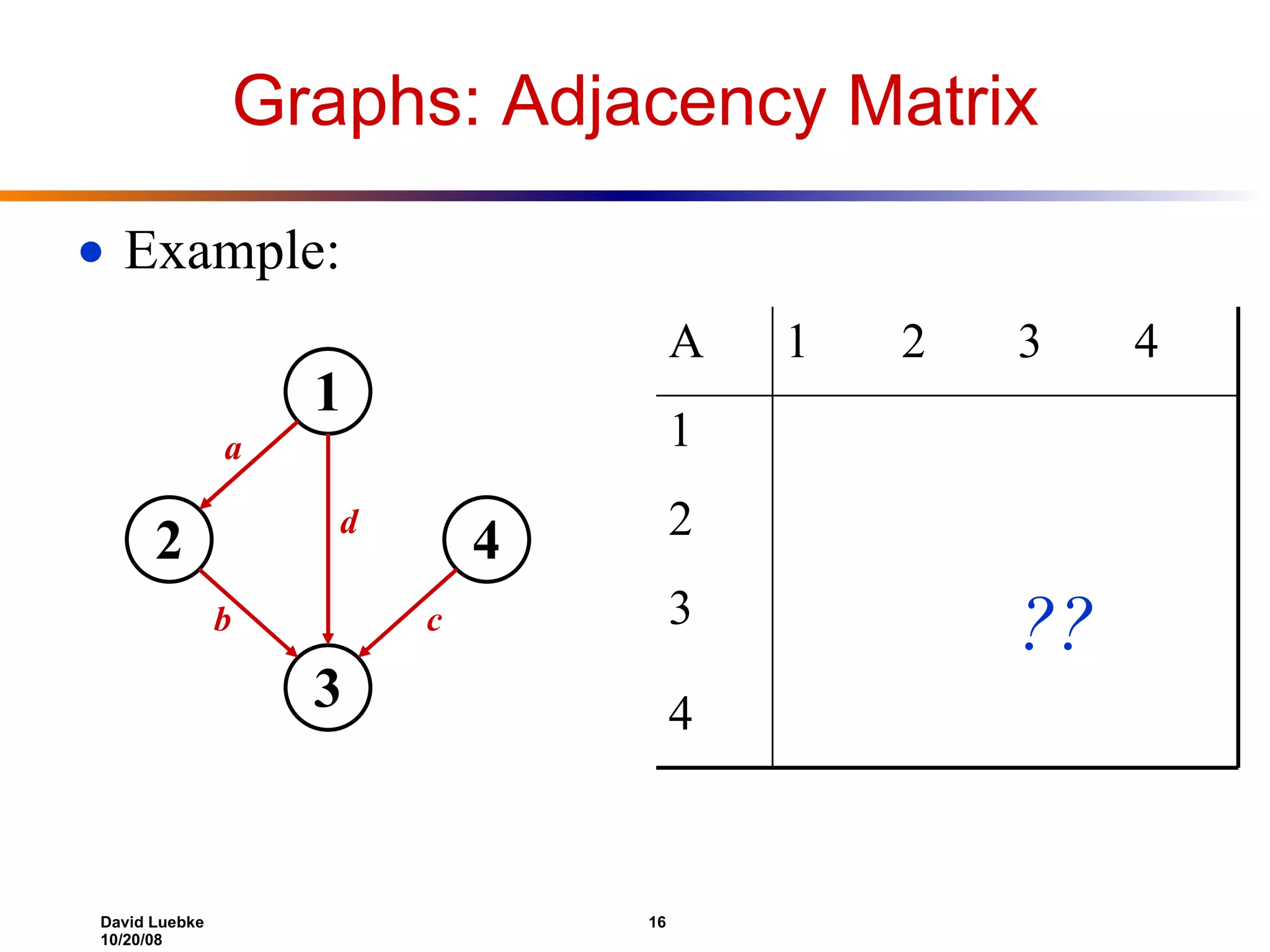

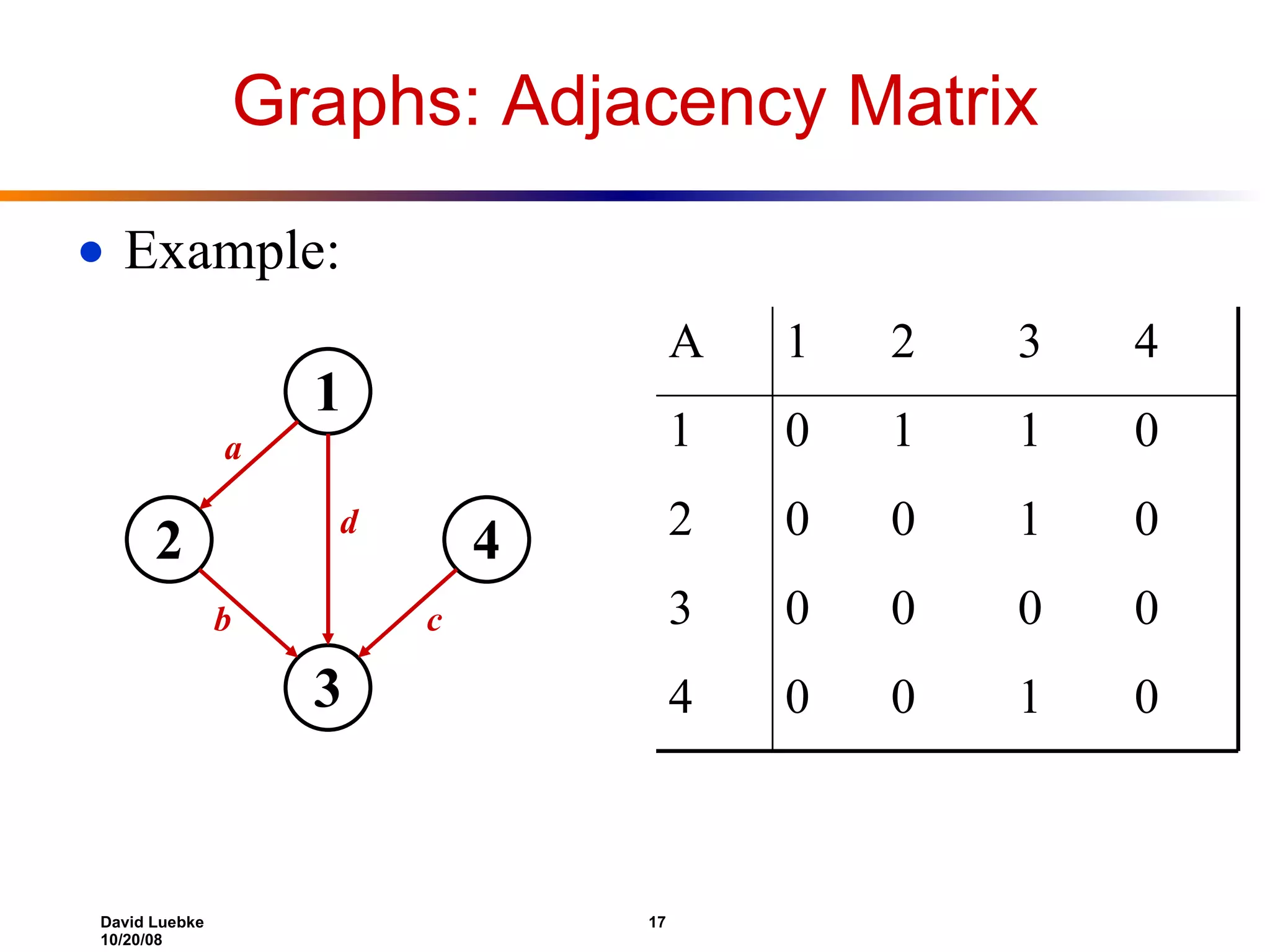

The document discusses interval trees and breadth-first search (BFS) algorithms. Interval trees are used to maintain a set of intervals and efficiently find overlapping intervals given a query. BFS is a graph search algorithm that explores all neighboring vertices of a starting node before moving to neighbors of neighbors. BFS builds a breadth-first tree and calculates the shortest path distances from the source node in O(V+E) time and space.

![Interval Trees The problem: maintain a set of intervals E.g., time intervals for a scheduling program: 10 7 11 5 8 4 18 15 23 21 17 19 i = [7,10]; i low = 7; i high = 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture22-1224487699183491-8/75/lecture-17-2-2048.jpg)

![Review: Interval Trees The problem: maintain a set of intervals E.g., time intervals for a scheduling program: Query: find an interval in the set that overlaps a given query interval [14,16] [15,18] [16,19] [15,18] or [17,19] [12,14] NULL 10 7 11 5 8 4 18 15 23 21 17 19 i = [7,10]; i low = 7; i high = 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture22-1224487699183491-8/75/lecture-17-3-2048.jpg)

![Review: Interval Trees [17,19] 23 [5,11] 18 [21,23] 23 [4,8] 8 [15,18] 18 [7,10] 10 int max Note that:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture22-1224487699183491-8/75/lecture-17-5-2048.jpg)

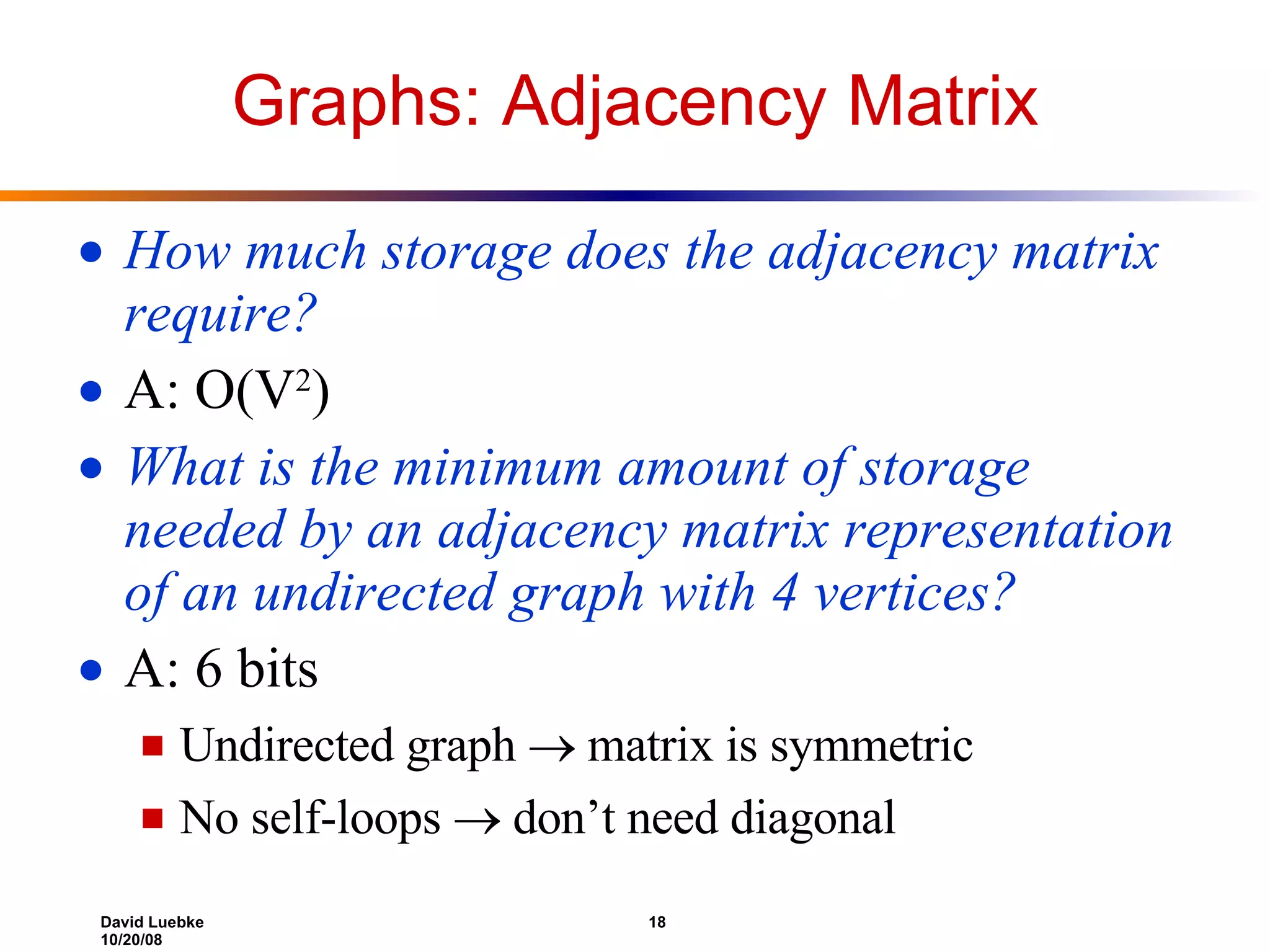

![Representing Graphs Assume V = {1, 2, …, n } An adjacency matrix represents the graph as a n x n matrix A: A[ i , j ] = 1 if edge ( i , j ) E (or weight of edge) = 0 if edge ( i , j ) E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture22-1224487699183491-8/75/lecture-17-15-2048.jpg)

![Graphs: Adjacency List Adjacency list: for each vertex v V, store a list of vertices adjacent to v Example: Adj[1] = {2,3} Adj[2] = {3} Adj[3] = {} Adj[4] = {3} Variation: can also keep a list of edges coming into vertex 1 2 4 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture22-1224487699183491-8/75/lecture-17-20-2048.jpg)