Your algorithm seems fine; it is indeed \$O(n)\$ time and \$O(n)\$ space. If you adjusted your code somewhat, you could reduce it to \$O(h)\$ space (ignoring input), where \$h\$ is the height of the tree; I'll come back to this later. One nit: it doesn't handle k == 0.

The major issue with this code is that it doesn't help the reader understand it. Your names describe the mechanics of the named item, not its purpose (recurse, list, items -- what purpose do these have in your algorithm?). The classes are divided oddly -- encapsulation is broken (e.g. almost all of your code has to know the precise representation of the tree).

Encapsulation of the tree representation

KDistanceFromLeaves<T>'s constructor takes a List<T>. Here you're making assumptions about the representation of the tree that have nothing to do with its type. The easiest solution is probably to take a TreeNode<T> instead (and make TreeNode<T> a public class instead of a nested class of KDistanceFromLeaves<T>. Alternatively, you could implement something like

interface IterableTree<T> { interface Iterator { T getValue(); boolean hasLeft(); /** The behavior of getLeft() is undefined when !hasLeft() */ Iterator getLeft(); /** The behavior of getRight() is undefined when !hasRight() */ boolean hasRight(); Iterator hasRight(); } boolean isEmpty(); /** The behavior of getRoot() is undefined when isEmpty(). */ Iterator getRoot(); }

Two implementations arise immediately to mind:

class TreeNode<T> implements IterableTree<T>, IterableTree<T>.Iterator { private final T value; private TreeNode<T> left = null; private TreeNode<T> right = null; public TreeNode(T value) { this.value = value; } public void setLeft(TreeNode<T> left) { this.left = left; } public void setRight(TreeNode<T> right) { this.right = right; } /** A non-null TreeNode<T> is never an empty tree */ @Override public boolean isEmpty() { return false; } @Override public TreeNode<T> getRoot() { return this; } @Override public T getValue() { return value; } @Override public TreeNode<T> getLeft() { return left; } @Override public boolean hasRight() { return right != null; } @Override public TreeNode<T> getRight() { return right; } } public ListBackedTree<T> implements IterableTree<T> { private final List<T> nodes; public ListBackedTree(List<T> nodes) { this.nodes = nodes } private class Iterator implements IterableTree<T>.Iterator { private int index; public Iterator(int index) { this.index = index; } @Override public T getValue() { return nodes.get(index); } @Override public boolean hasLeft() { return 2 * index + 1 < nodes.size(); } @Override public Iterator getLeft() { return new Iterator(2 * index + 1); } @Override public boolean hasRight() { return 2 * index + 2 < nodes.size(); } @Override public Iterator getRight() { return new Iterator(2 * index + 2); } } @Override public boolean isEmpty() { return nodes.isEmpty(); } @Override public Iterator getRoot() { return new Iterator(0); } }

If you use IterableTree<T> instead of List<T>, your users don't have to convert between tree representations just to use your algorithm -- they can use whatever tree they've already got lying around.

As a side note, from an encapsulation point of view, with the code you had, create should be a static method on TreeNode<T> (or even be renamed to TreeNode<T>.TreeNode(List<T>)), not a private method on KDistanceFromTreeLeaves<T>. Classes should be responsible for understanding their own representation.

Rewriting the algorithm

As I mentioned above, your algorithm is fine. The problem comes in the way it is presented.

I'd start by making kDistanceFromLeaf a static method that takes a tree as an argument rather than a method on a class whose only member is a tree. It sort of made sense with your code, since you transformed the tree passed to the constructor and so wanted to save the effort of transformation each time you called your algorithm. However, your transformation was simply a change in representation -- you don't do any additional computation. Thus, it makes more sense to abstract the algorithm away from the representation than to transform the data and make your algorithm depend on a single representation.

How about the return value? A List is ordered and may contain multiple copies of a given value. That doesn't really model our return value. What we really want to return is a Set -- this is an unordered collection that contains at most one copy of each value.

Next up is naming. What is items? Well, it's a list of the current node's ancestors. So let's call it ancestors. What about list? This is a list of the nodes that satisfy our condition. We could call it found or targets. visited is obviated by using a Set instead of a List.

Finally, comments. First, it is sensible to document the purpose of classes and methods using doc comments. Second, it is sometimes very useful to add comments that explain why code is written a certain way.

With all that in mind, here's another whack at implementing the algorithm:

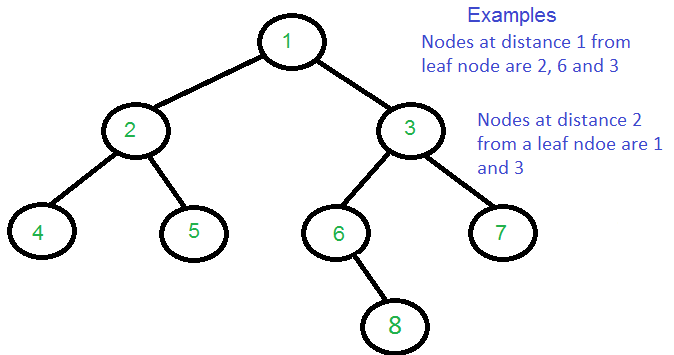

/** Collects implementations of interview questions */ class InterviewProblems { /** * Given a tree, determines which nodes are exactly k distance from * a leaf node (that is, nodes that are k levels above a leaf node). */ public static <T> Set<T> kDistanceFromLeaf( IterableTree<T> tree, int k) { Set<T> found = new HashSet<>(); if (tree == null || tree.isEmpty()) return found; computeKDistanceFromLeaf(tree.getRoot(), k, new ArrayList<T>(), found); return found; } private static <T> boolean isLeafNode(IterableTree<T>.Iterator node) { return !node.hasLeft() && !node.hasRight(); } /** Recursive helper function for {@link #kDistanceFromLeaf}. */ private static <T> void computeKDistanceFromLeaf( IterableTree<T>.Iterator node, int k, List<T> ancestors, Set<T> found) { ancestors.add(node.getValue()); // If this is a leaf node, its kth ancestor should be added to found. if (isLeafNode(node) && ancestors.size() > k) { found.add(ancestors.get(ancestors.size() - 1 - k)); } if (node.hasLeft()) computeKDistanceFromLeaf(node.getLeft(), k, ancestors, found); if (node.hasRight()) computeKDistanceFromLeaf(node.getRight(), k, ancestors, found); ancestors.remove(ancestors.size() - 1); } }

Minor comments

You use final a lot for local variables. That's fine (and as someone who uses C++ a lot, I certainly understand the instinct). However, a more common Java style is only to mark local variables final when they are to be used by inner classes. final is not nearly as useful as C++'s const and the cost-benefit tradeoff (cost: final is sprinkled liberally through the code; benefit: you know that the reference won't be reassigned, but not that the objects won't be modified) is less in favor of adding final in Java than const in C++.

Yay unit tests! One question: You've given an example in the problem description -- why not write a unit test that confirms that the code correctly works the example?

A final comment: I haven't compiled, much less tested, the code in this example, so use it with care and let me know if you have any questions!