The document introduces functional programming concepts using Scala, emphasizing immutability and algebraic data types modeled with sealed traits and case classes. It outlines key features such as pattern matching, recursion, and higher-order functions, while contrasting traditional object-oriented programming with functional programming paradigms. It also discusses type variance, tail recursion, and provides examples of list operations like fold, map, and filter.

![pure FP List sealed trait List[+A] case object Nil extends List[Nothing] case class Cons[+A] (head: A, tail: List[A]) extends List[A] object List { def apply[A](as: A*): List[A] = if (as.isEmpty) Nil else Cons(as.head, apply(as.tail: _*)) private def asString_internal[A](l: List[A]): String = l match { case Nil => "" case Cons(head,tail) => head.toString + " " + asString_internal(tail) } def toString[A](l: List[A]): String = "[ " + asString_internal(l) + "]" }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-6-2048.jpg)

![List ADT sealed trait List[+A] case object Nil extends List[Nothing] case class Cons[+A] (head: A, tail: List[A]) extends List[A] Here we define List as a trait, and 2 type of lists are defined, Nil as empty List, and Cons as non-empty List.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-10-2048.jpg)

![Type Variance sealed trait List[+A] A is just abstract type (generic) +A here is called covariant, means that if A` is A’s subtype, then List[A`] is List[A]’s subtype.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-11-2048.jpg)

: List[A] = if (as.isEmpty) Nil else Cons(as.head, apply(as.tail: _*)) … You can create constructor for the List trait with different signatures here, you can have multiple constructor here in companion object.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-12-2048.jpg)

: String = l match { case Nil => "" case Cons(head,tail) => head.toString + " " + asString_internal(tail) } def toString[A](l: List[A]): String = "[ " + asString_internal(l) + "]" } Now we define toString function here, we here use pattern matching to see what is the remaining list type between Nil and Cons. Pattern Matching is a very powerful feature in FP, and it can match into the multiple layers of objects, match types and much more.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-13-2048.jpg)

![OO/FP List sealed trait List[+A] { def head: A def tail: List[A] def isEmpty: Boolean override def toString = "[ " + asString_internal(this) + "]" private def asString_internal[B >: A](l: List[B]): String = l match { case Cons(head,tail) => head.toString + " " + asString_internal(tail) case _ => "" } } object List { def apply[A](as: A*): List[A] = if (as.isEmpty) Nil else Cons(as.head, apply(as.tail: _*)) } case object Nil extends List[Nothing] { override def isEmpty = true override def head: Nothing = throw new NoSuchElementException("head of empty list") override def tail: List[Nothing] = throw new UnsupportedOperationException("tail of empty list") } case class Cons[+A] (hd: A, tl: List[A]) extends List[A] { override def isEmpty = false override def head : A = hd override def tail : List[A] = tl }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-16-2048.jpg)

: String Here the B >: A is called lower bound in type variation, which means that, B must be a supertype of A. This is required to satisfy the type variance check (you can not use A here directly in place of B) check this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-17-2048.jpg)

![More List functions def sum(ints: List[Int]): Int = ints match { case Nil => 0 case Cons(x,xs) => x + sum(xs) } def product(ds: List[Double]): Double = ds match { case Nil => 1.0 case Cons(0.0, _) => 0.0 case Cons(x,xs) => x * product(xs) } These 2 common functions seems really similar, how we can generalize it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-18-2048.jpg)

(f: (A, B) => B): B = l match { case Nil => z case Cons(x, xs) => f(x, foldRight(xs, z)(f)) } def sum(l: List[Int]) = foldRight(l, 0)((x,y) => x + y) def product(l: List[Double]) = foldRight(l, 1.0)(_ * _) Here is the higher order function (function take function as parameter or output), a very power/interesting feature in FP. Here _ * _ means the first parameter * second parameter, which is a short hand way to write it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-19-2048.jpg)

(f: (B, A) => B): B = l match { case Nil => z case Cons(h,t) => foldLeft(t, f(z,h))(f) } def reverse[A](l: List[A]): List[A] = foldLeft(l, List[A]())((acc,h) => Cons(h,acc)) def foldRight[A,B](l: List[A], z: B)(f: (A,B) => B): B = foldLeft(reverse(l), z)((b,a) => f(a,b)) foldLeft is tail recursive, and it enforced (by the annotation) to optimize into loop in background, then we can use this FoldLeft to implement FoldRight (now no stack overflow](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-20-2048.jpg)

(f: A => B): List[B] = foldRight(la, Nil:List[B])((h,t) => Cons(f(h), t)) val a = List(1,2,3,4) List.map(a)(_+1) we get List(2,3,4,5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-21-2048.jpg)

: List[A] = Cons(a, Nil) def flatMap[A, B](la: List[A])(f: A => List[B]): List[B] = concat(foldRight(la, Nil:List[List[B]])((h,t) => Cons(f(h),t))) def join[A](lla: List[List[A]]): List[A] = flatMap(lla)(la => la) def compose[A,B,C](f: A => List[B], g: B => List[C]): A => List[C] = a => flatMap(f(a))(g) def apply[A,B](la: List[A])(f: List[A => B]): List[B] = flatMap(f)(t1 => flatMap(la)(t2 => unit(t1(t2)))) def map2[A,B,C](la: List[A], lb: List[B])(f: (A, B) => C): List[C] = apply(lb)(apply(la)(unit(f.curried))) def map[A, B](la: List[A])(f: A => B): List[B] = apply(la)(unit(f)) def fold[A](l: List[A])(z: A)(op: (A, A) ⇒ A): A = foldRight(l, z)(op) def filter[A](l: List[A])(f: A => Boolean): List[A] = foldRight(l, Nil:List[A])((h,t) => if (f(h)) Cons(h,t) else t)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-22-2048.jpg)

: List[A] fold[A](l: List[A])(z: A)(op: (A, A) ⇒ A): A filter[A](l: List[A])(f: A => Boolean): List[A] There are 3 groups: 1. flatMap/join/compose 2. apply/map2 3. map inside each group, the methods are equivalent to each other. G1 => G2 => G3, which means G1 can implement G2, G2 can implement G3. Powerful G1 > G2 > G3 Generality G1 < G2 < G3 OO sense, G1 inherit from G2 inherit from G3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-23-2048.jpg)

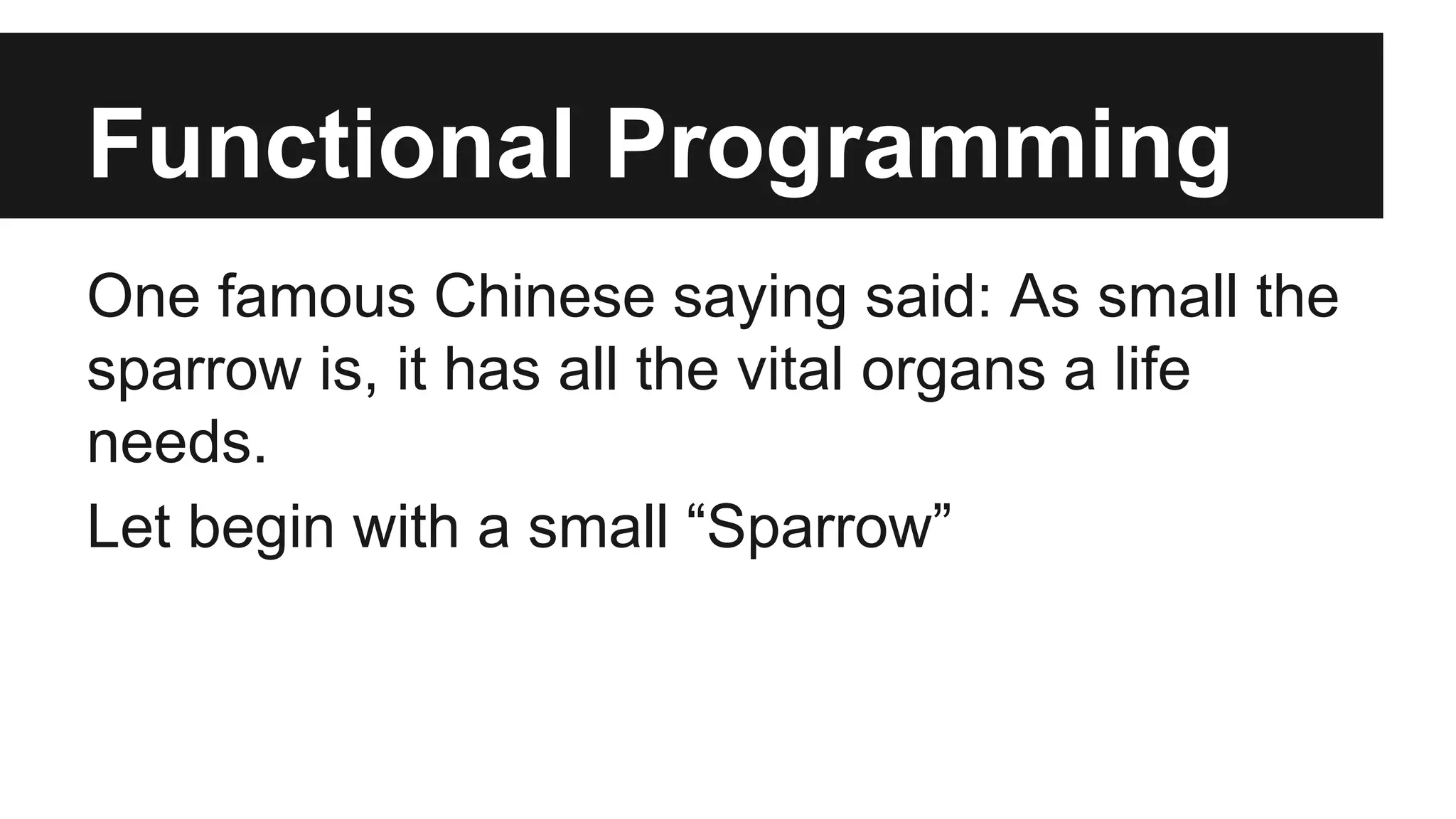

![for comprehension Use the OO/FP hybrid style code we can do def test = { val a = List(1,2) val b = List(3,4) for { t1 <- a t2 <- b } yield ((t1,t2)) } We get [ (1,3) (1,4) (2,3) (2,4) ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart1-140918134122-phpapp02/75/Fp-in-scala-part-1-26-2048.jpg)