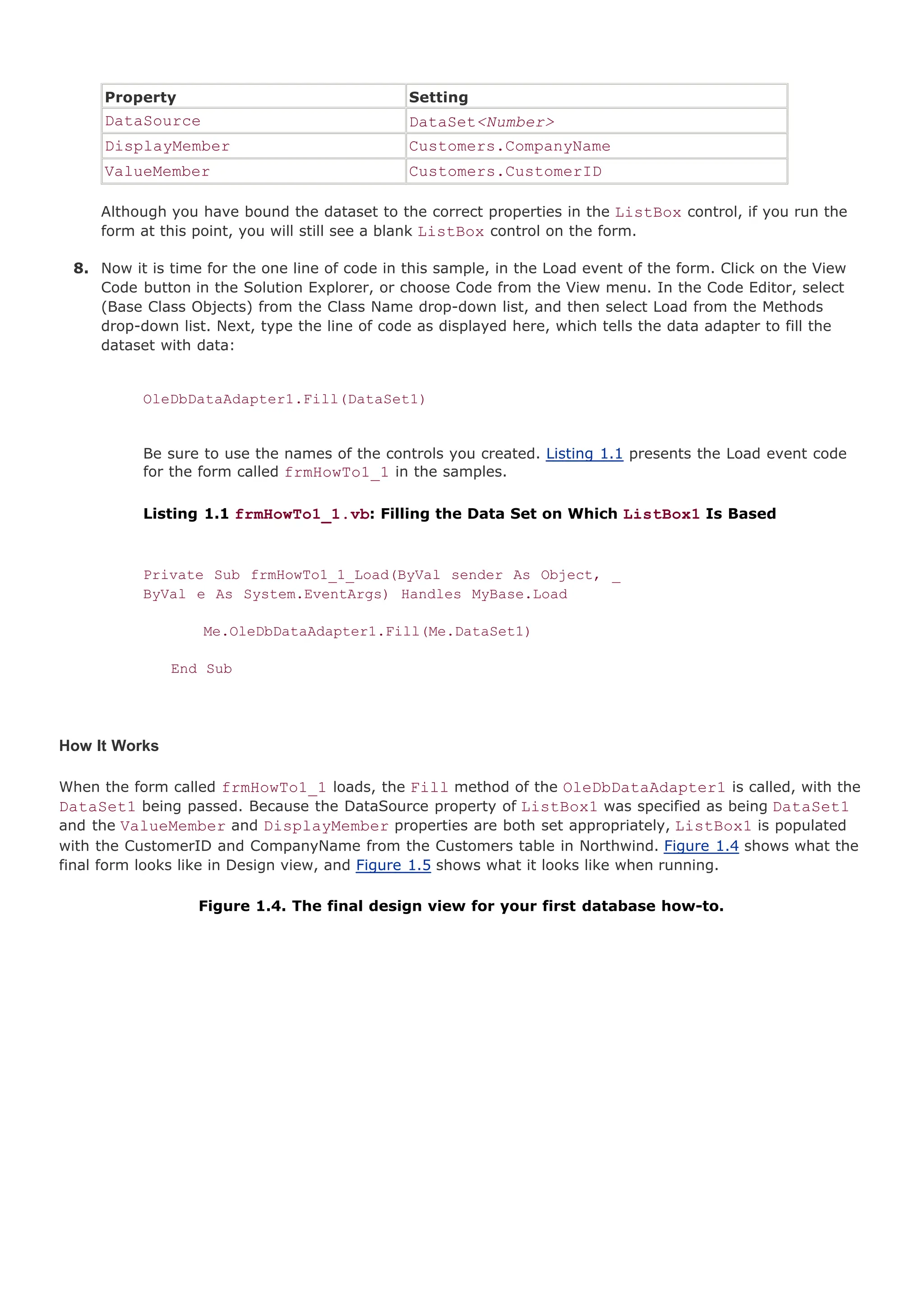

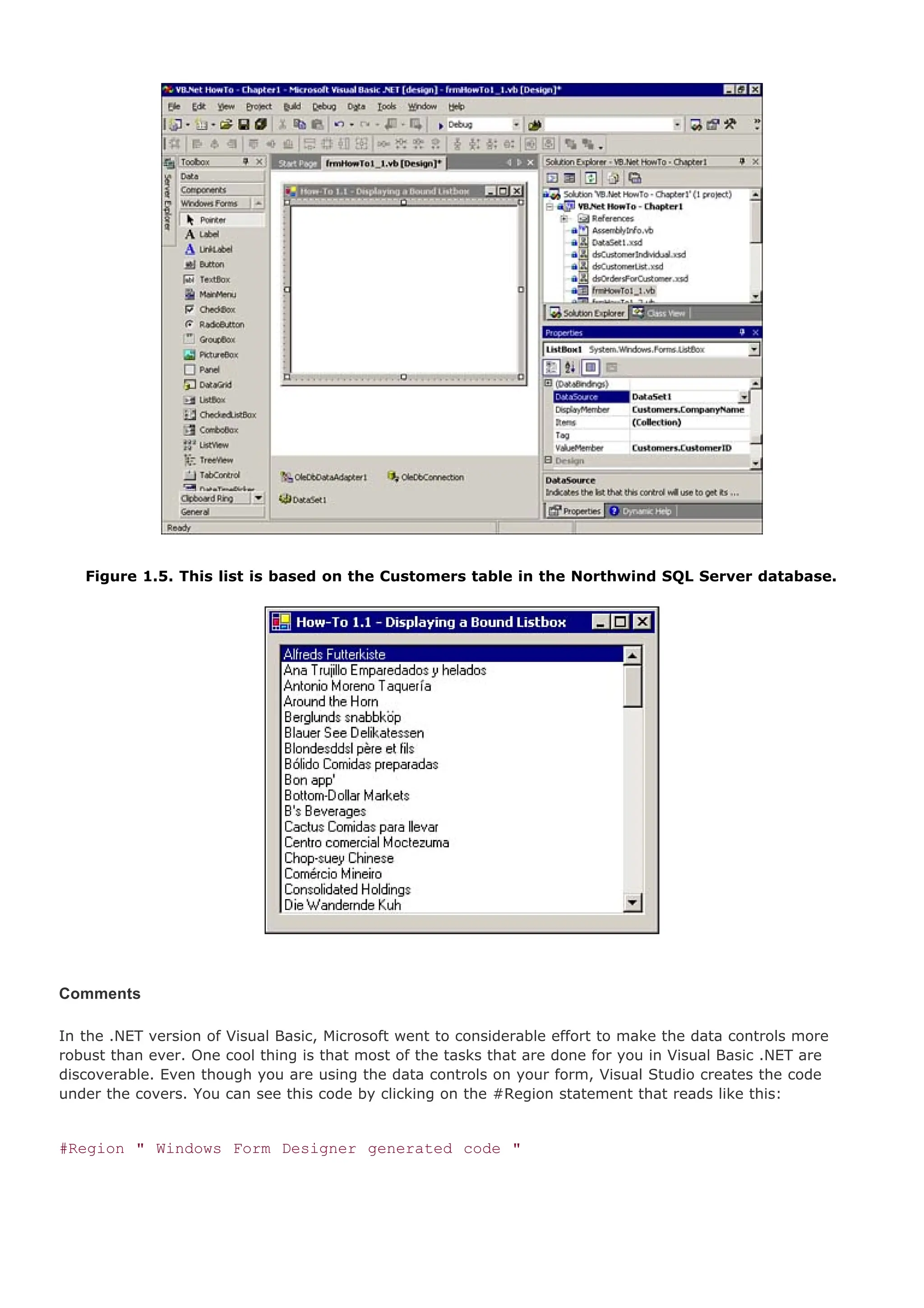

Database Programming with Visual Basic NET and ADO NET Tips Tutorials and Code 1st Edition Barker Database Programming with Visual Basic NET and ADO NET Tips Tutorials and Code 1st Edition Barker Database Programming with Visual Basic NET and ADO NET Tips Tutorials and Code 1st Edition Barker

![[ Team LiB ] 1.1 Create a Bound List Box It used to be that when you wanted to create a data entry form, you just assigned a recordset to the data control and allowed the users to scroll through the data, making changes as needed. When you're dealing with Client Server or Web applications, this just doesn't cut it. One of the first things you need to do is provide a method to limit the amount of data so that users can pick which record they want to edit/view, without pulling all the fields of a table over the Net—either LAN or Internet. List boxes and combo boxes help with that. In this How-To, you will learn how to set up two data controls: OleDbDataAdapter and DataSet. These controls enable you to populate a list box with one line of code. You want to see a list of customers on your Windows form in a ListBox control. You don't want to write code at this point. You only want to prototype a form, so you just want to use bound data controls. How do you create a list box and bind it using the data controls? Technique To get started with learning about any of the objects used for data in .NET, it's important to talk about what .NET Namespaces are and how to use them. Using .NET Namespaces The .NET Framework contains a big class library. This class library consists of a number of Namespaces. These Namespaces are made up of various classes that allow us to create our objects. All of the objects and classes that make up the .NET objects, such as forms, controls, and the various data objects, can be found in Namespaces. Namespaces also can be made up of other Namespaces. For example, there is a Namespace called System.Data. Although this Namespace has classes in it, such as DataSet and DataTable, it also has Namespaces within it called System.Data.OleDb and System.Data.SQLClient, as well as others. To check out the .NET Namespaces, choose Object Browser from the View menu. You can then expand the System.Data Namespace to see the other Namespaces contained within. If you are positive that the database you are going to be working with is SQL Server, then you would be far better served performance-wise to use the classes found in the System.Data.SQLClient Namespace. However, if you are not sure what database you will be working against, you should use the classes found in System.Data.OleDb. For this book, I am using objects created from the classes in the System.Data.OleDb Namespace. That way, you can use the routines against other databases with less modifications. Tip](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-11-2048.jpg)

![Beware: There is much code here, and you don't want to change it. You can learn a lot from reading it though. As you continue to use the Data Controls shown here, you will become comfortable with changing various properties and getting more power and use out of them. [ Team LiB ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-18-2048.jpg)

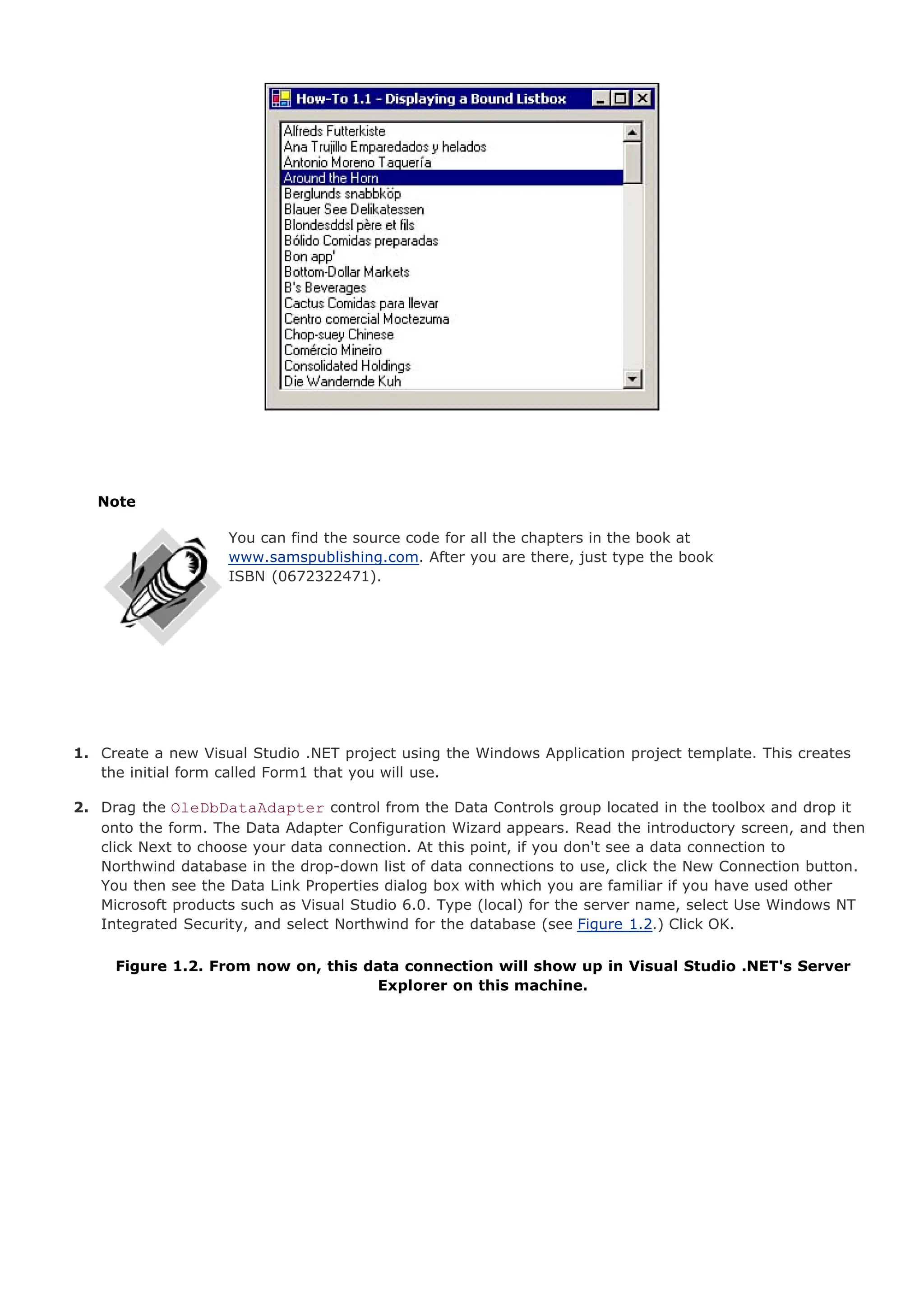

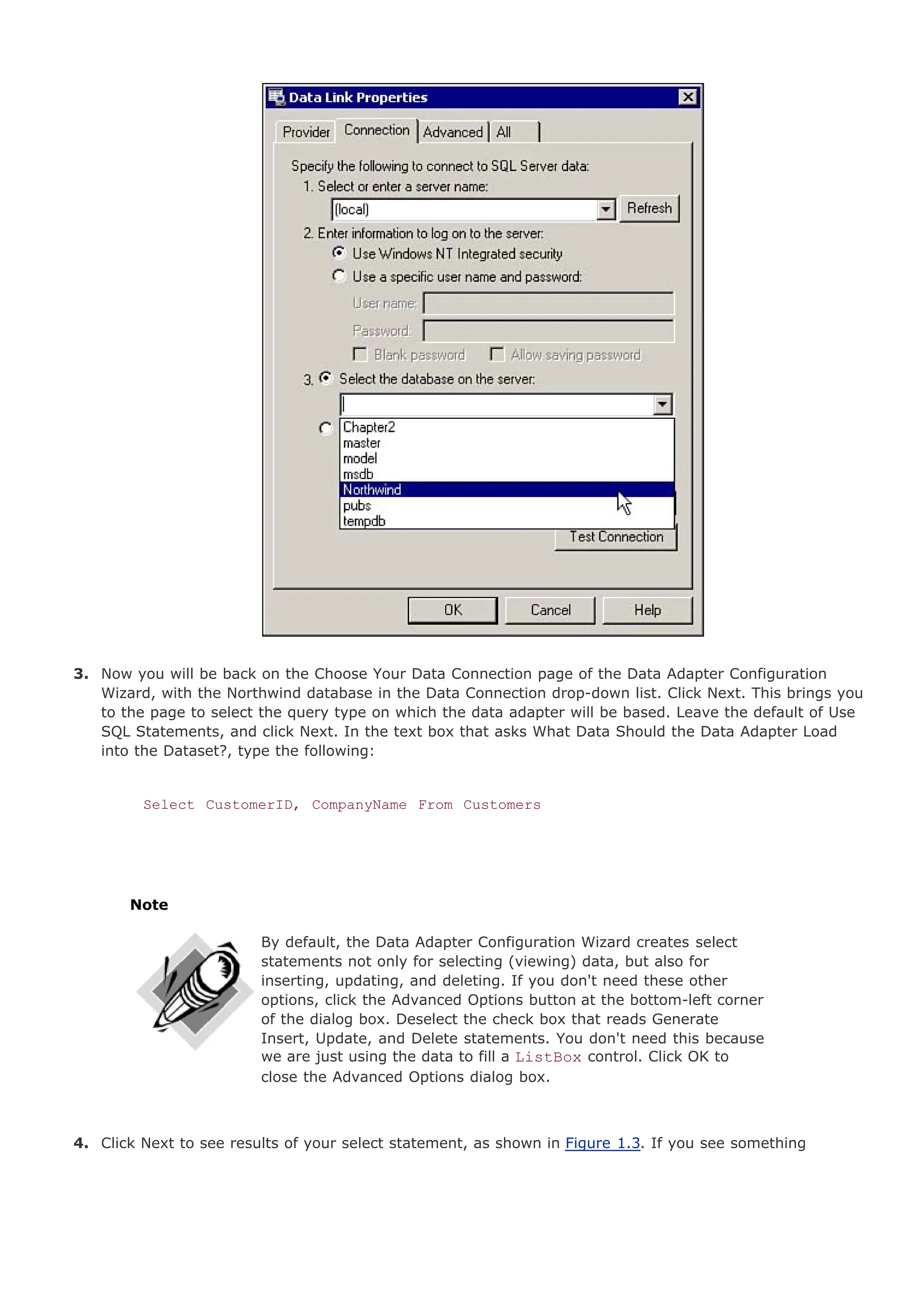

![[ Team LiB ] 1.2 Limit the Data Displayed in a Bound List Box Even populating a list box with a couple of columns from a table full of data can be a big performance hit. This How-To shows you how to create a parameterized SQL statement to limit the items that are displayed in the list box, thus giving you better performance on your forms. You have hundreds of thousands of customers in your database, and you don't want the list box loaded up with the whole customer table. How can you limit the data that is displayed in your list box? Technique You are going to make a copy of the form that you created in How-To 1.1. You will then add a Label and TextBox control that the Select statement contained within the OleDbDataAdapter control will query against to limit the data displayed in the list box. A command button will be added to allow you to call the Fill method of the OleDbDataAdapter control whenever you update the text box, and then you can click the command button (see Figure 1.6 ). Figure 1.6. You can now limit the amount of data loaded into the list box. Steps To get started with this How-To, right-click the form you created in How-To 1.1, which should be listed in the Solutions Explorer. Choose Copy from the pop-up menu. Next, right-click the project in the Solution Explorer, and choose Paste from the pop-up menu. You will now have a new Class object in the Solutions Explorer called Copy Of whatever the previous name of the form was . Rename the new form that you have created to the name you desire. Then, with that form highlighted, click on the Code button above the Solutions Explorer. Change the first line of code to say this: Public Class <Name of the new form>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-19-2048.jpg)

![Try entering a few other letters, and then try entering no letters. What happens? You limit the list more by the number of letters you enter, and you get all entries when you don't enter any letters. The method displayed here, although simple, is powerful, and it can be used in a variety of ways. You can continue building on this form for the next few How-Tos. If you want to copy your form and start a new one as described at the beginning of the steps for this one, you have the instructions there. Otherwise, by the time you reach How-To 1.8, you will have a data entry form that you can use. Each step, however, is available in the sample solution for this chapter. [ Team LiB ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-22-2048.jpg)

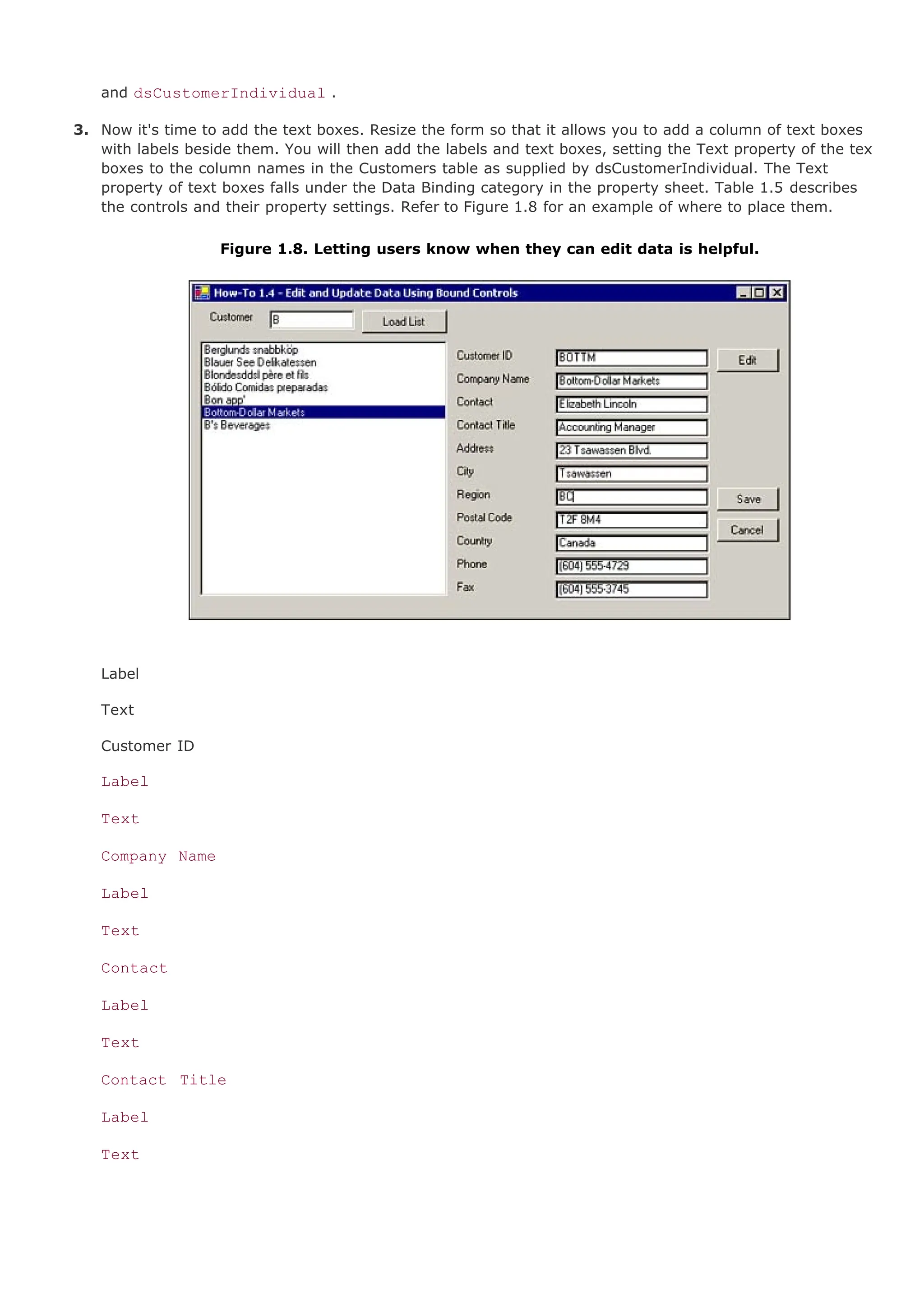

![[ Team LiB ] 1.3 Bind and View Individual Text Boxes Based Off a Selected List Box Item Using a list box similar to the one in the previous How-To, in this How-To, you will learn how to create additional OleDbDataAdapter s and DataSets and bind them to individual text boxes for viewing data. Although the list box is nice for displaying a couple of fields in my form and limiting the rows displayed, how do you list the detail in individual text boxes by clicking on an item in the list box? Technique You are going to enhance the form that you created in How-To 1.2 to use additional data controls, specifically another data adapter and dataset. You will set up the select statement in the new data adapter to take the selected list box item as a parameter. The dataset will then be filled with data, and some text boxes with the dataset set as the data source will display the current record. You can see an example of this in Figure 1.7 . Figure 1.7. You can bind text boxes to datasets as well as list boxes. Steps To go further with the form with which you have been working, you will want to rename the data adapter, dataset, and list box currently on the form to something more meaningful. You can see this in Table 1.4 . ListBox Name ListBox1 lstCustomers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-23-2048.jpg)

![brandy; and, finally, we agreed that we would go and see the poor fellow’s corpse, and witness, if necessary, his burial. Flapper, who had joined us, was the first to propose this visit: he said he did not mind the fifteen francs which Jack owed him for billiards, but that he was anxious to get back his pistol. Accordingly, we sallied forth, and speedily arrived at the hotel which Attwood inhabited still. He had occupied, for a time, very fine apartments in this house; and it was only on arriving there that day, that we found he had been gradually driven from his magnificent suite of rooms au premier, to a little chamber in the fifth story: —we mounted, and found him. It was a little shabby room, with a few articles of rickety furniture, and a bed in an alcove; the light from the one window was falling full upon the bed and the body. Jack was dressed in a fine lawn shirt: he had kept it, poor fellow, to die in; for in all his drawers and cupboards, there was not a single article of clothing: he had pawned everything by which he could raise a penny—desk, books, dressing-case, and clothes; and not a single halfpenny was found in his possession.[2] He was lying as I have drawn him, one hand on his breast, the other falling towards the ground. There was an expression of perfect calm on the face, and no mark of blood to stain the side towards the light. On the other side, however, there was a great pool of black blood, and in it the pistol; it looked more like a toy than a weapon to take away the life of this vigorous young man. In his forehead, at the side, was a small black wound; Jack’s life had passed through it; it was little bigger than a mole. . . . . . ‘Regardez un peu,’ said the landlady; ‘messieurs, il m’a gâté trois matelas, et il me doit quarante quatre francs.’ This was all his epitaph: he had spoiled three mattresses, and owed the landlady four-and-forty francs. In the whole world there was not a soul to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-37-2048.jpg)

![time to be wicked; except in the case of a siege and the sack of a town, when a little licence can offend nobody.’] By the time that my friend had concluded Schneider’s biography, we had grown tolerably intimate, and I imparted to him (with that experience so remarkable in youth) my whole history—my course of studies, my pleasant country life, the names and qualities of my dear relations, and my occupations in the vestry before religion was abolished by order of the Republic. In the course of my speech I recurred so often to the name of my cousin Mary, that the gentleman could not fail to perceive what a tender place she had in my heart. Then we reverted to The Sorrows of Werther, and discussed the merits of that sublime performance. Although I had before felt some misgivings about my new acquaintance, my heart now quite yearned towards him. He talked about love and sentiment in a manner which made me recollect that I was in love myself; and you know that when a man is in that condition, his taste is not very refined, any maudlin trash of prose or verse appearing sublime to him, provided it correspond, in some degree, with his own situation. ‘Candid youth!’ cried my unknown, ‘I love to hear thy innocent story, and look on thy guileless face. There is, alas! so much of the contrary in this world, so much terror and crime and blood, that we who mingle with it are only too glad to forget it. Would that we could shake off our cares as men, and be boys, as thou art, again!’ Here my friend began to weep once more, and fondly shook my hand. I blessed my stars that I had, at the very outset of my career, met with one who was so likely to aid me. What a slanderous world it is! thought I; the people in our village call these Republicans wicked and bloody-minded; a lamb could not be more tender than this sentimental bottle-nosed gentleman! The worthy man then gave me to understand that he held a place under Government. I was busy in endeavouring to discover what his situation might be, when the door of the next apartment opened, and Schneider made his appearance. At first he did not notice me, but he advanced to my new acquaintance, and gave him, to my astonishment, something very like a blow. ‘You drunken, talking fool,’ he said, ‘you are always after your time. Fourteen people are cooling their heels yonder, waiting until you have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13214-250627152054-96ea7be8/75/Database-Programming-with-Visual-Basic-NET-and-ADO-NET-Tips-Tutorials-and-Code-1st-Edition-Barker-58-2048.jpg)