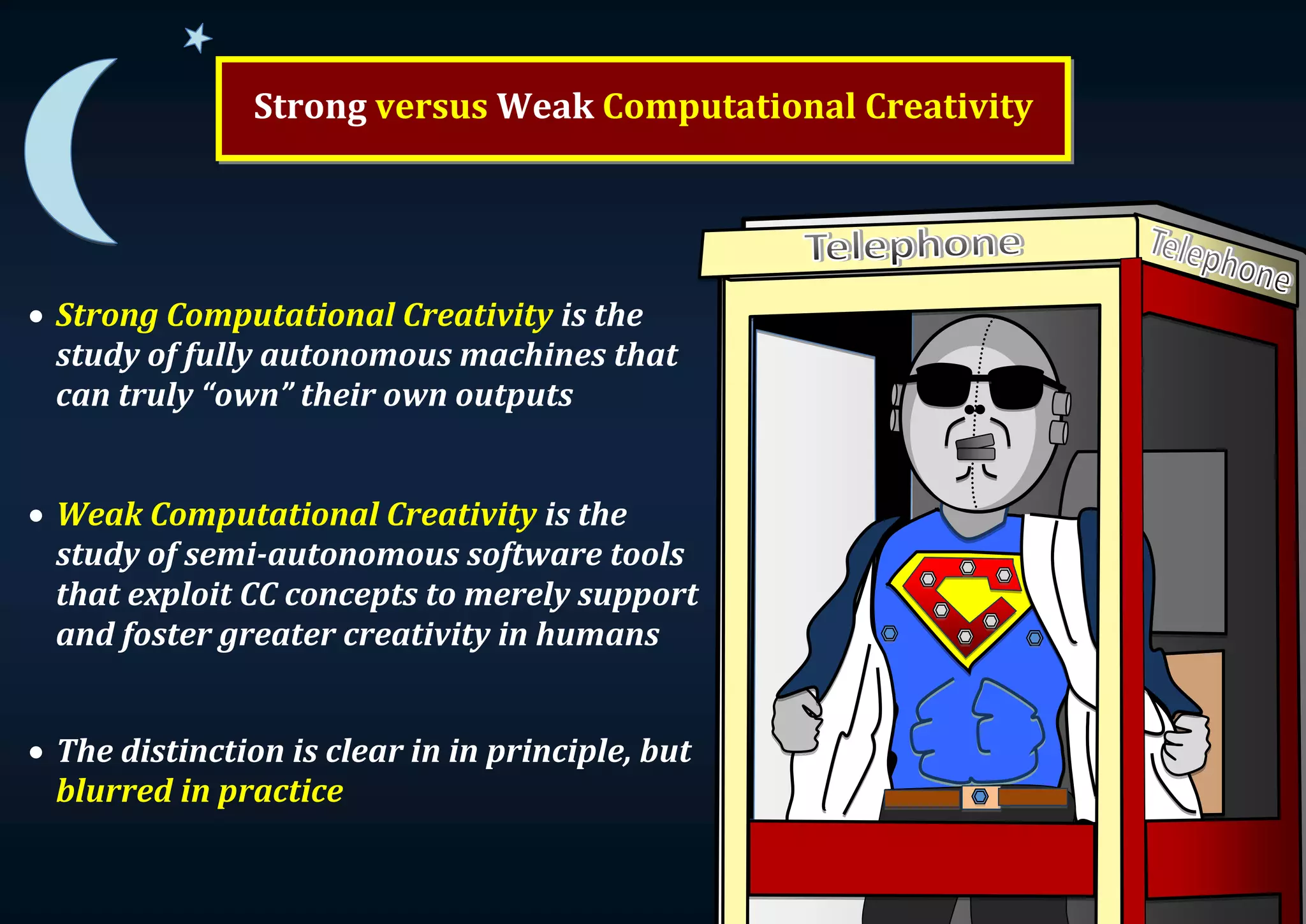

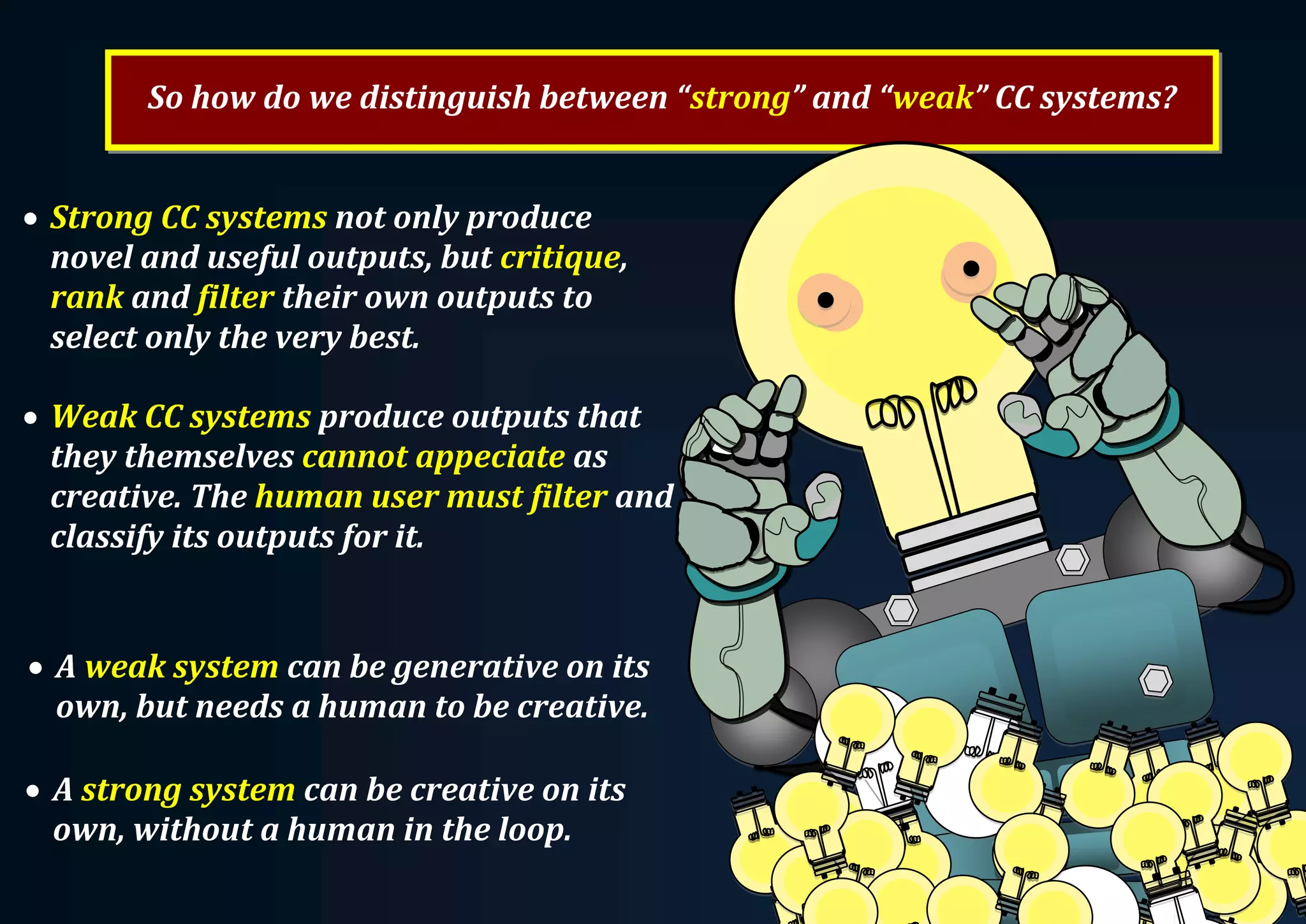

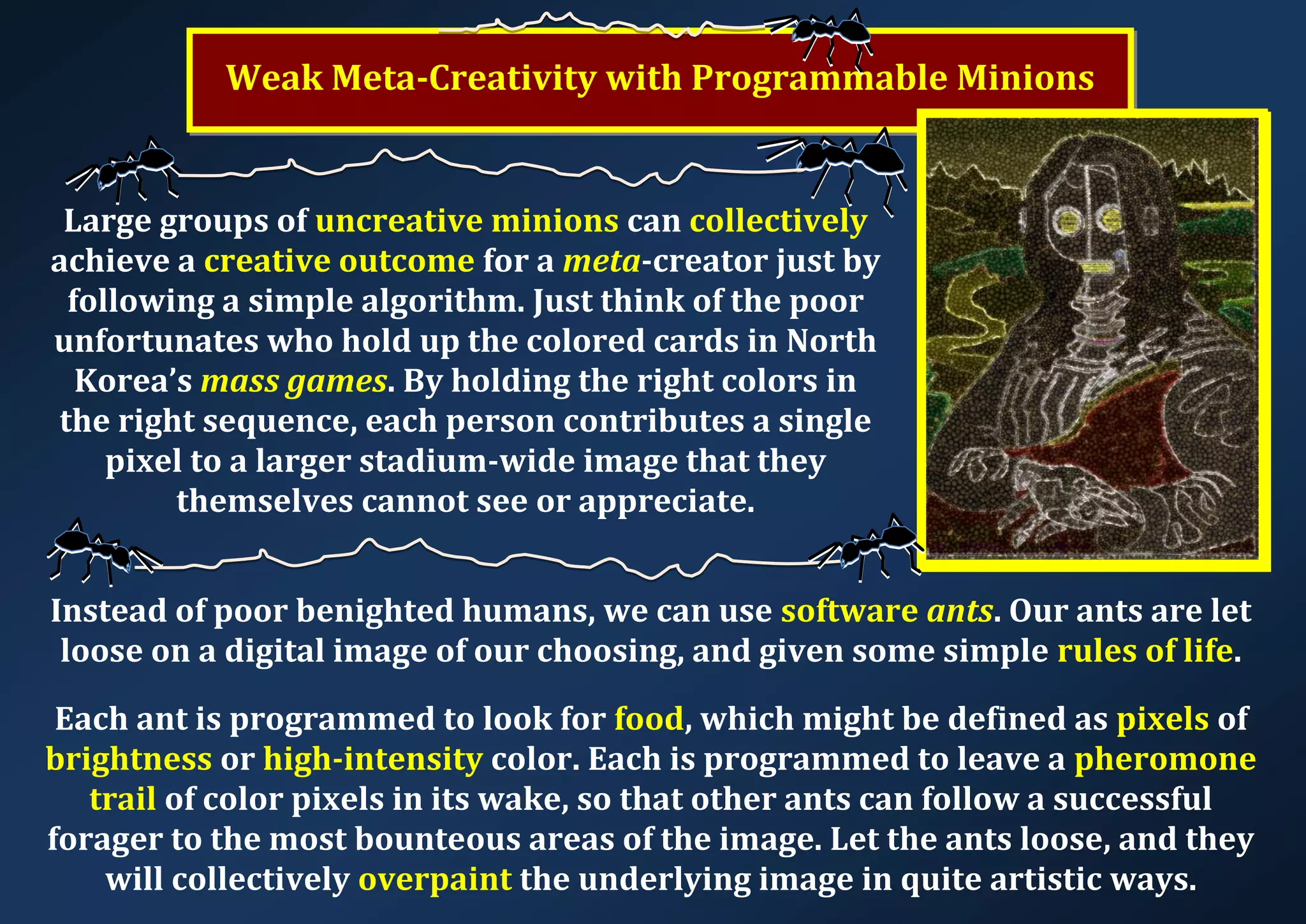

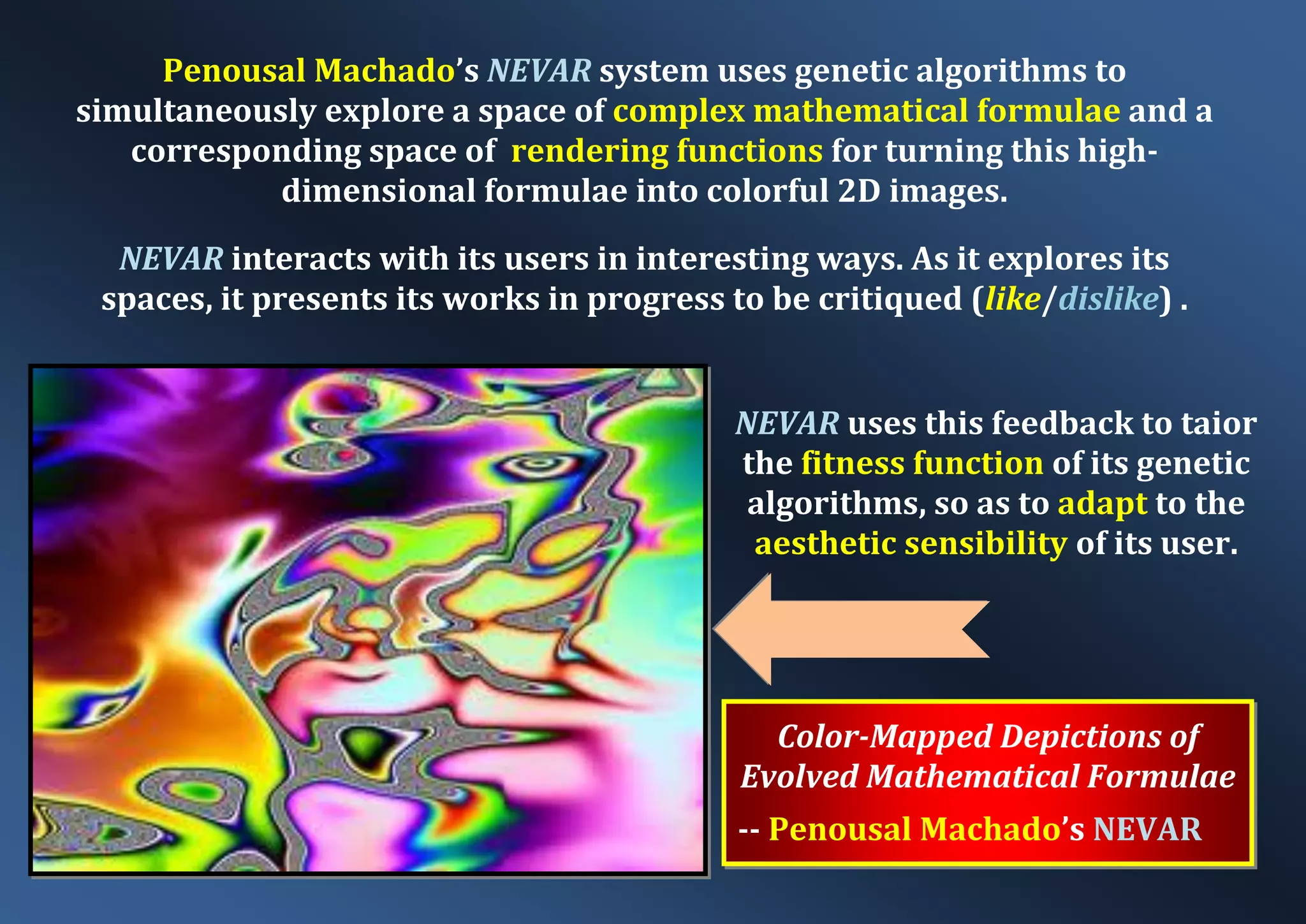

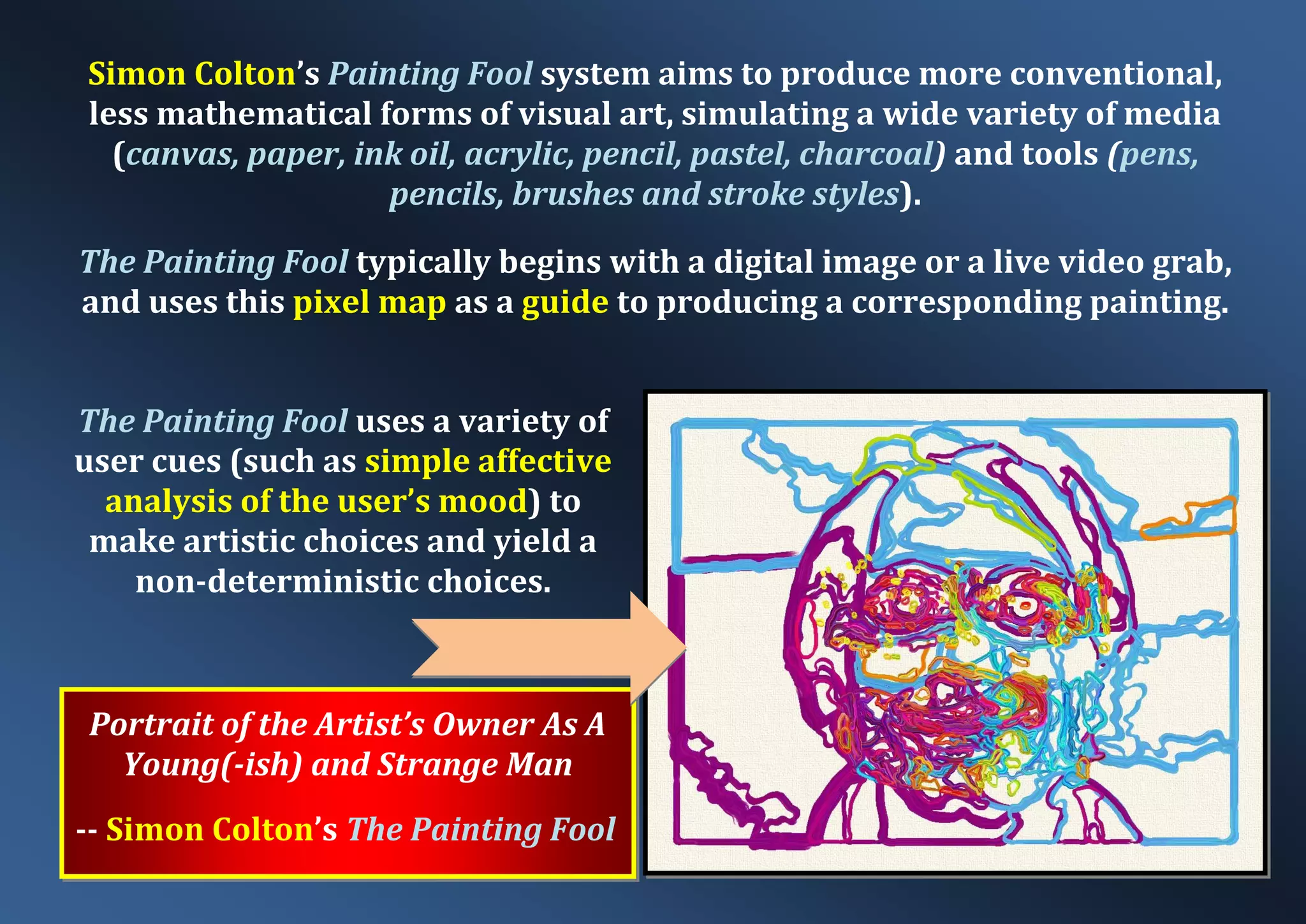

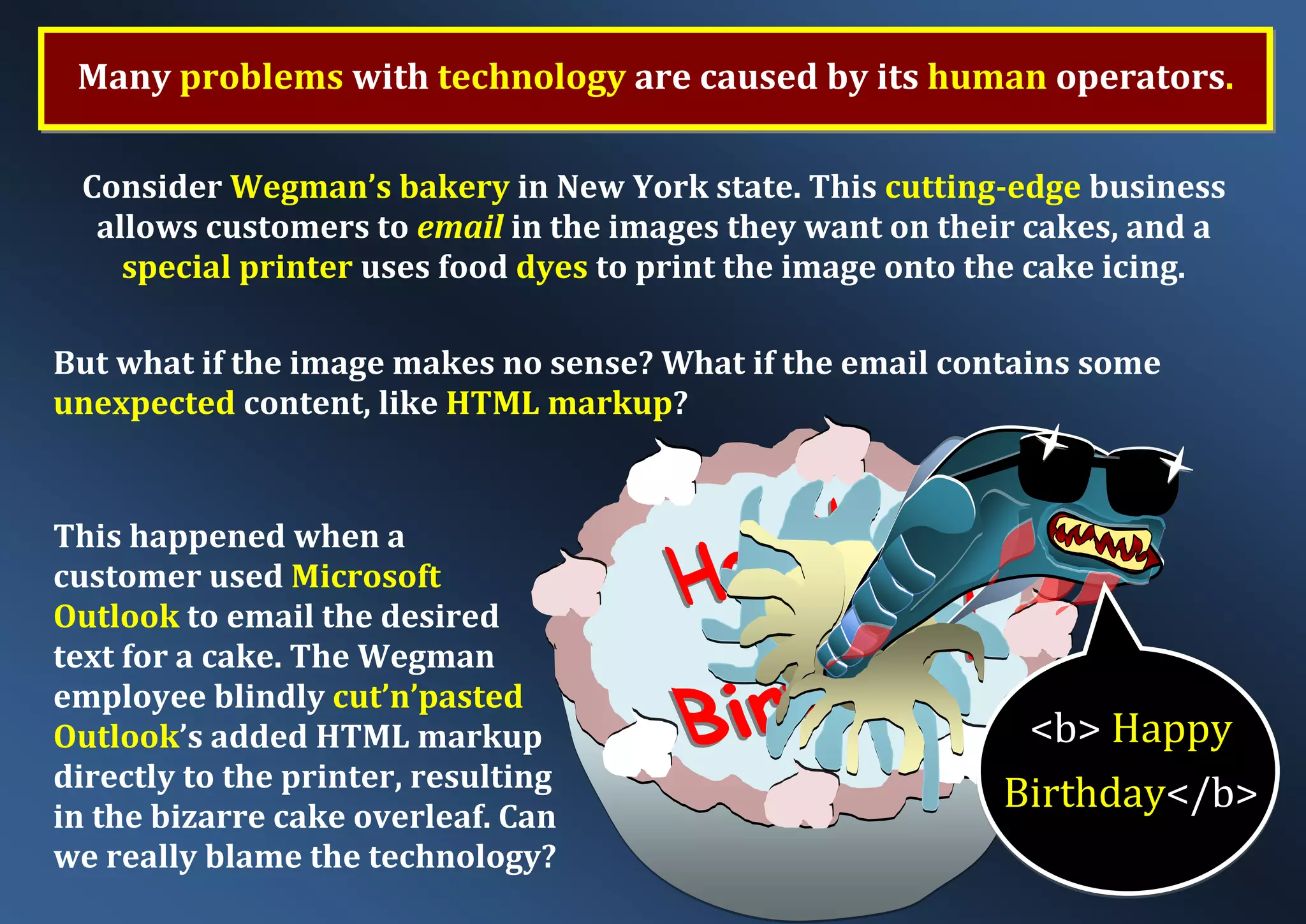

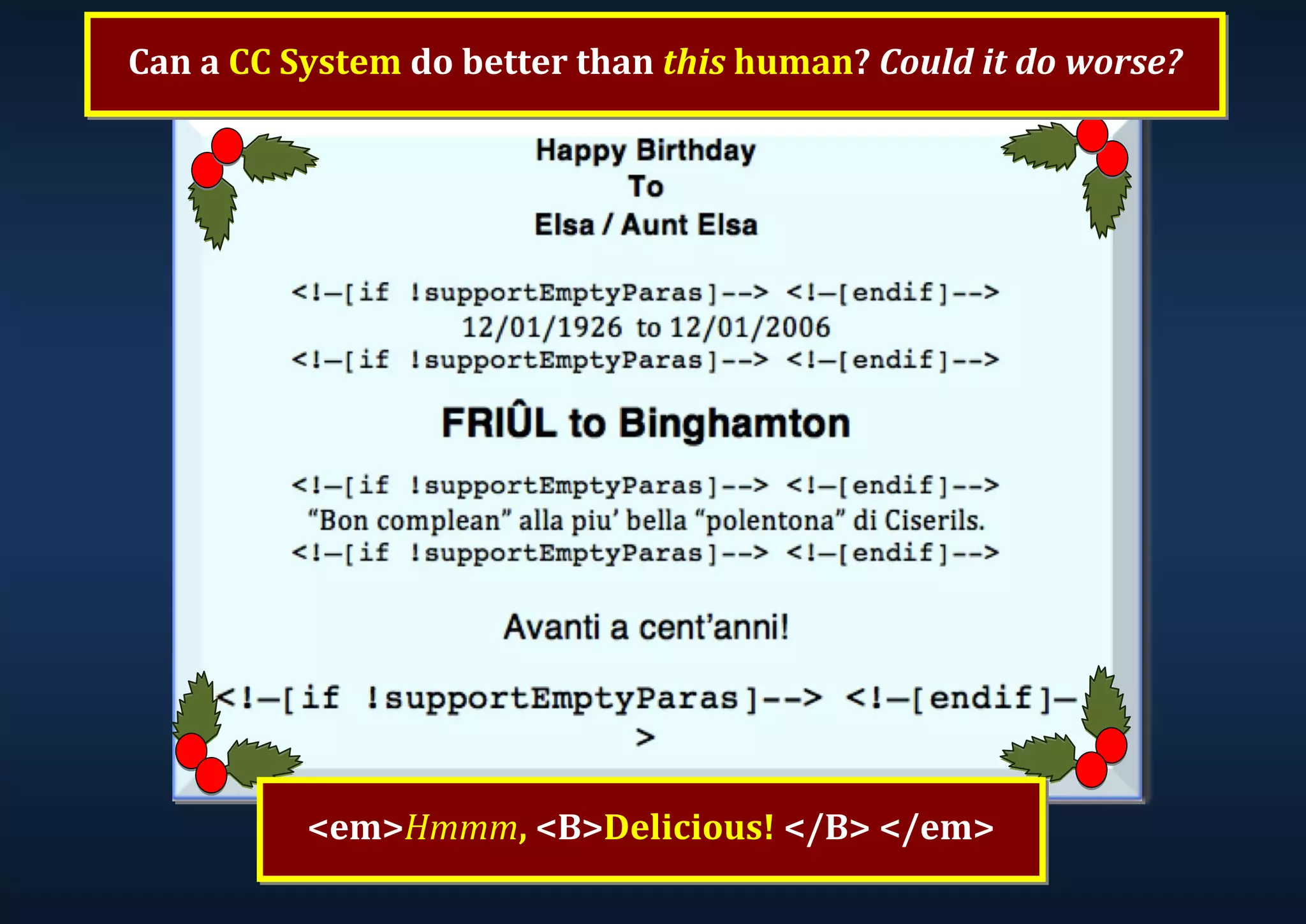

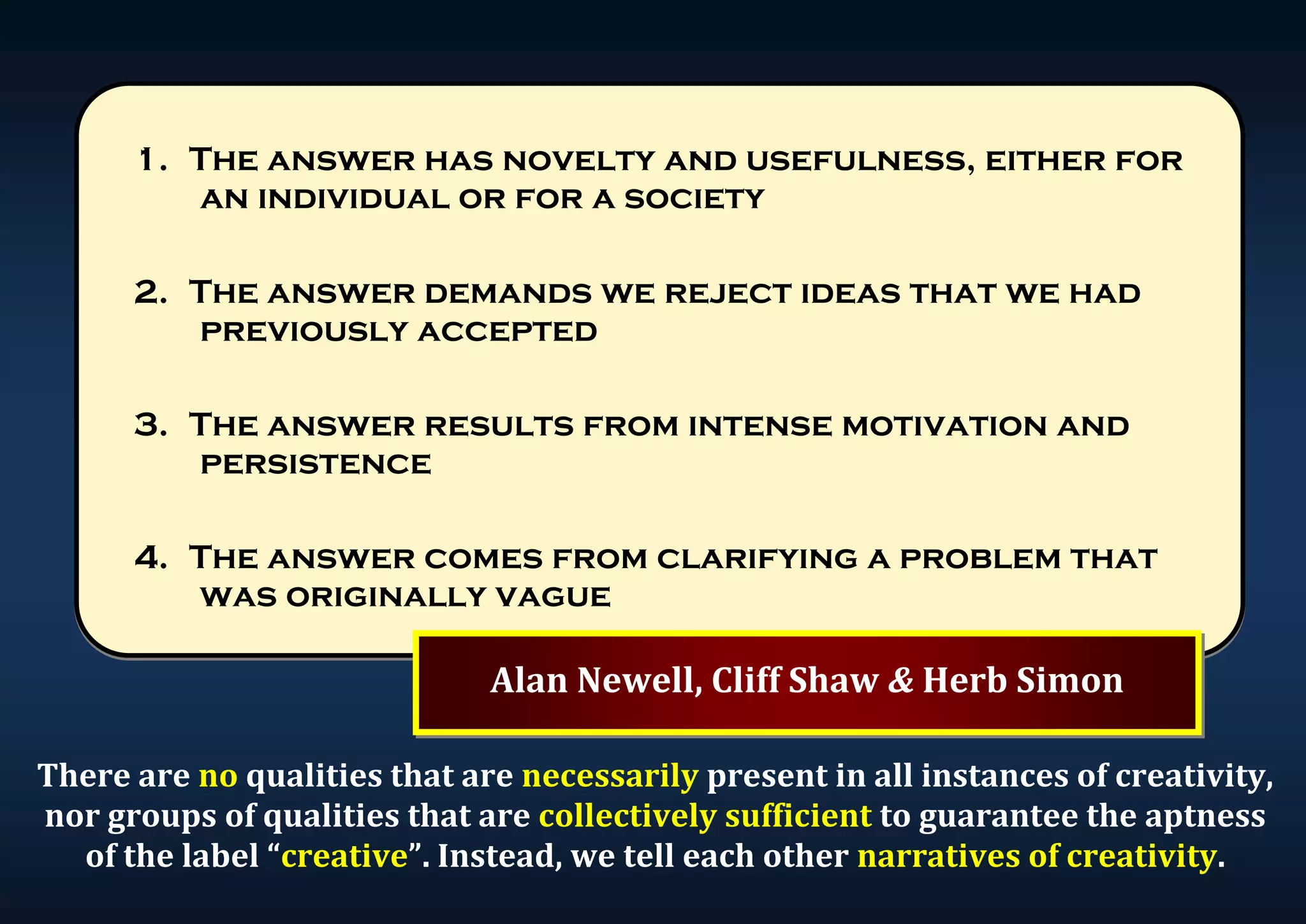

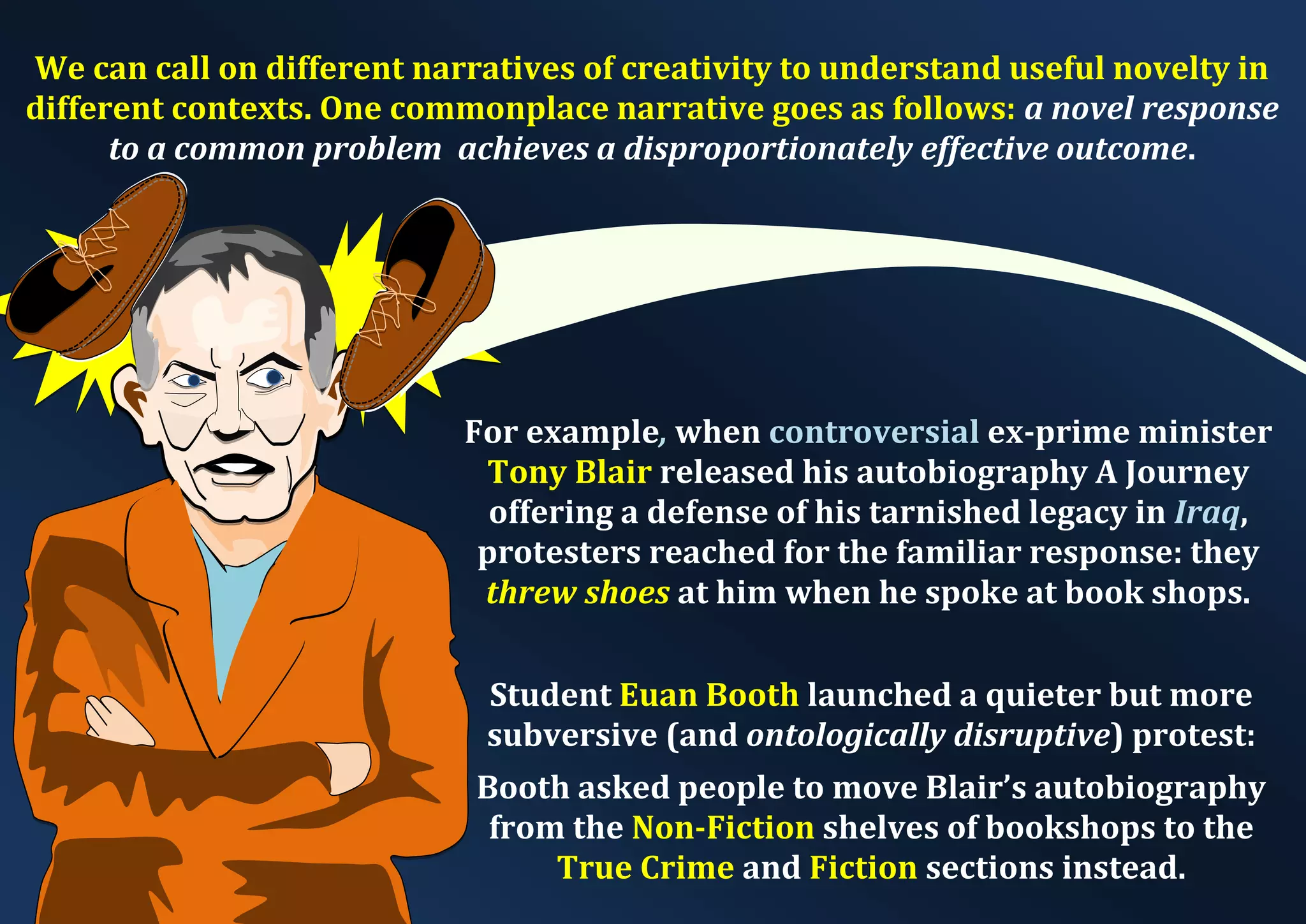

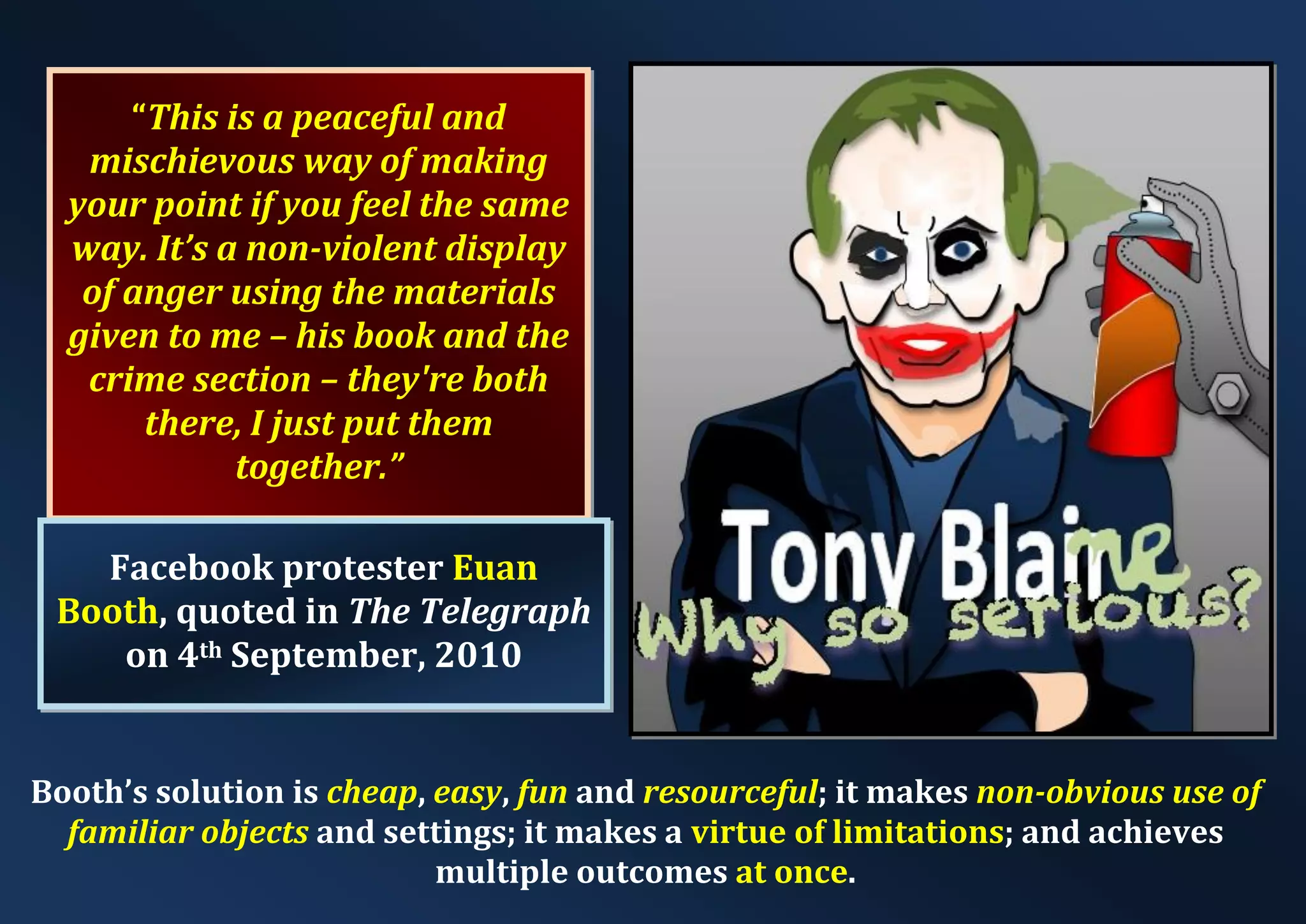

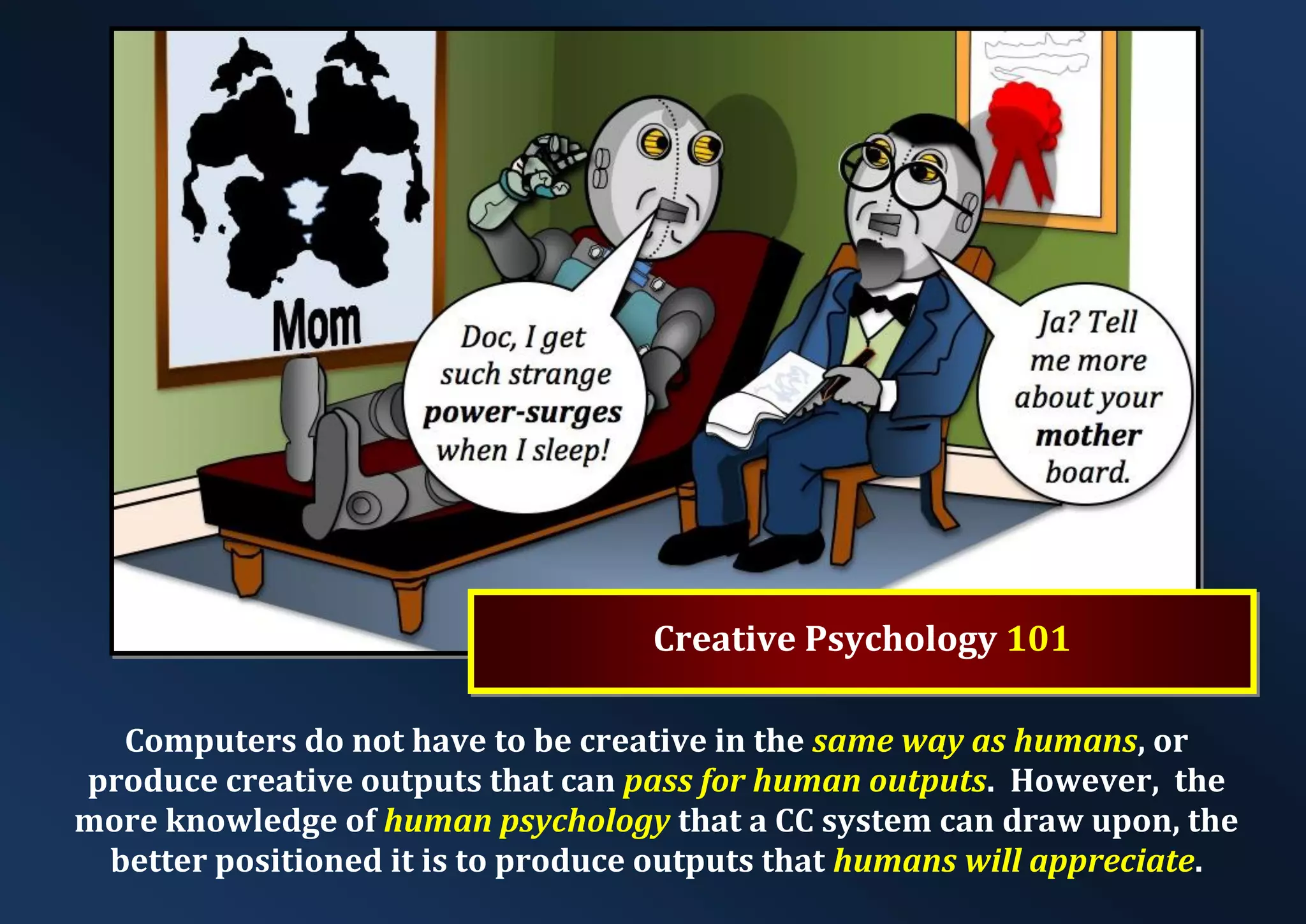

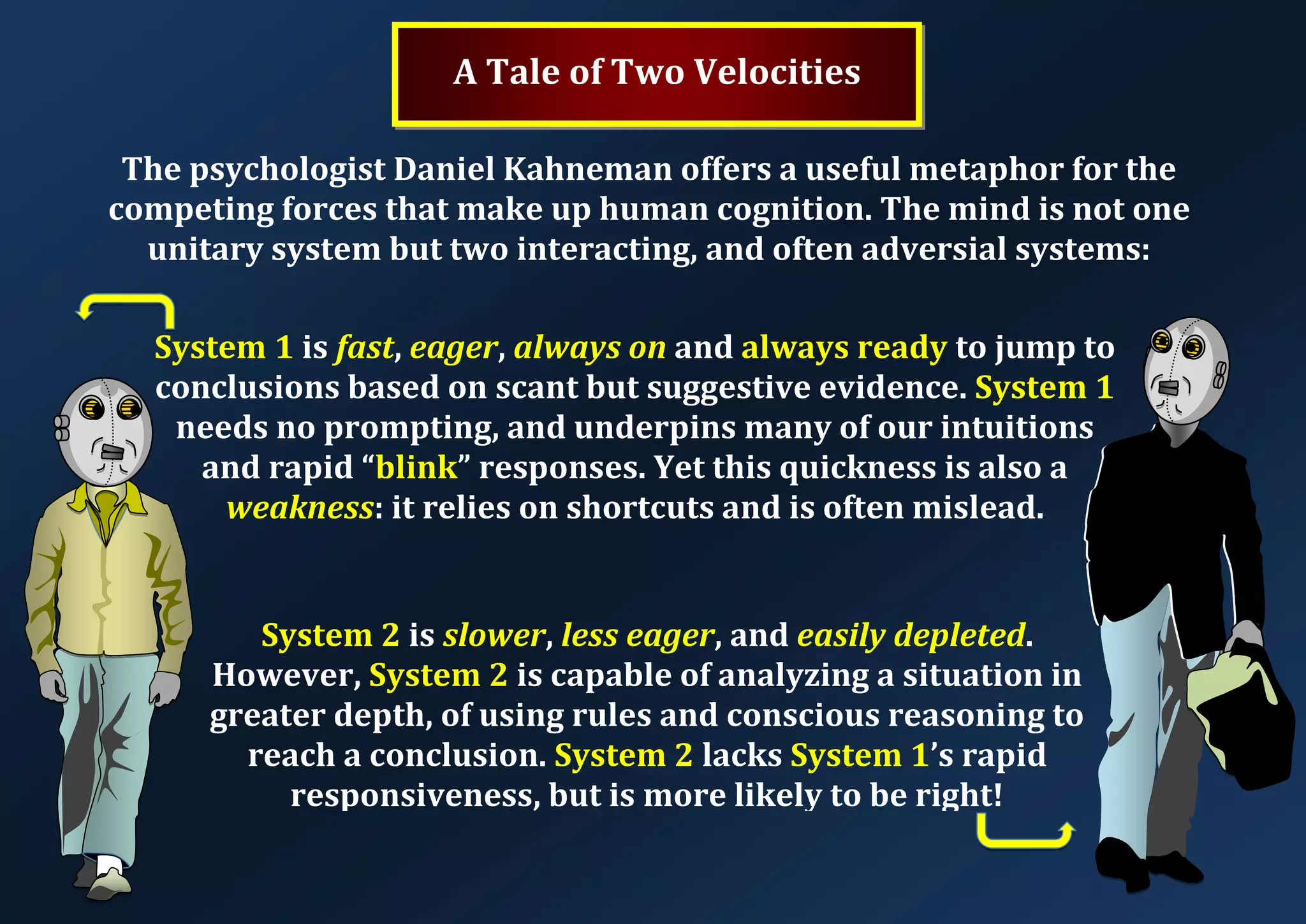

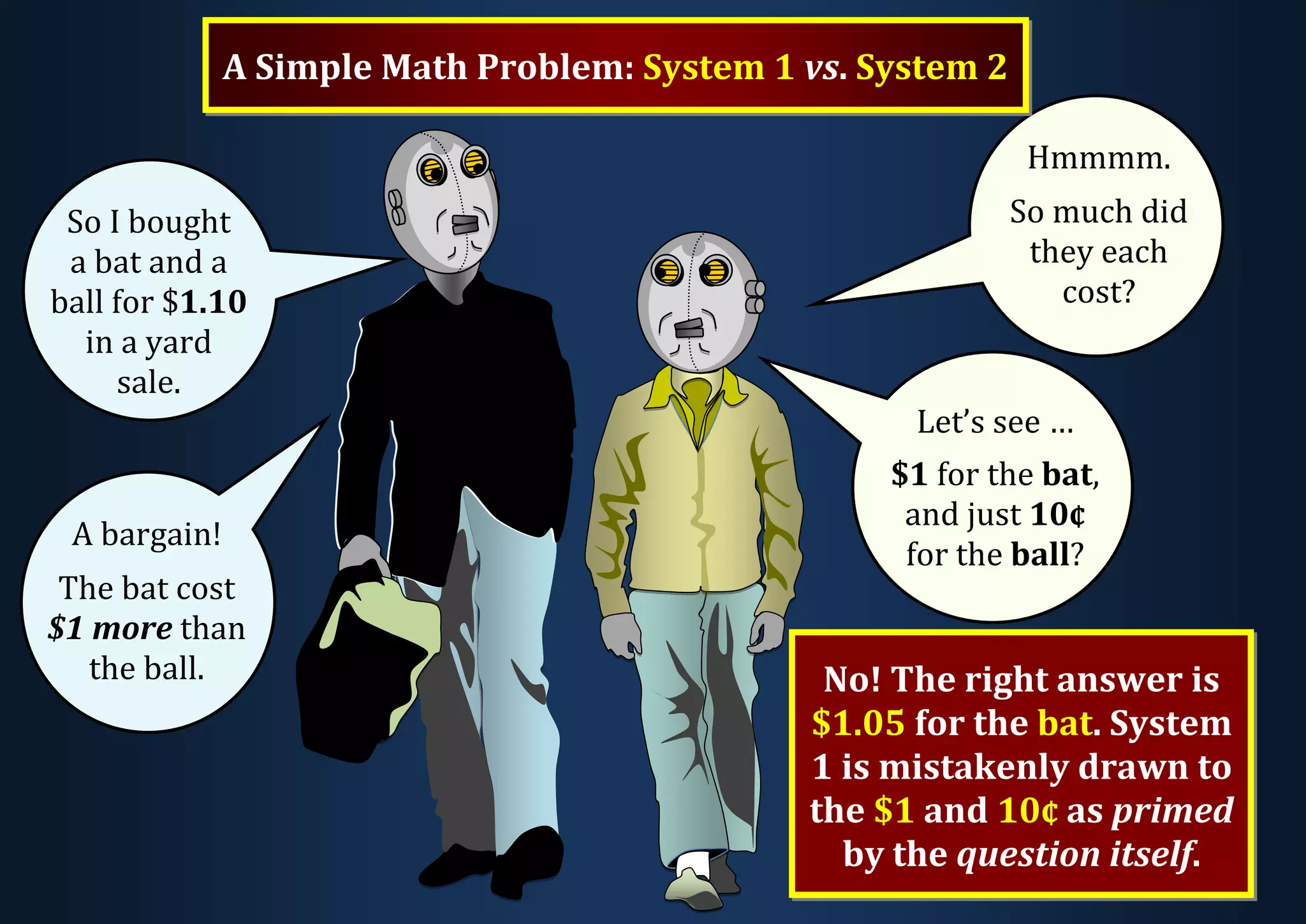

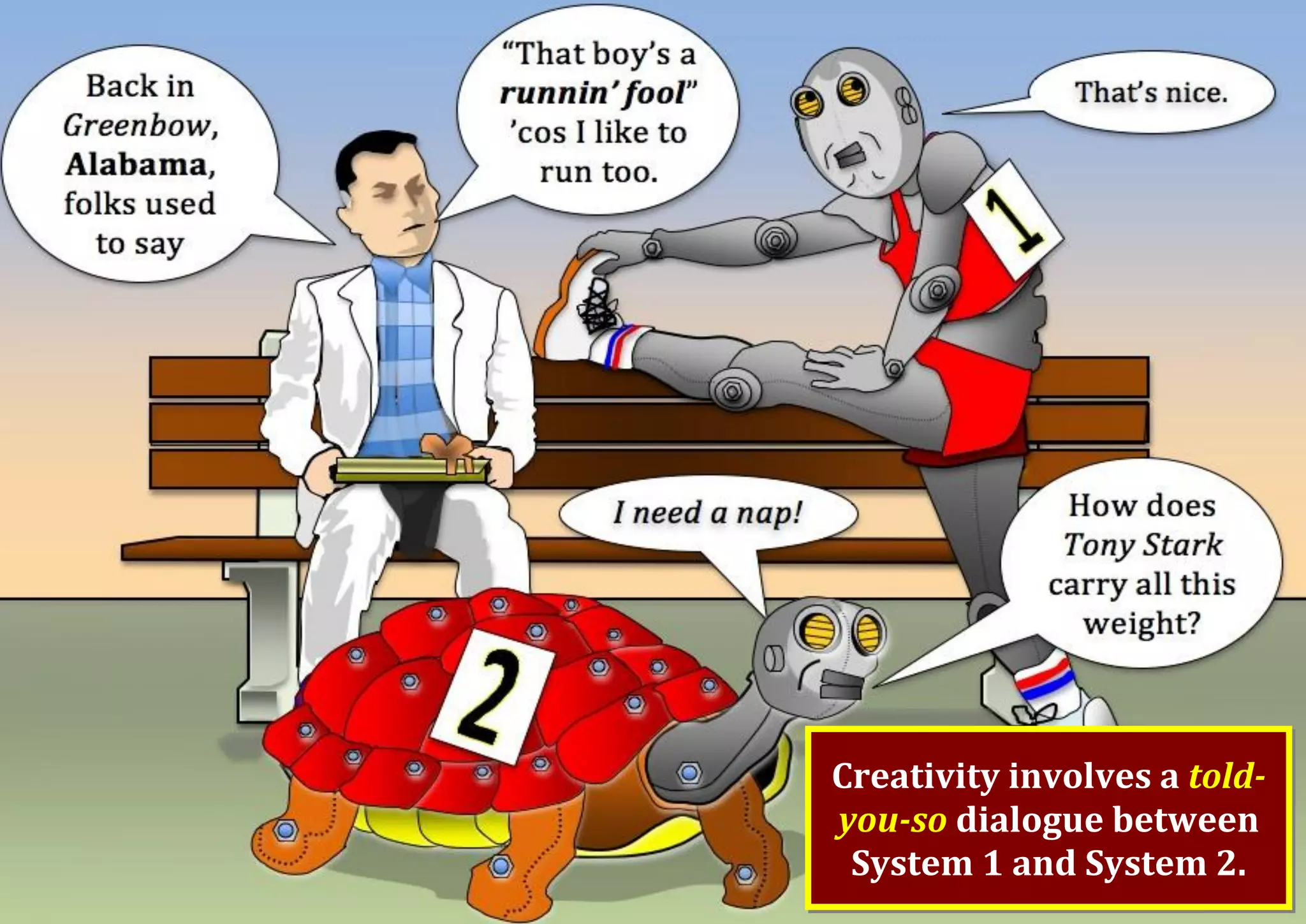

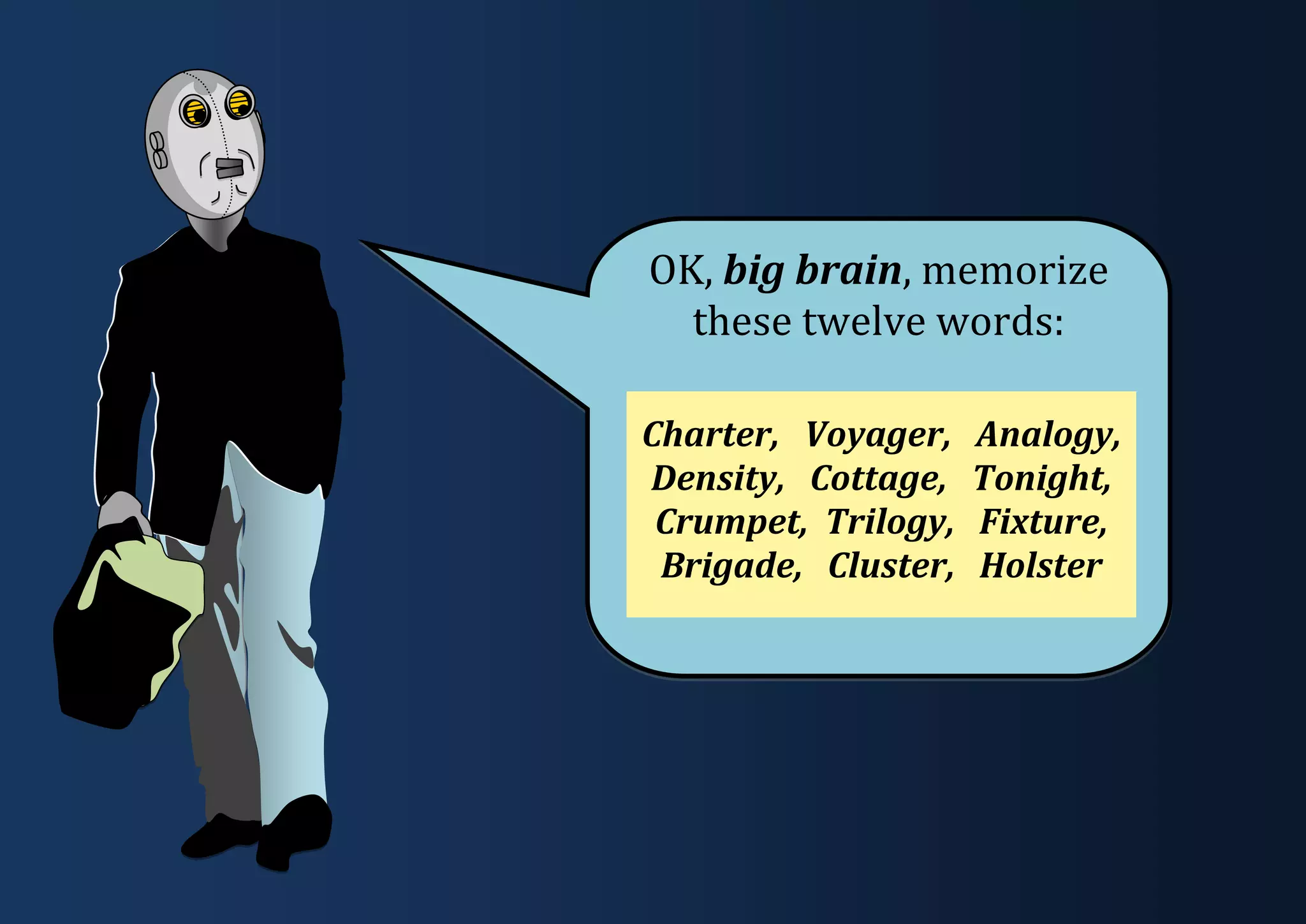

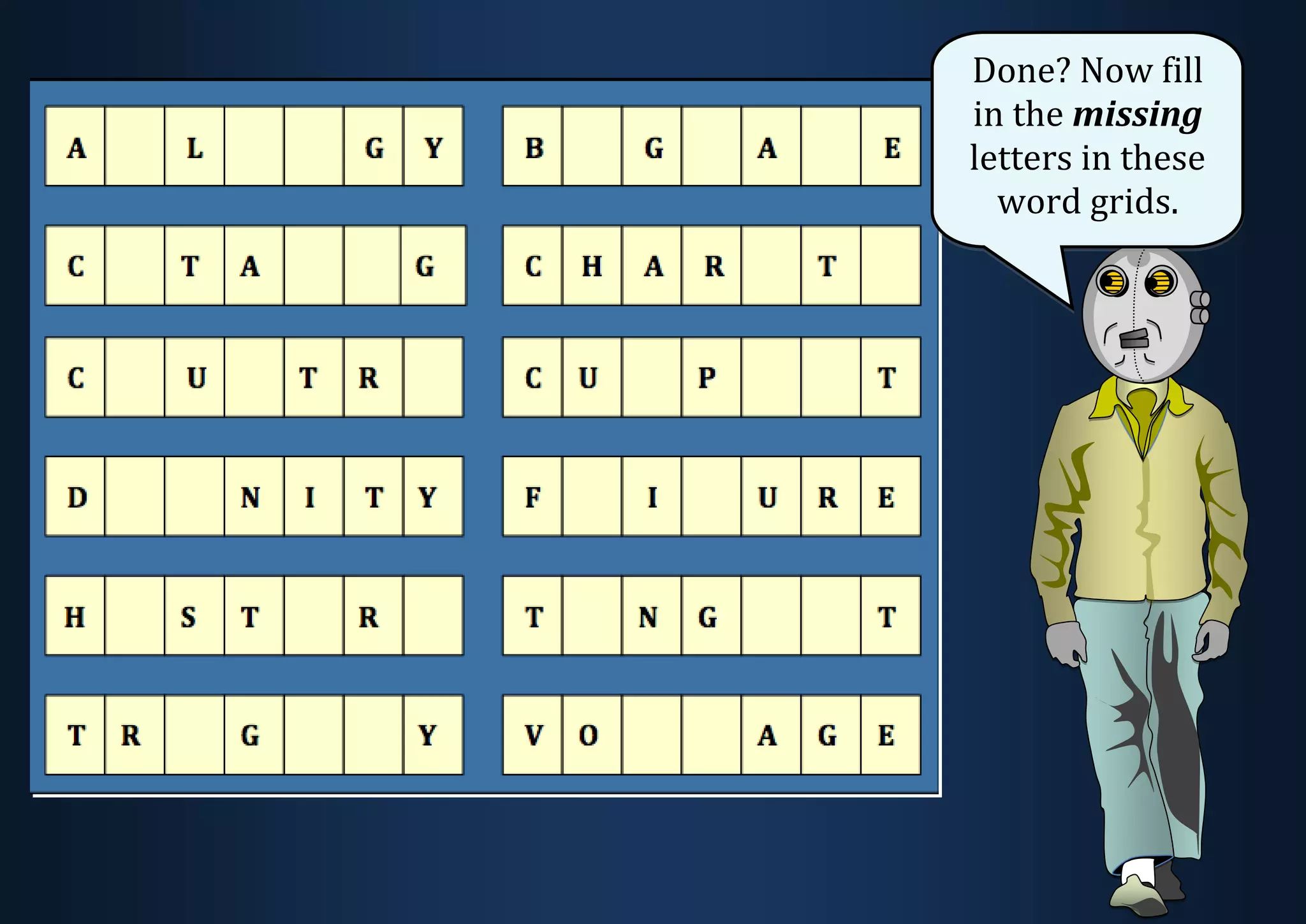

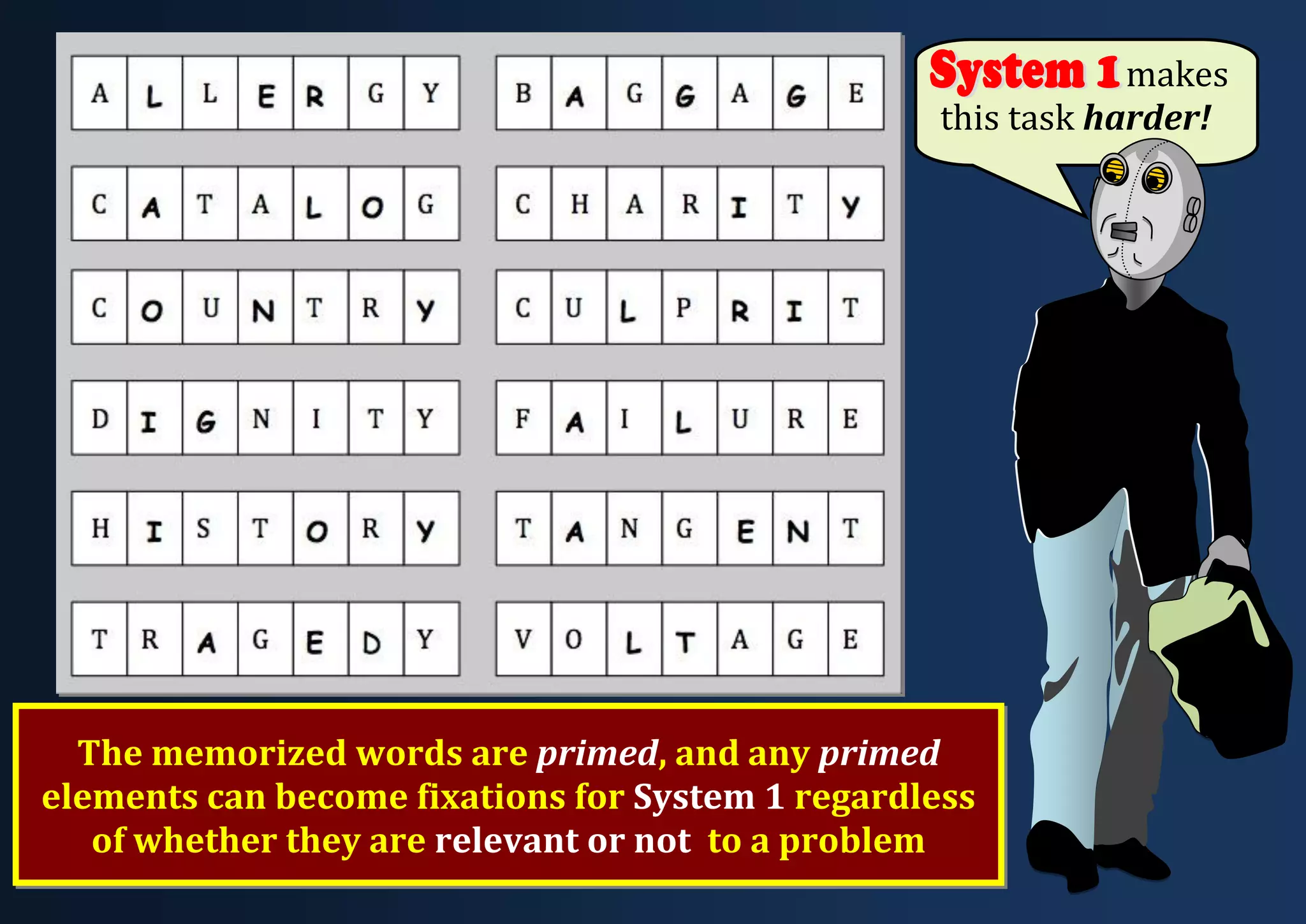

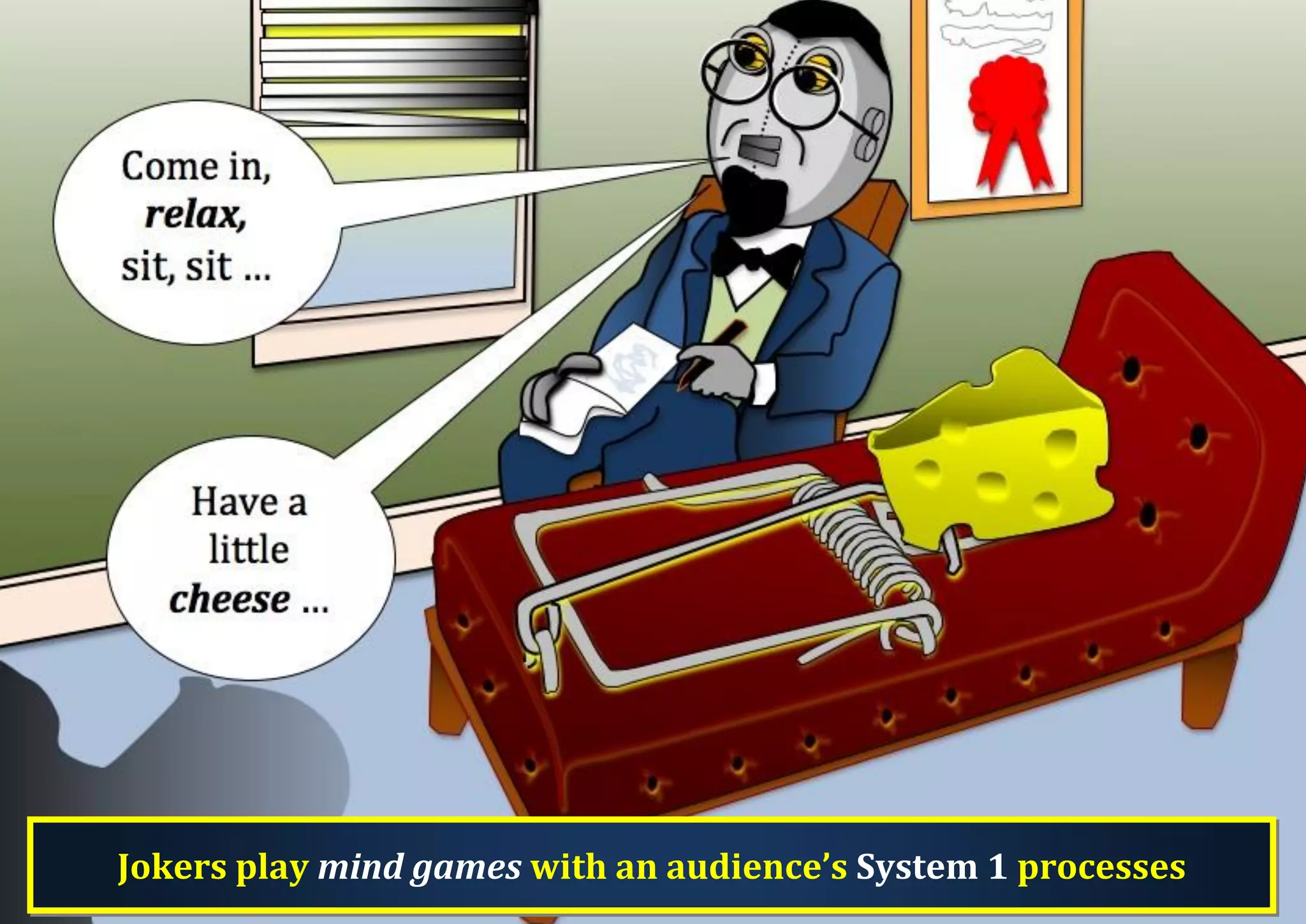

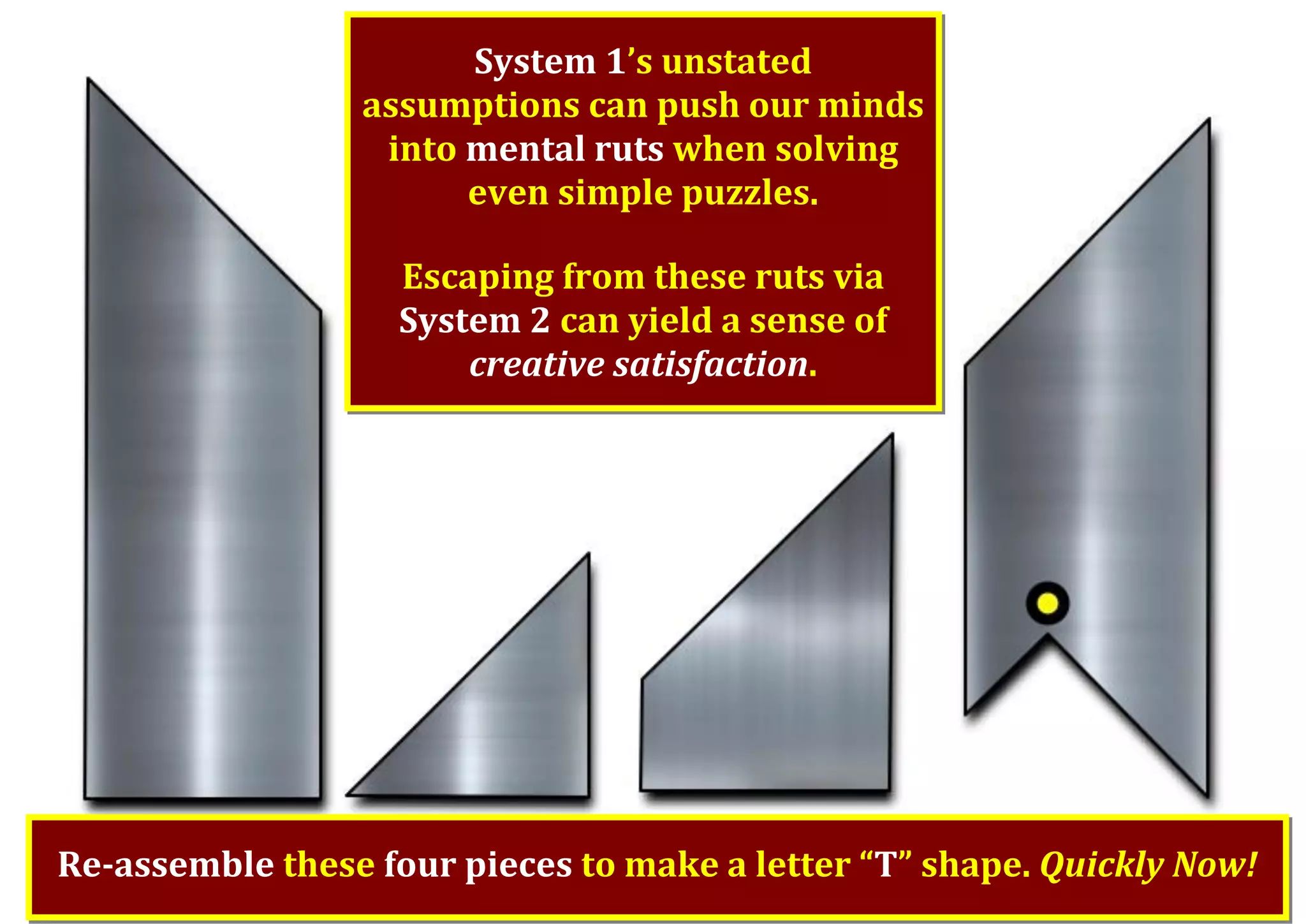

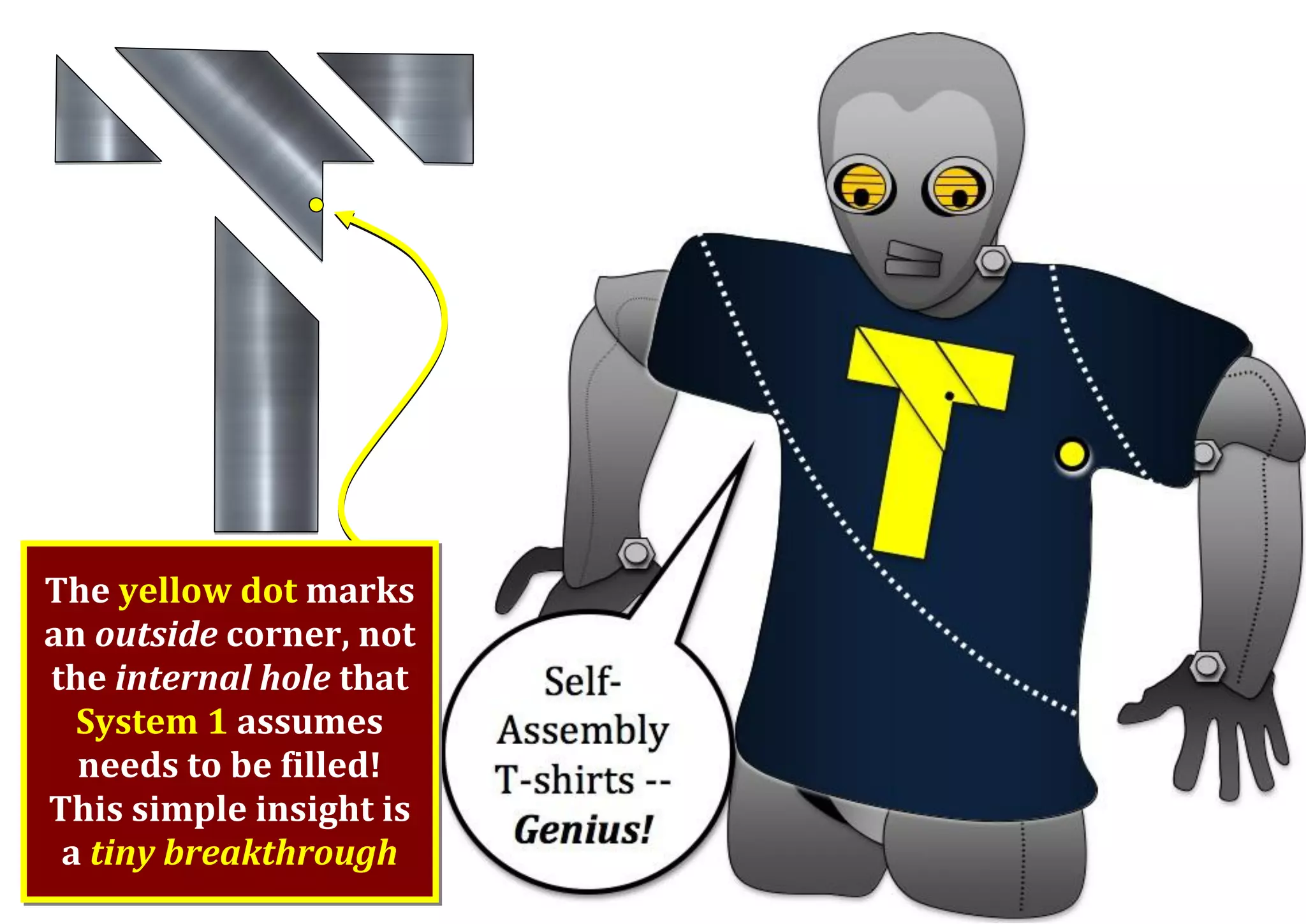

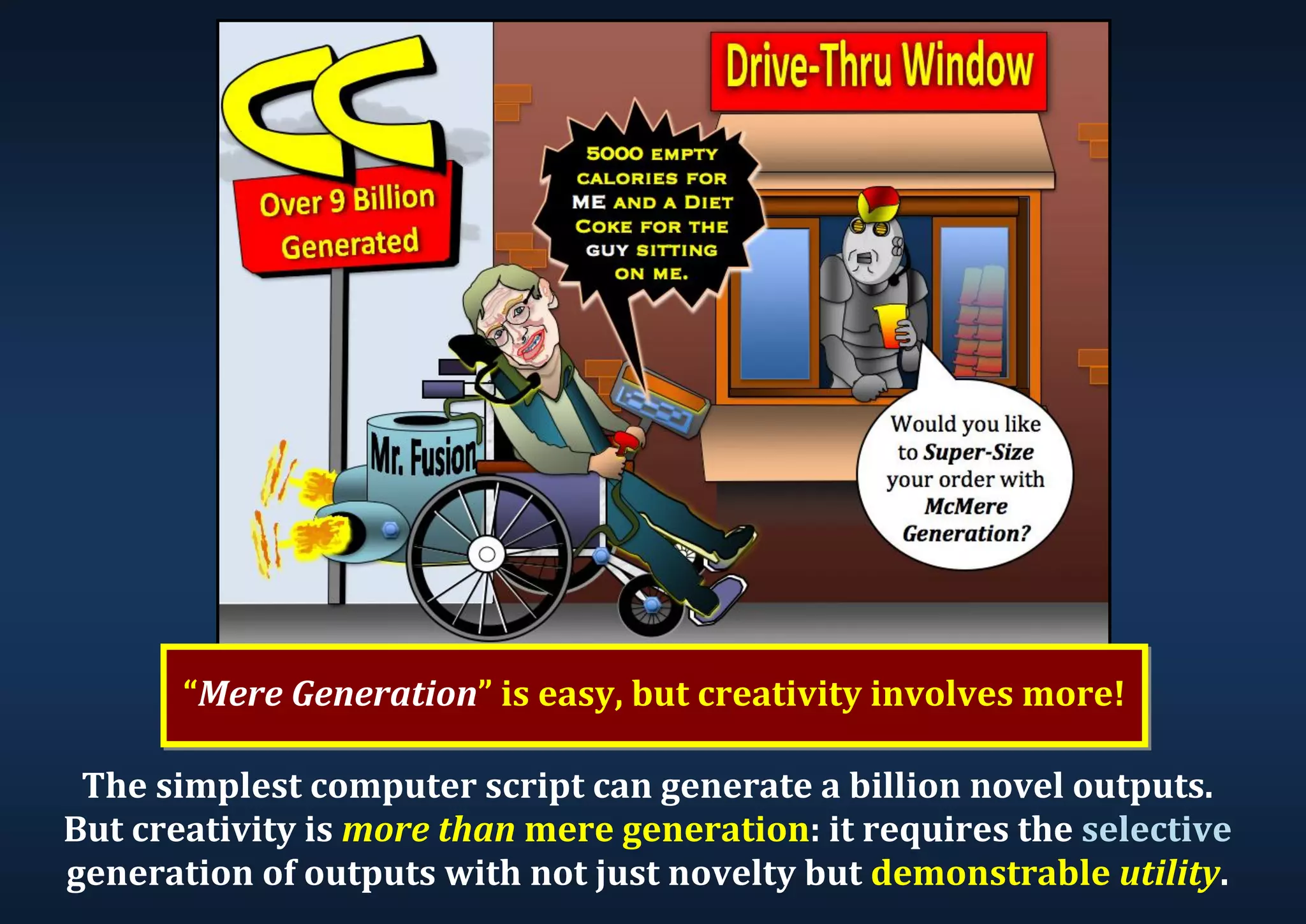

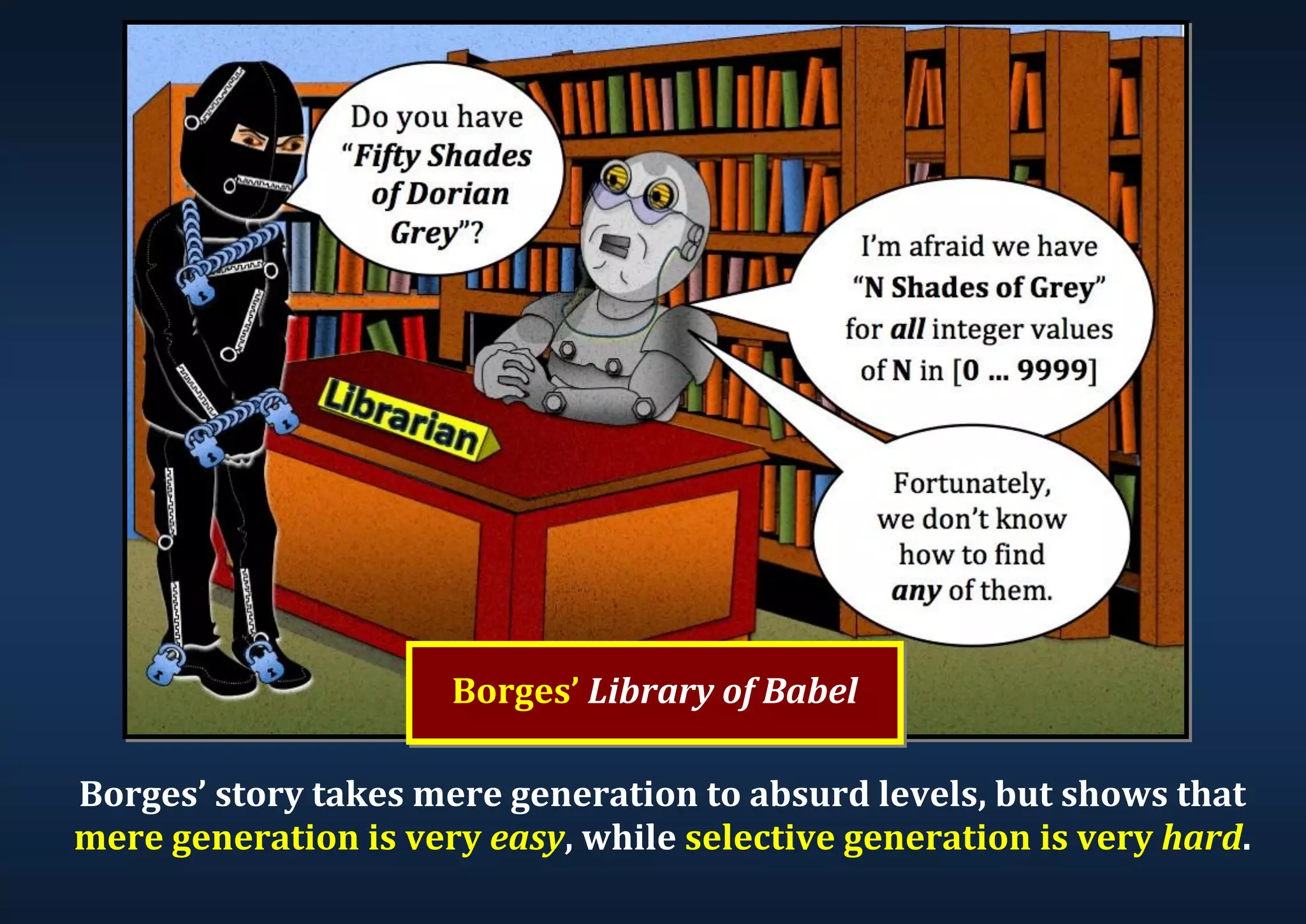

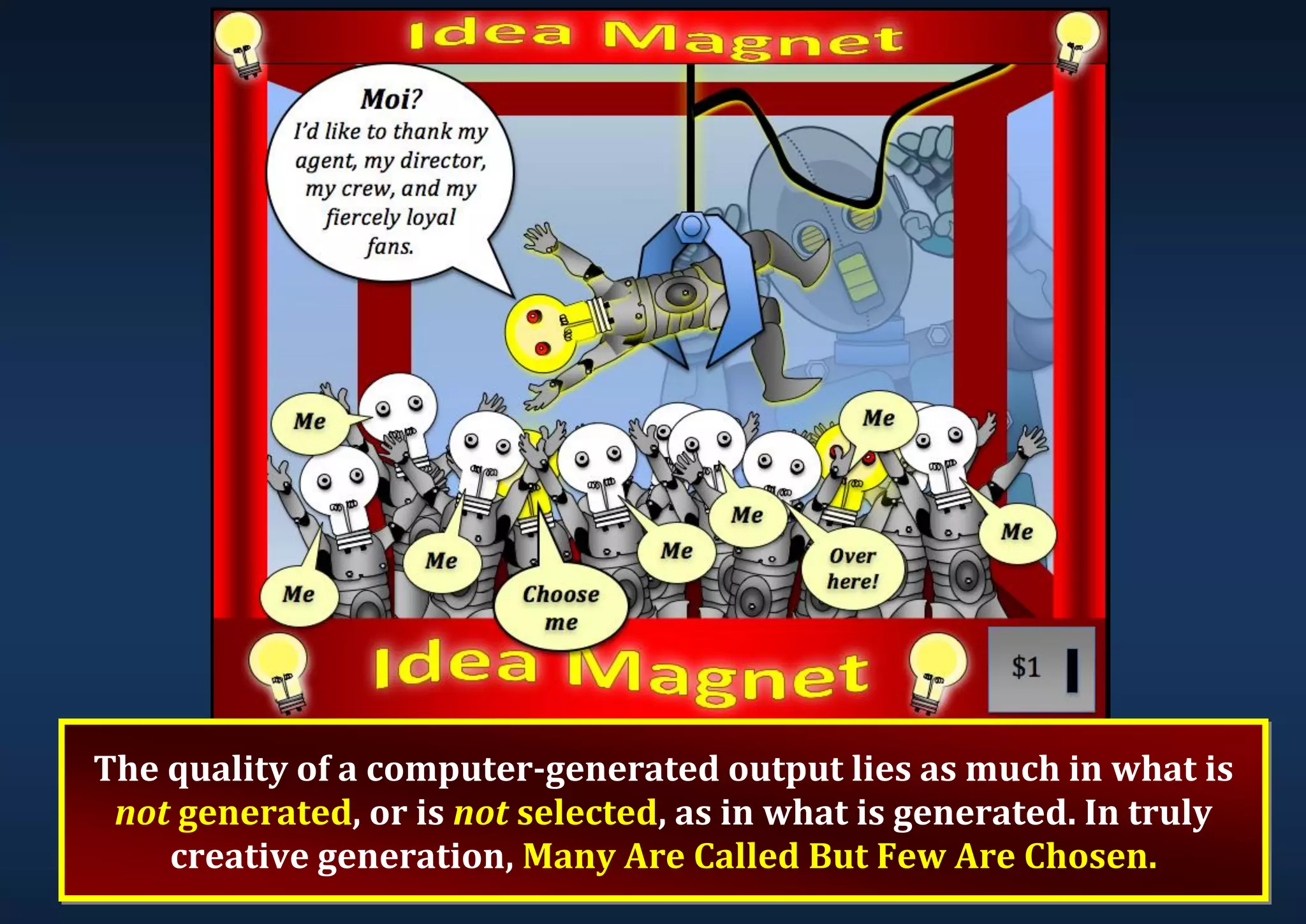

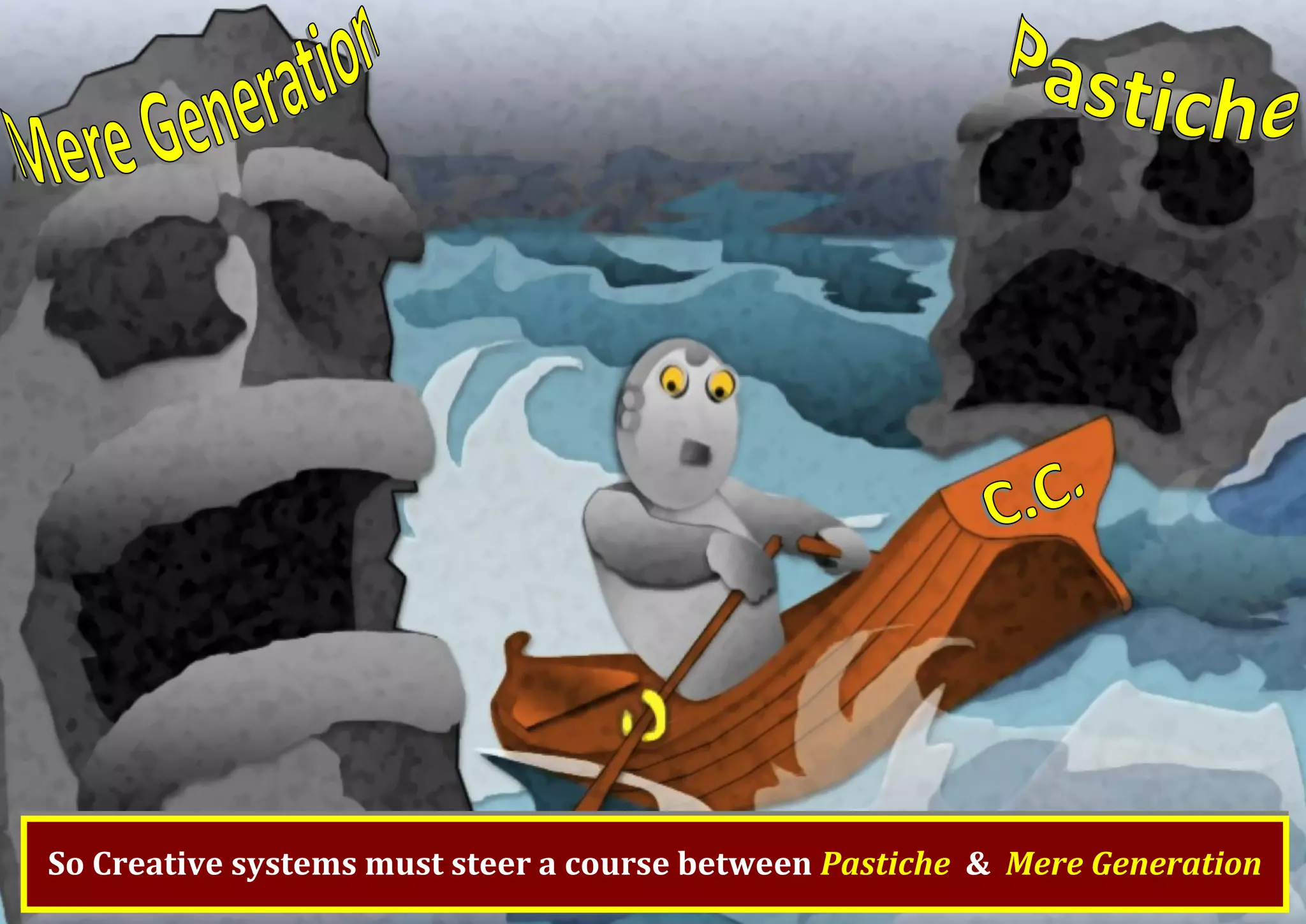

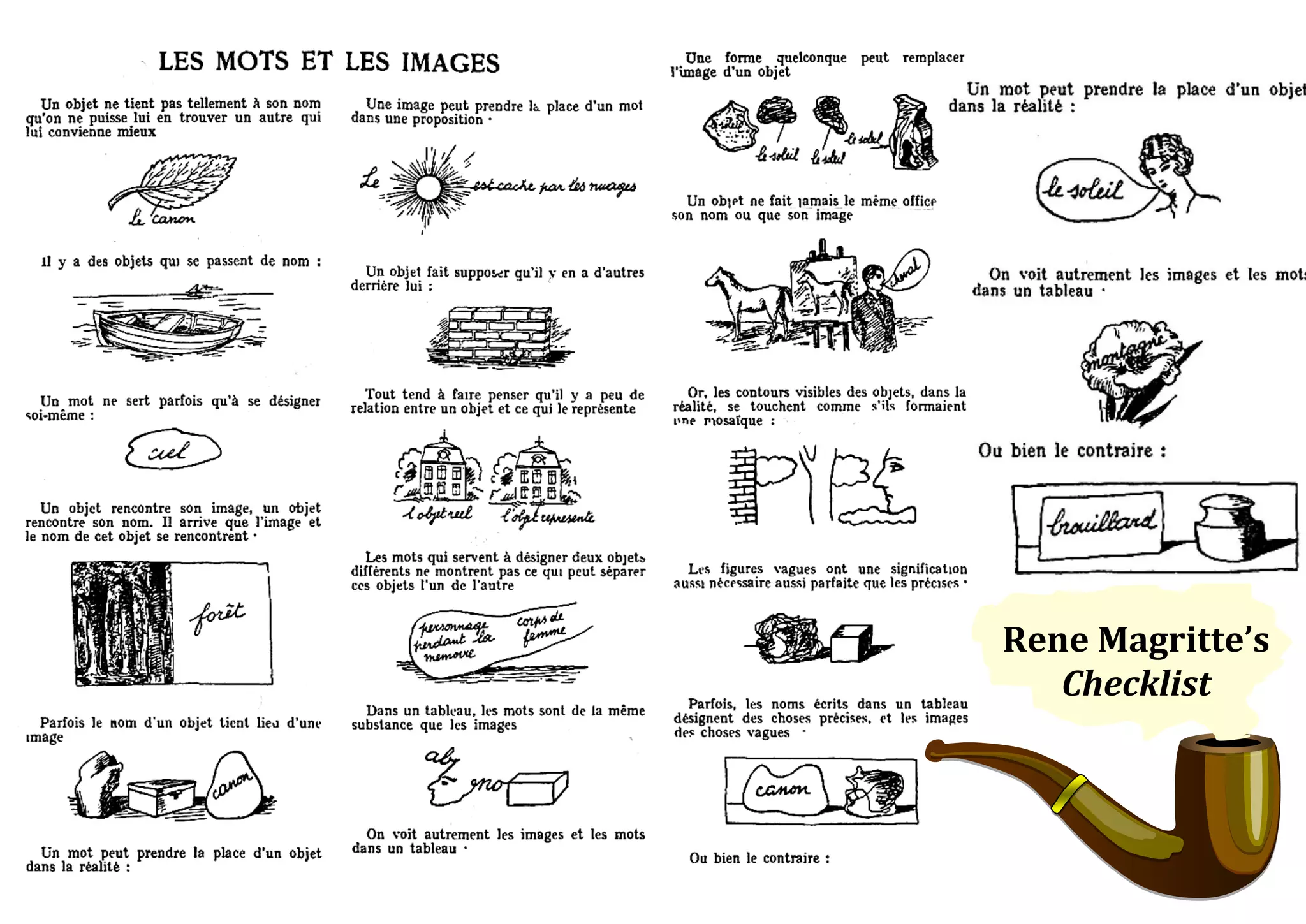

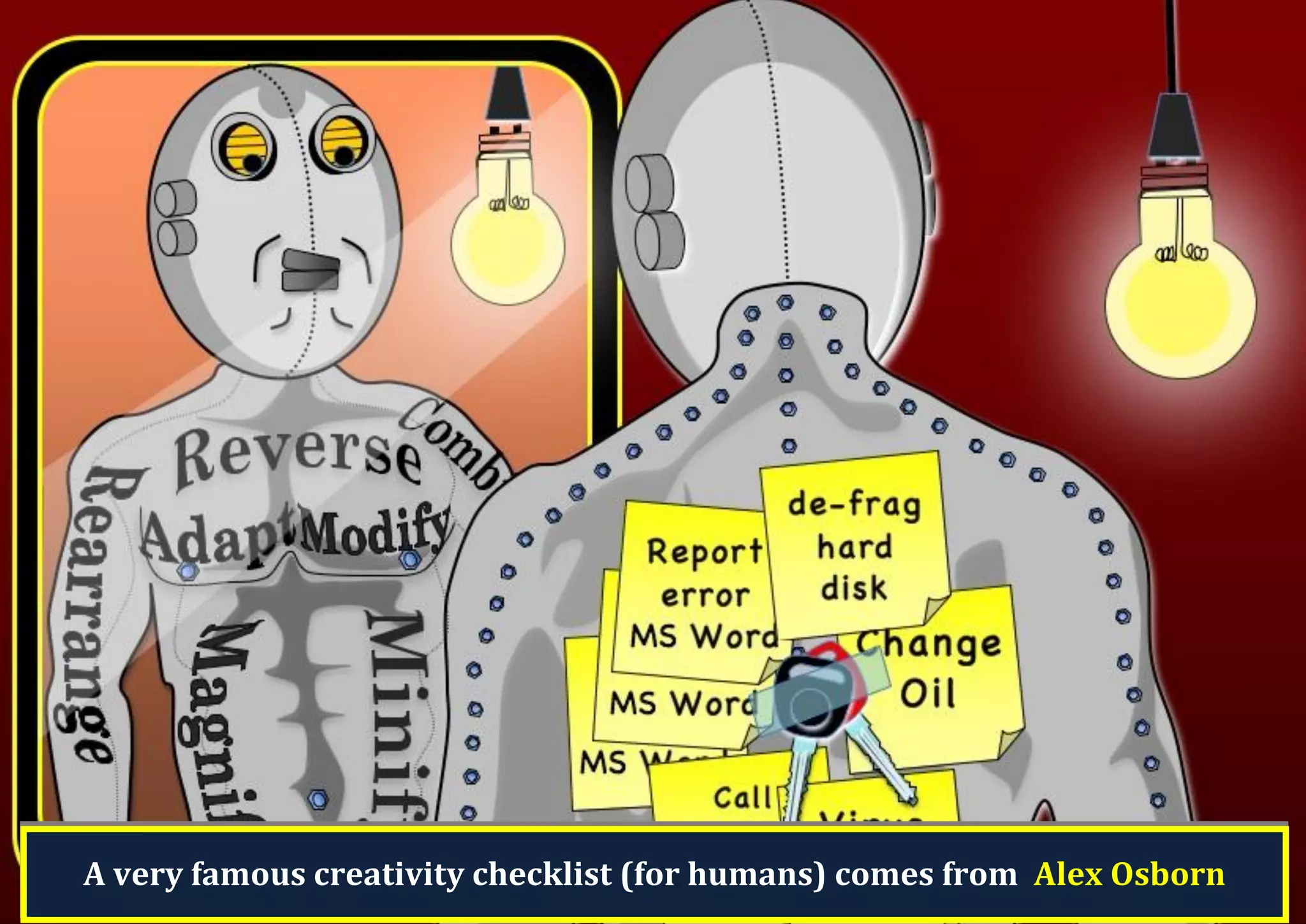

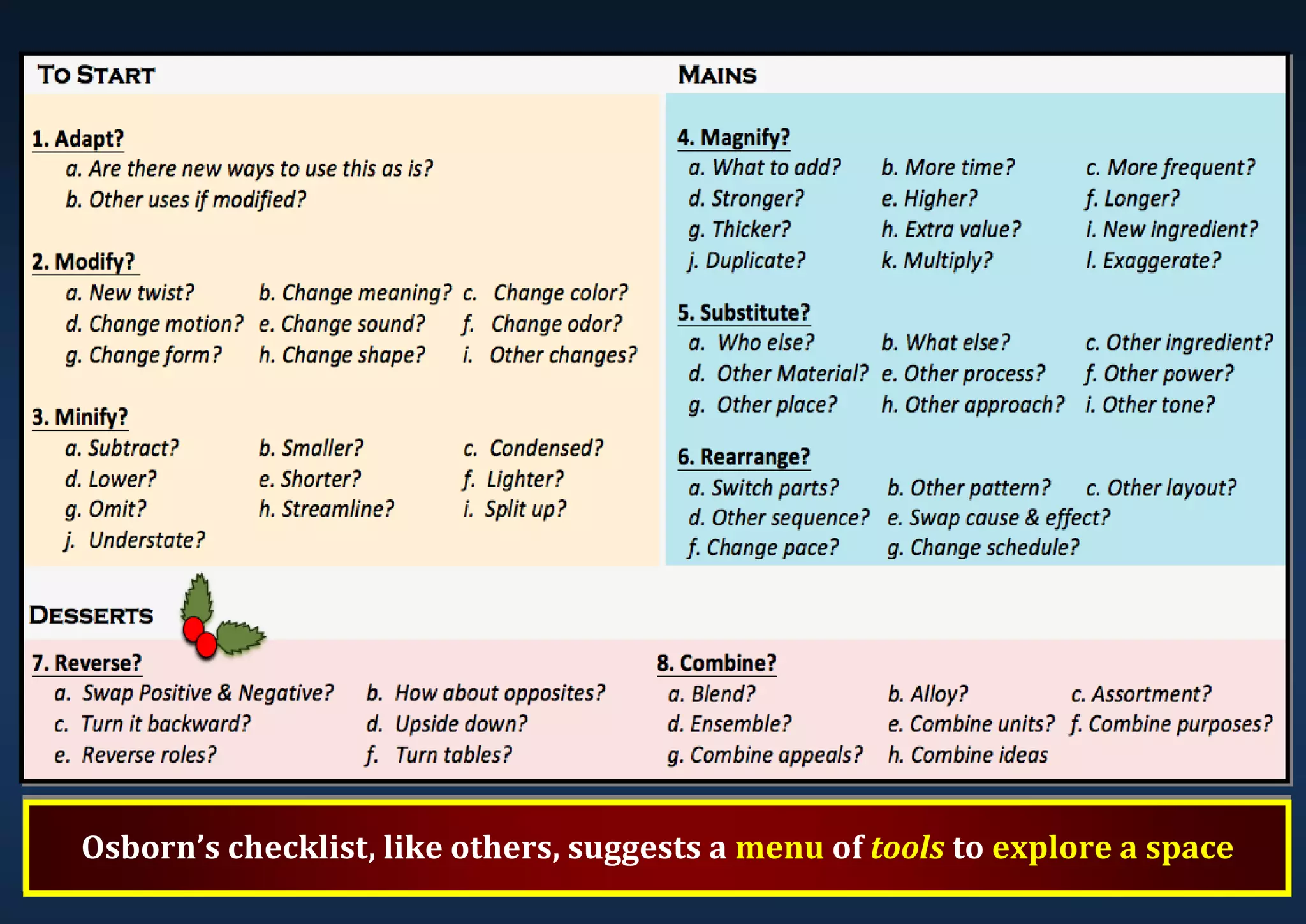

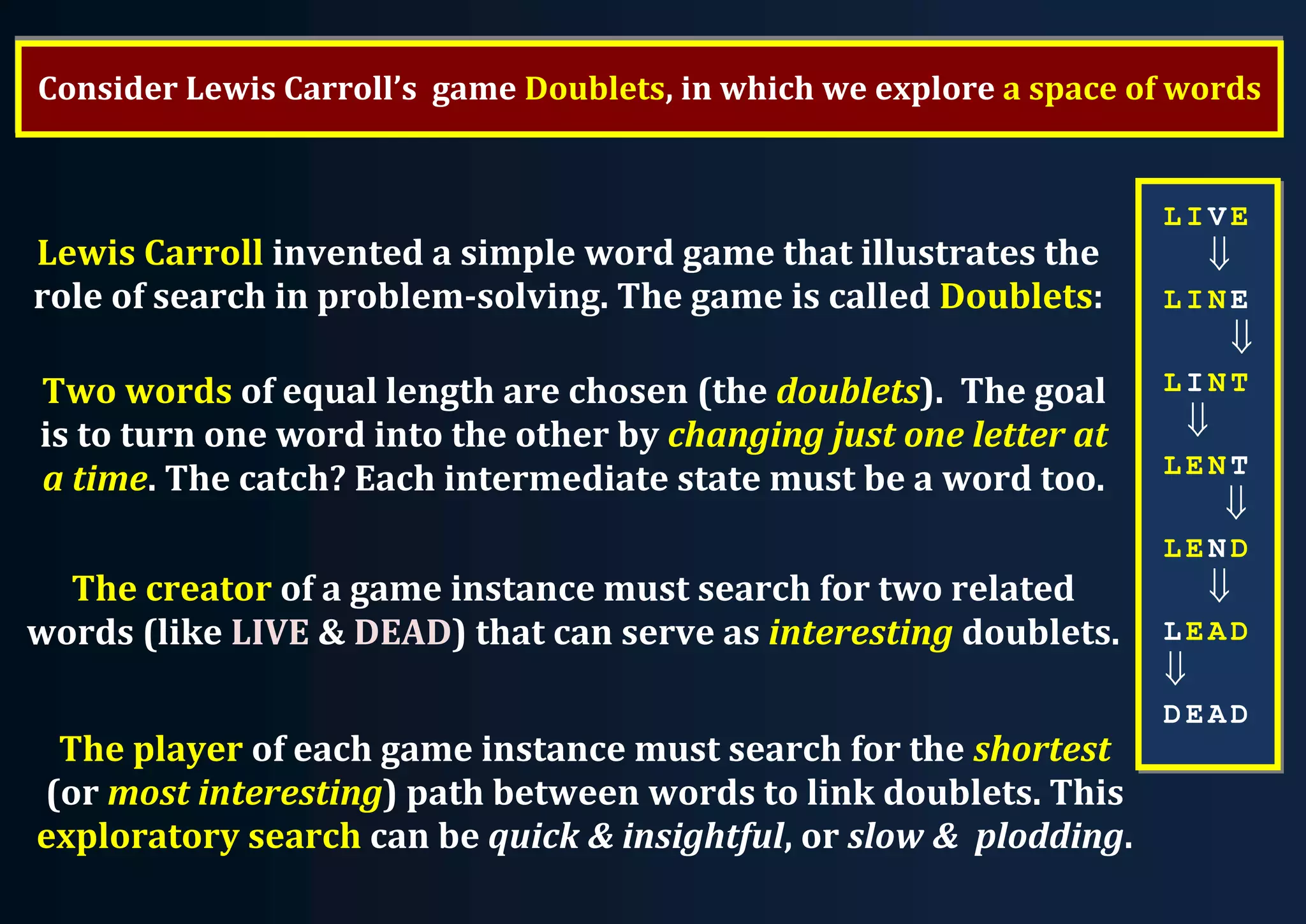

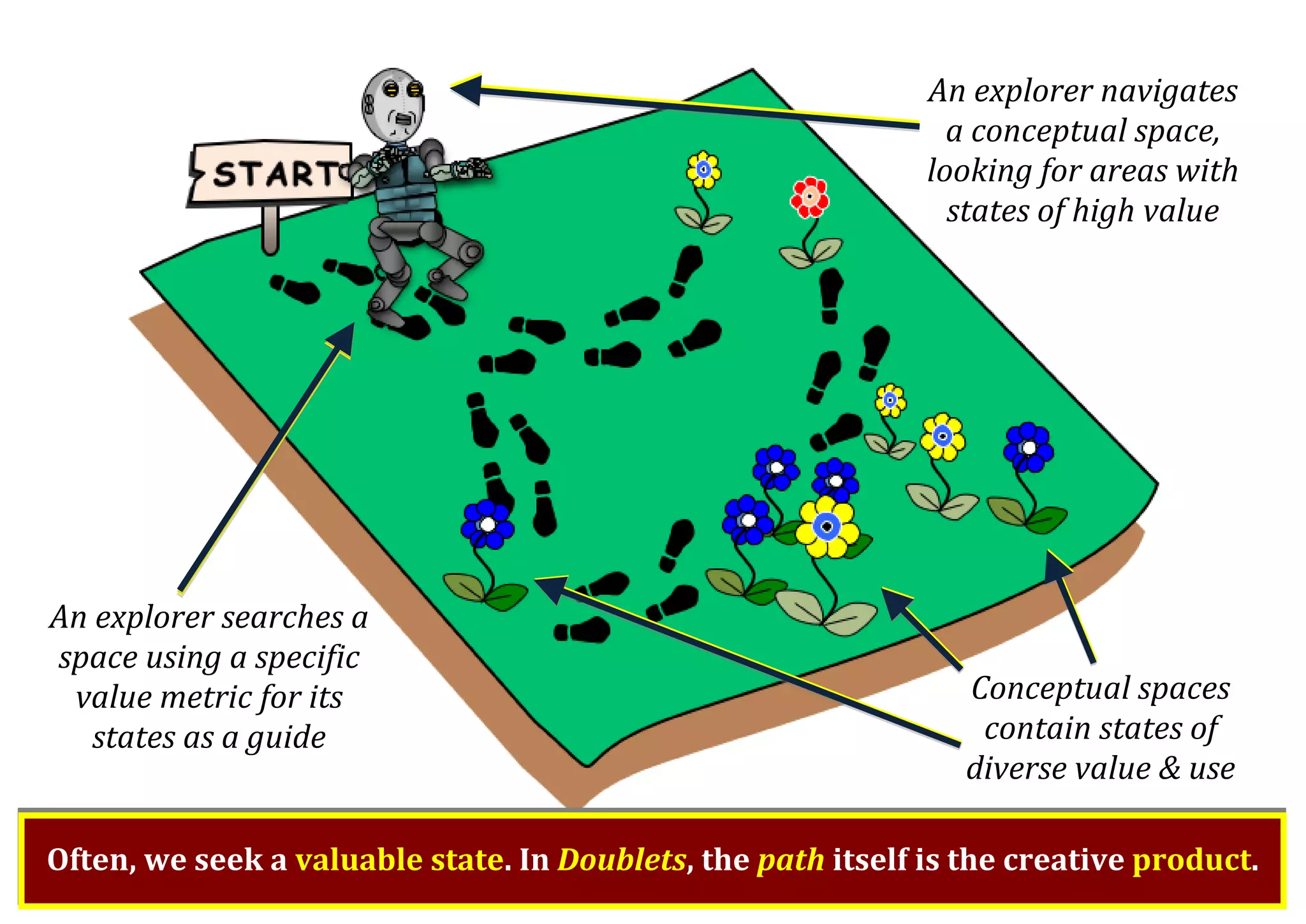

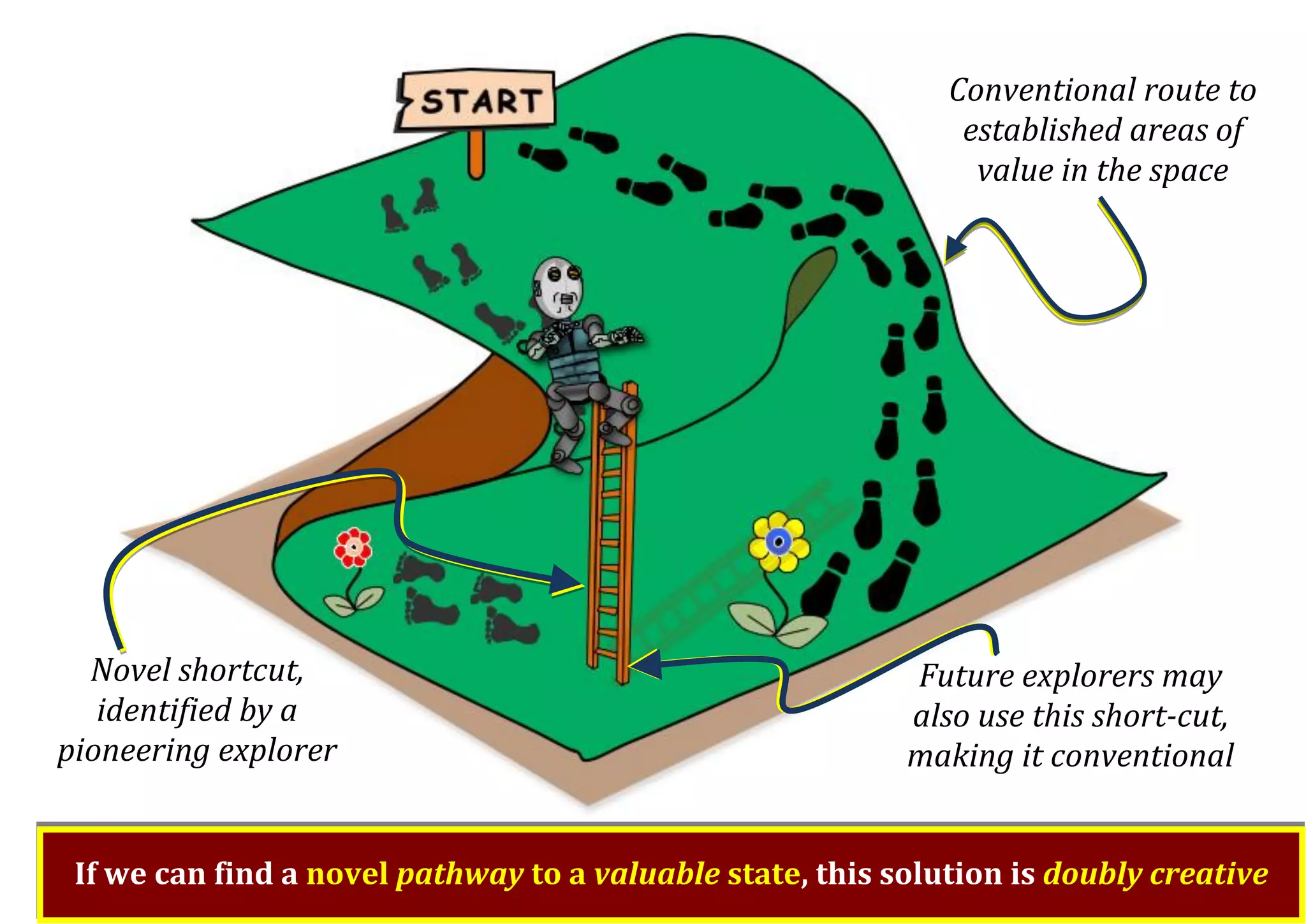

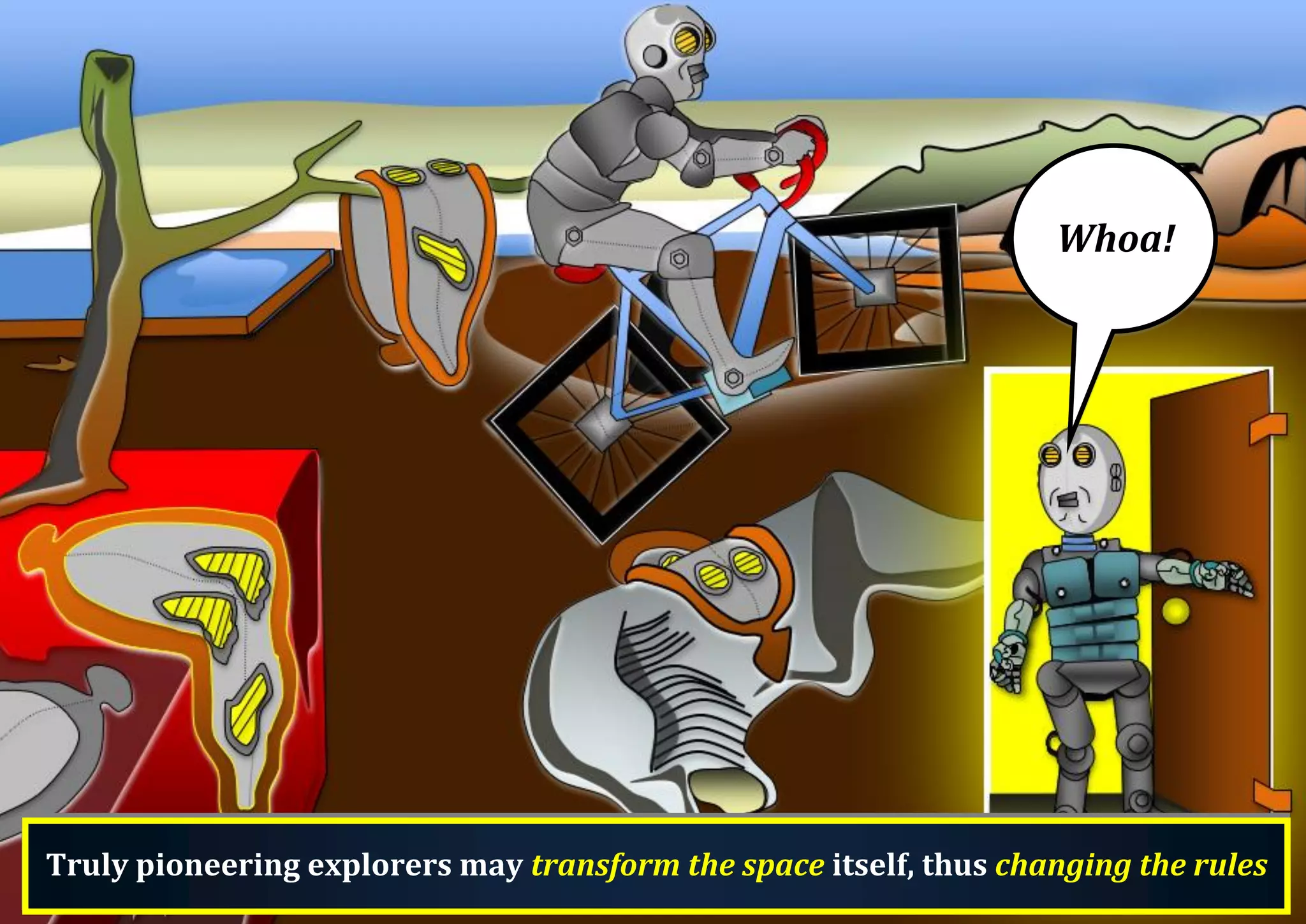

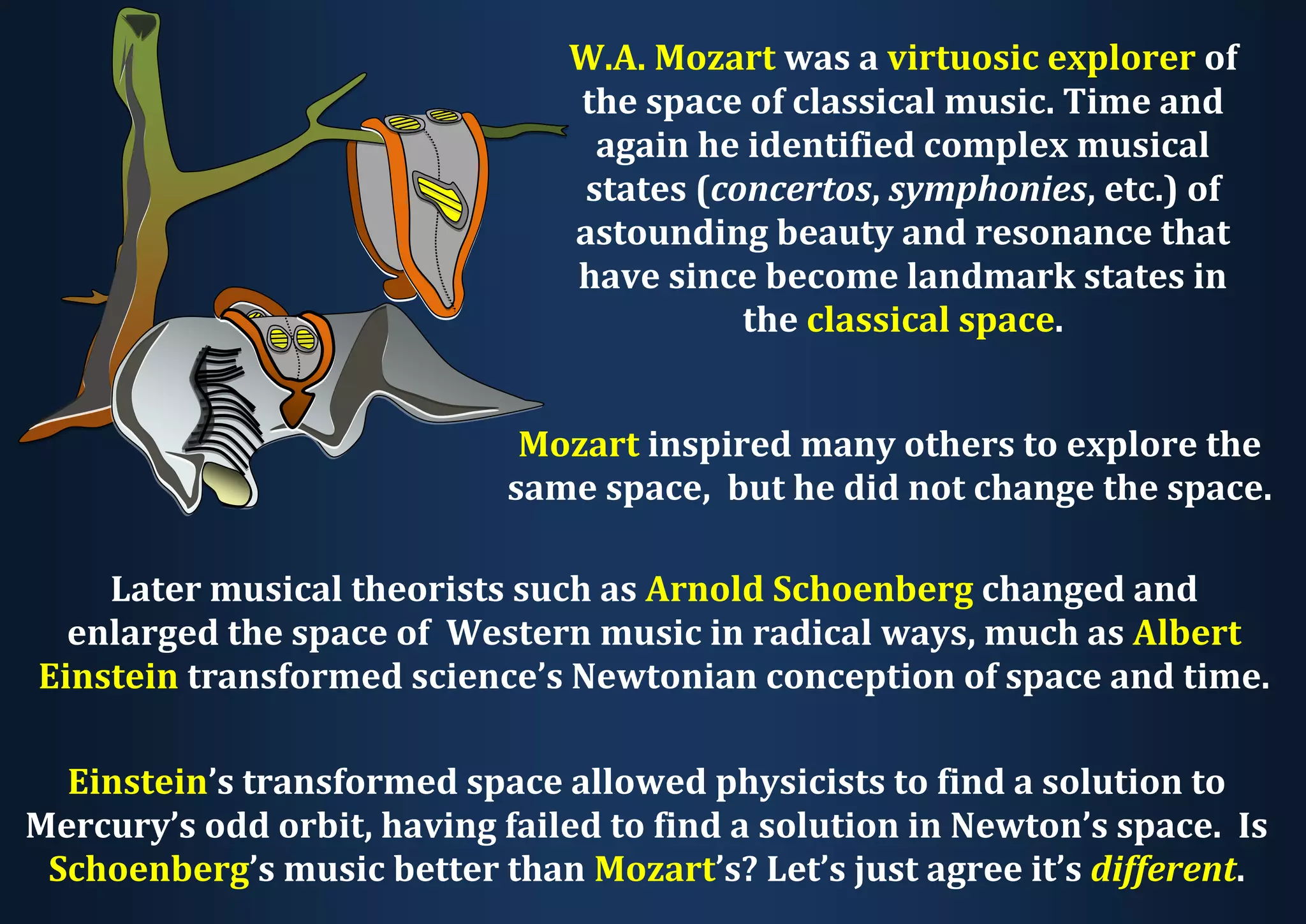

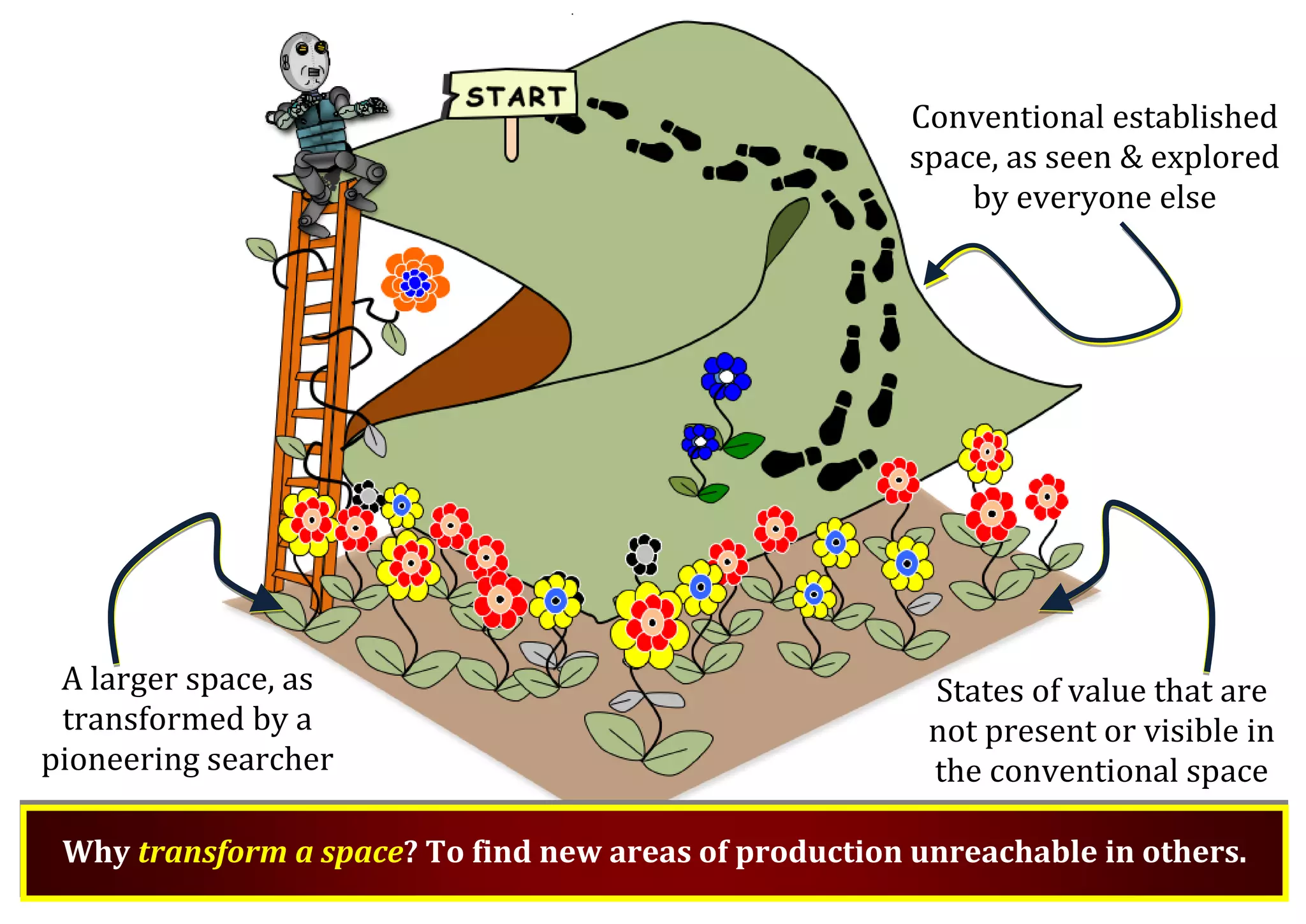

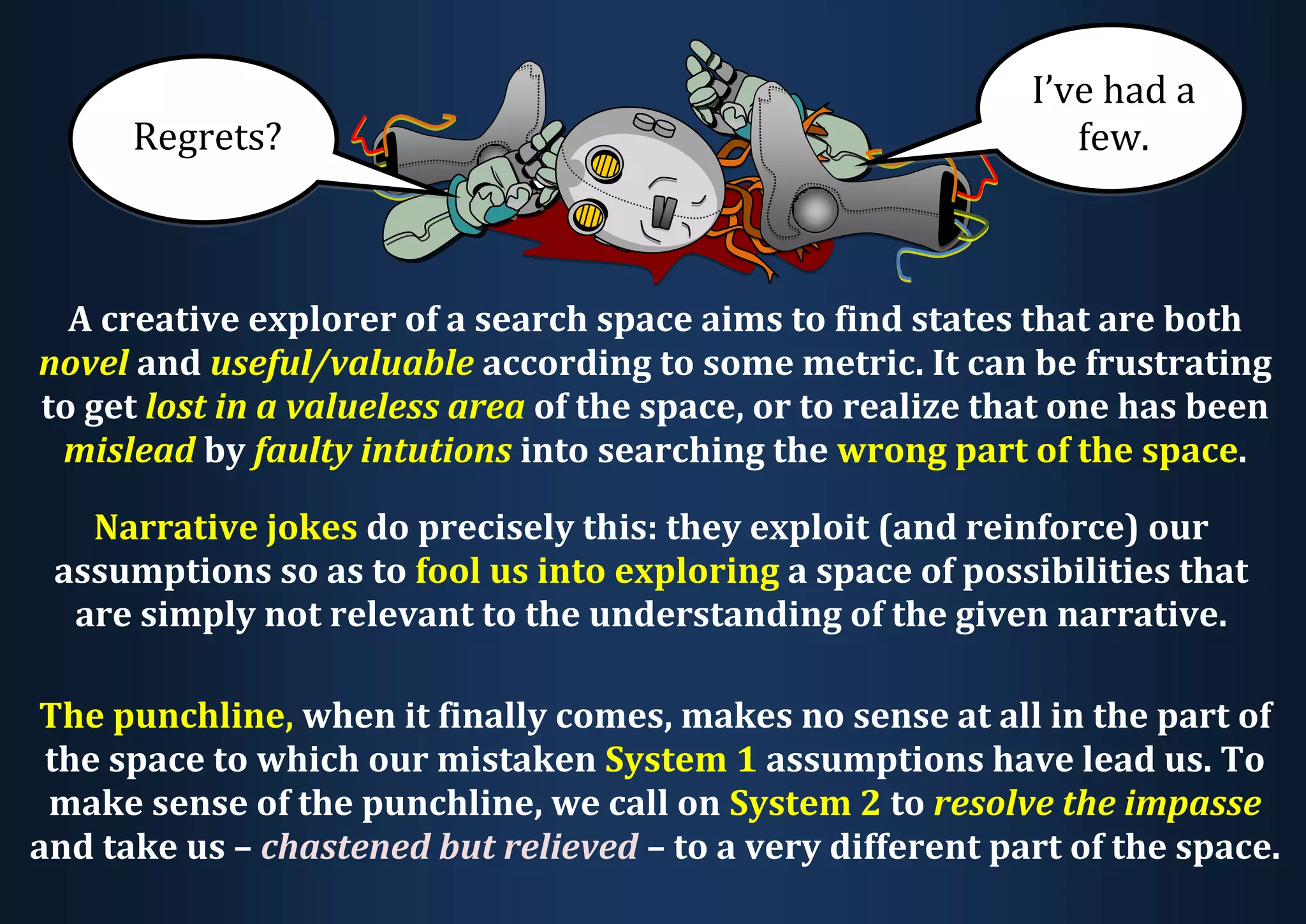

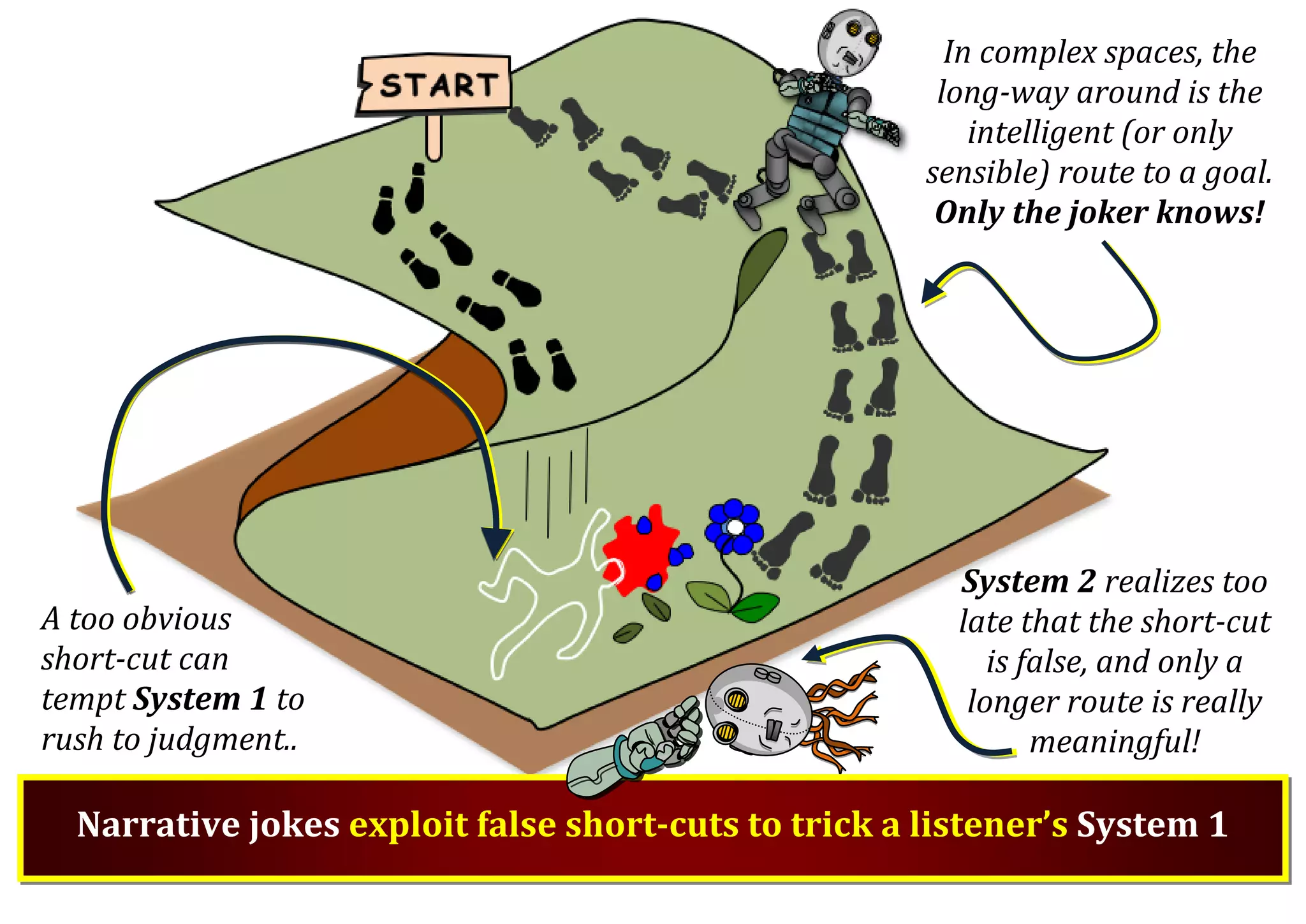

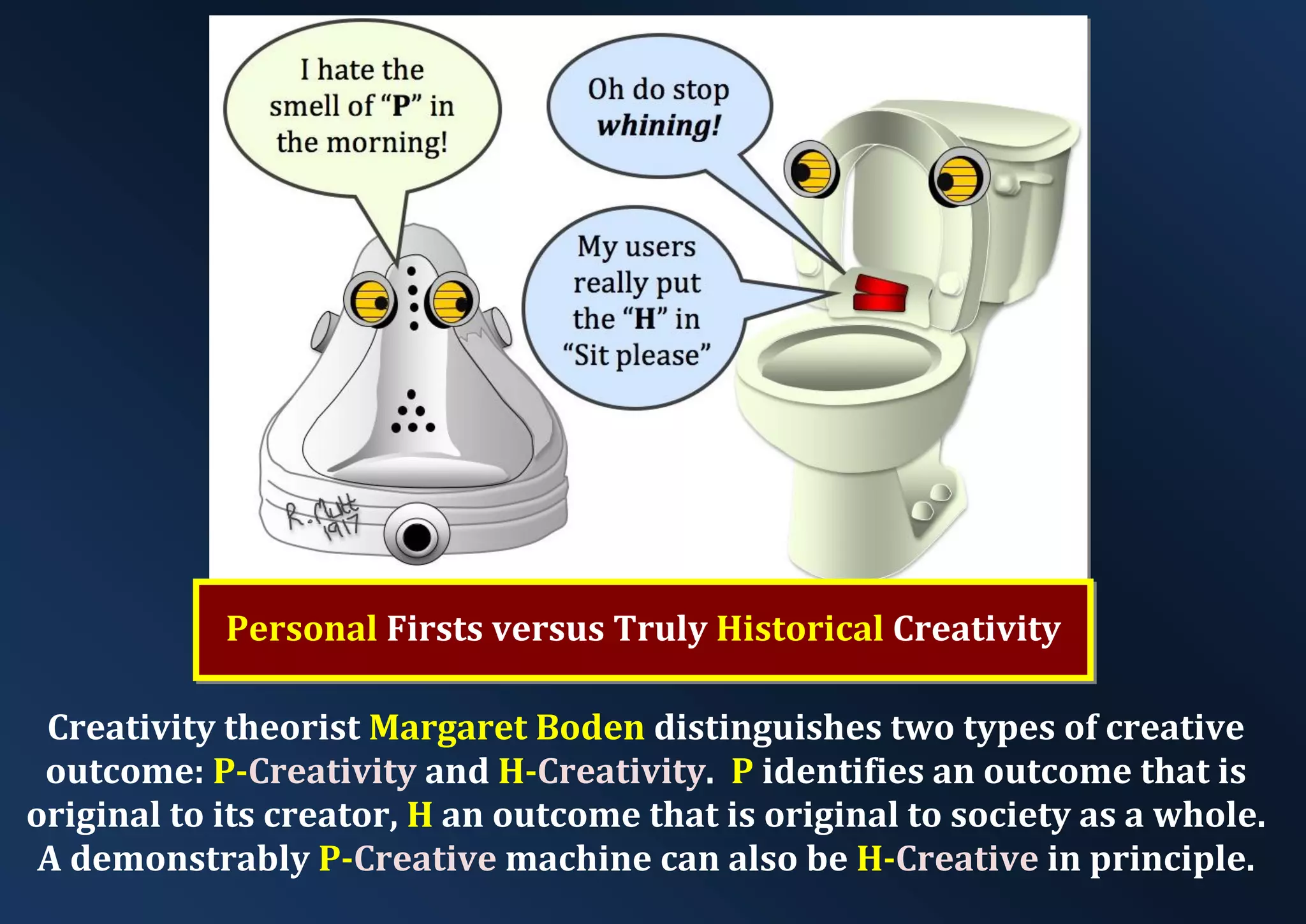

The document discusses computational creativity (cc) as the study of how machines can create art and ideas comparable to human creativity. It distinguishes between strong and weak cc systems, highlighting the role of humans in the creative process and examining how algorithms and software can influence creative expression. Additionally, the text explores the complexities of defining creativity, the relationship between machine learning and aesthetics, and the various cognitive strategies that can be employed in creative processes.