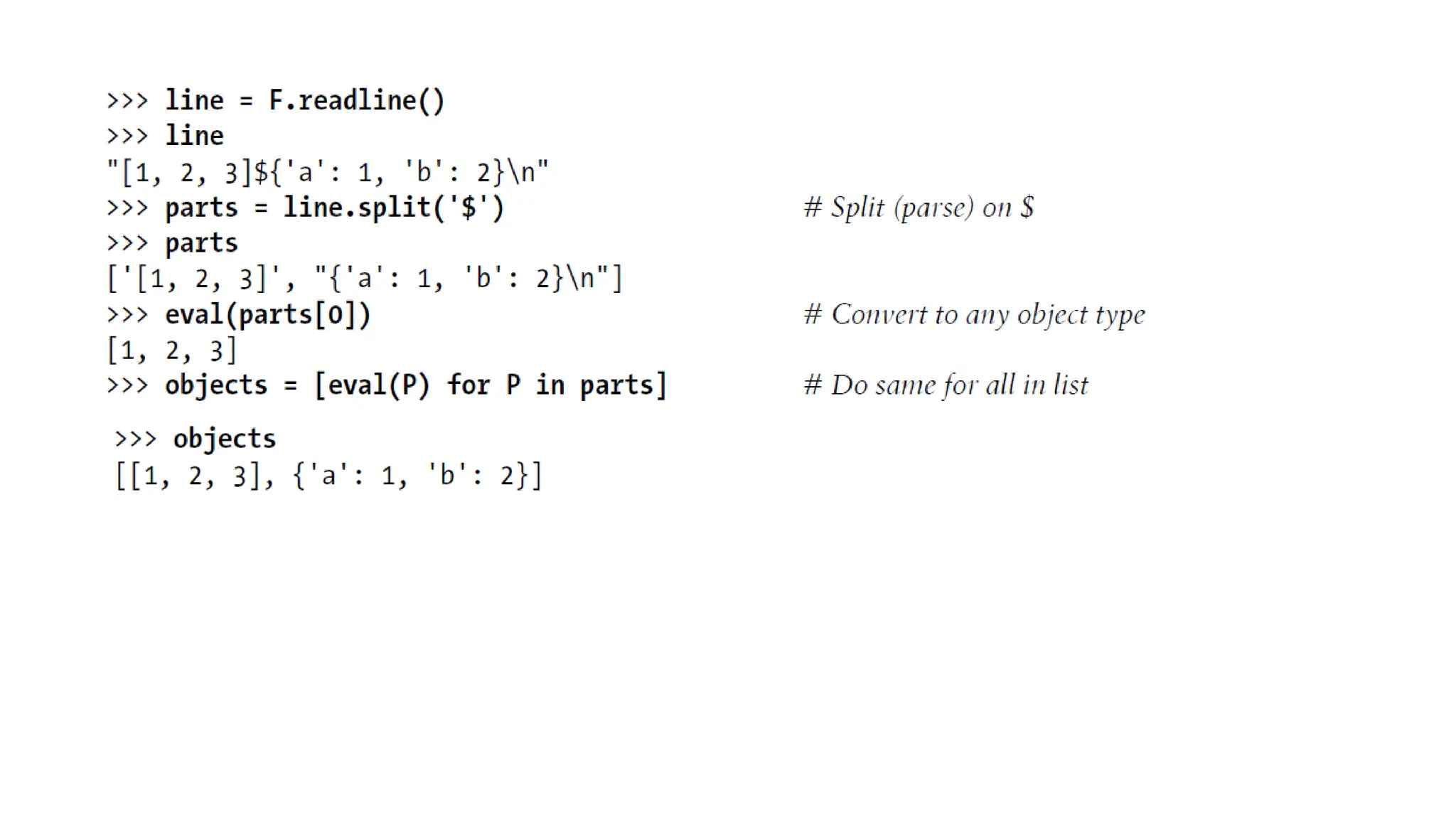

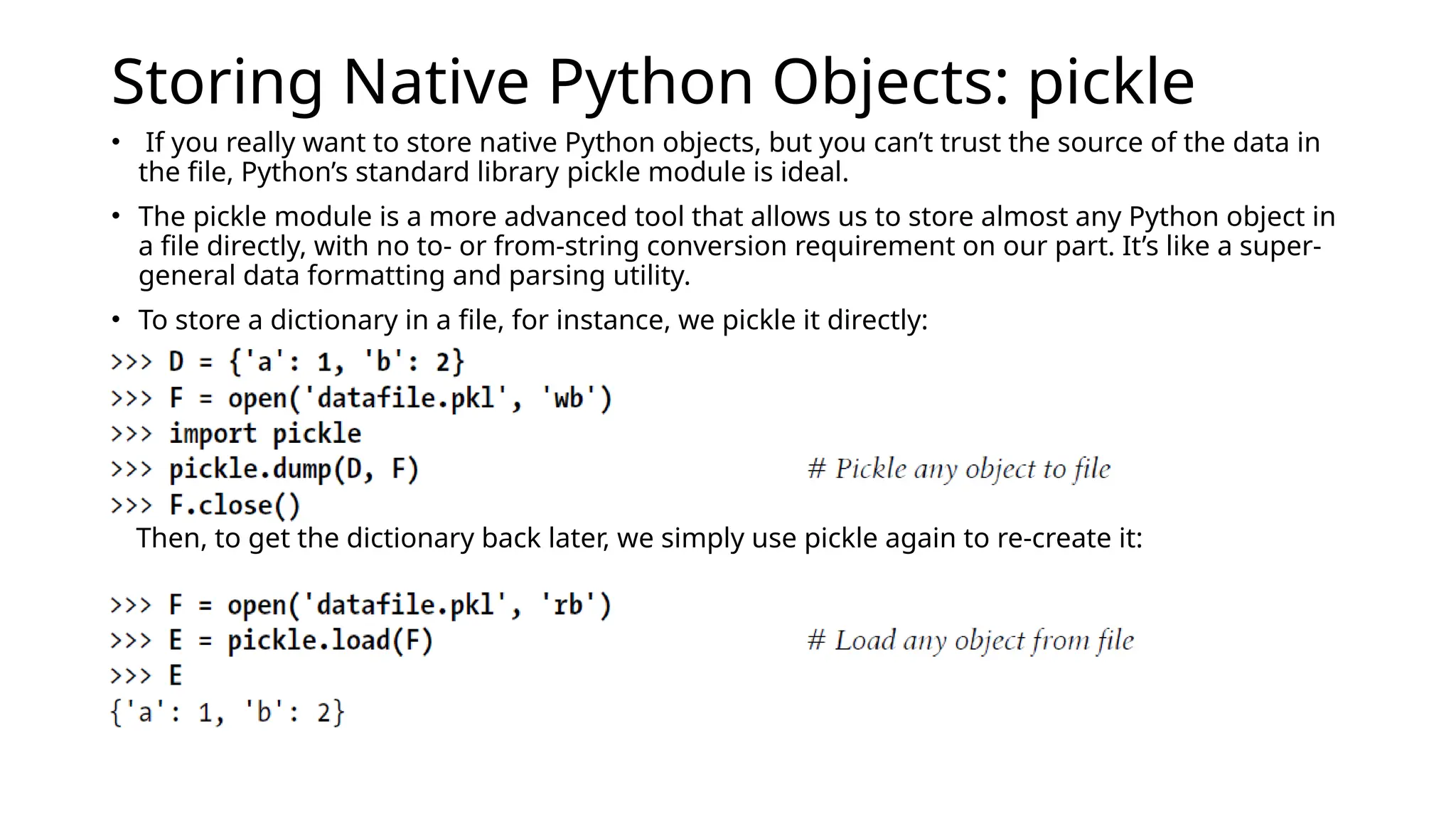

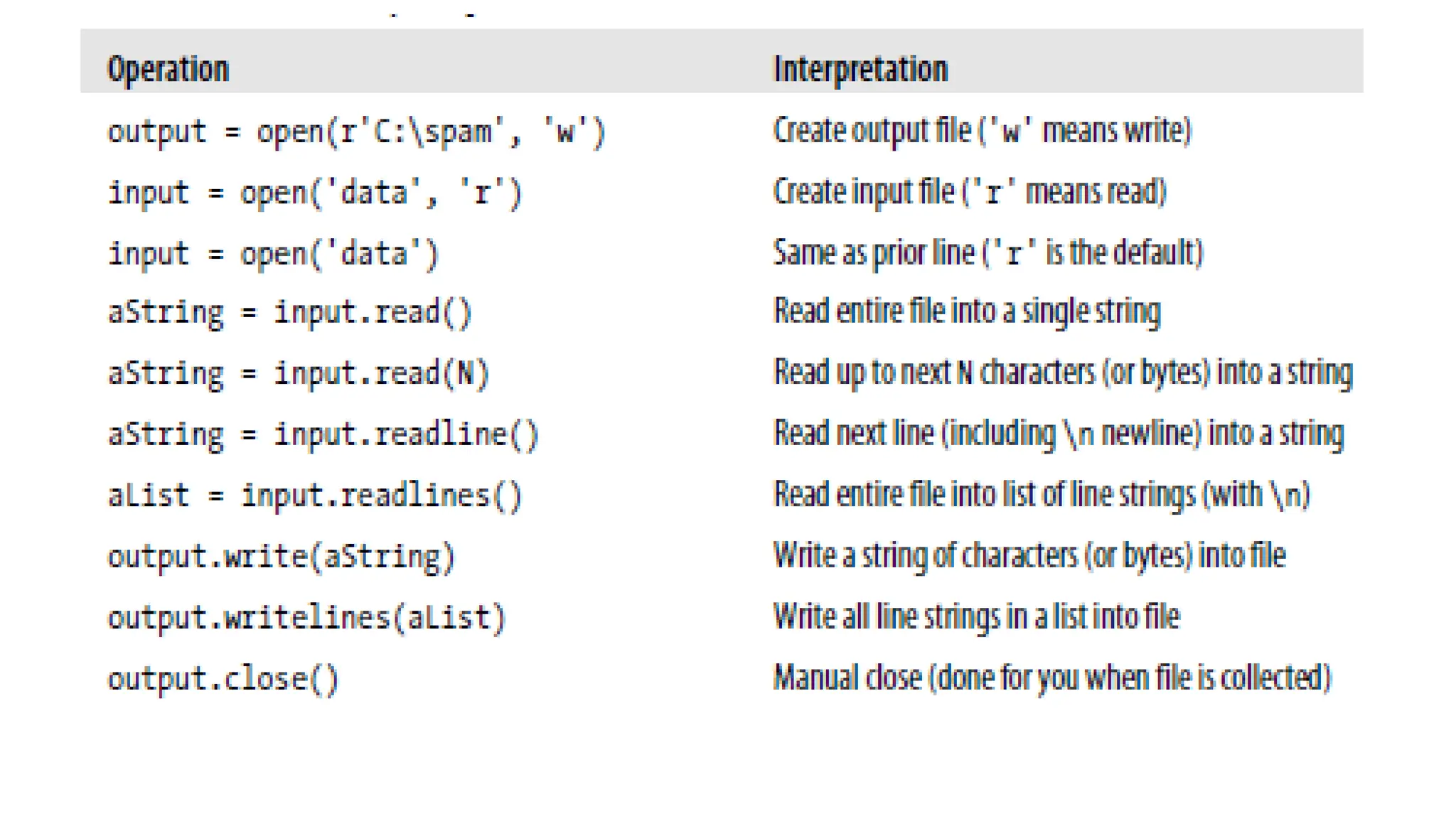

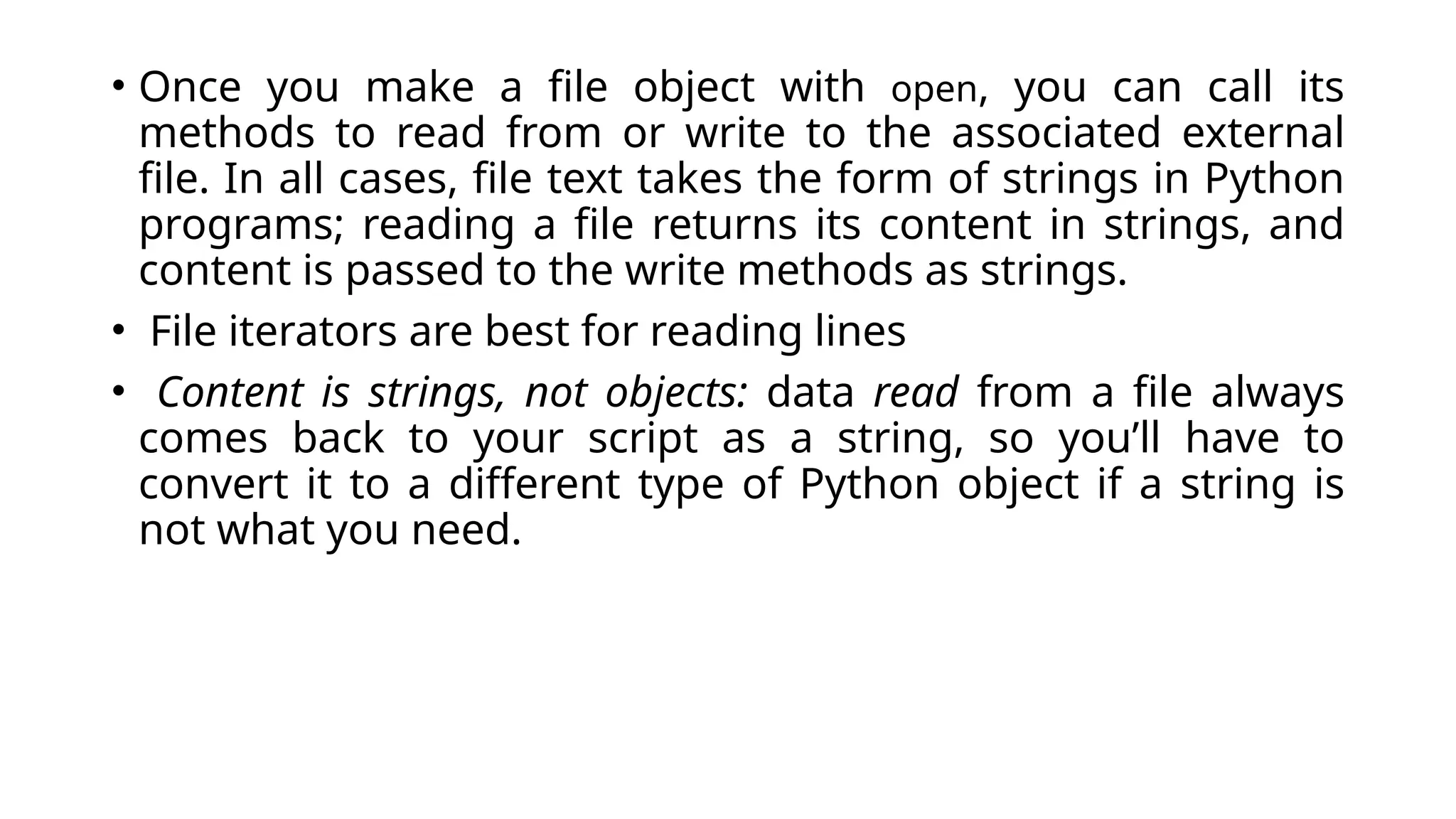

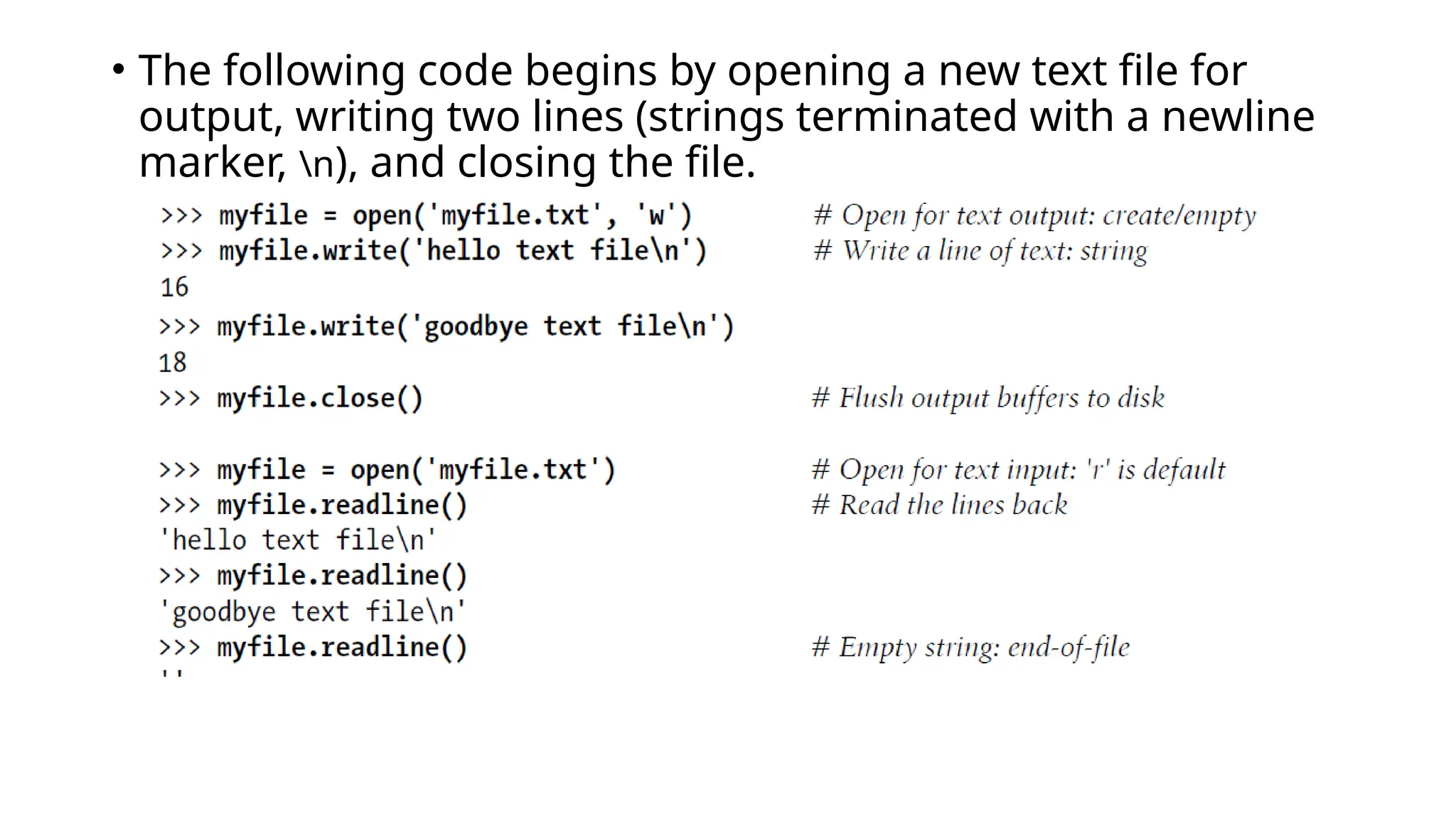

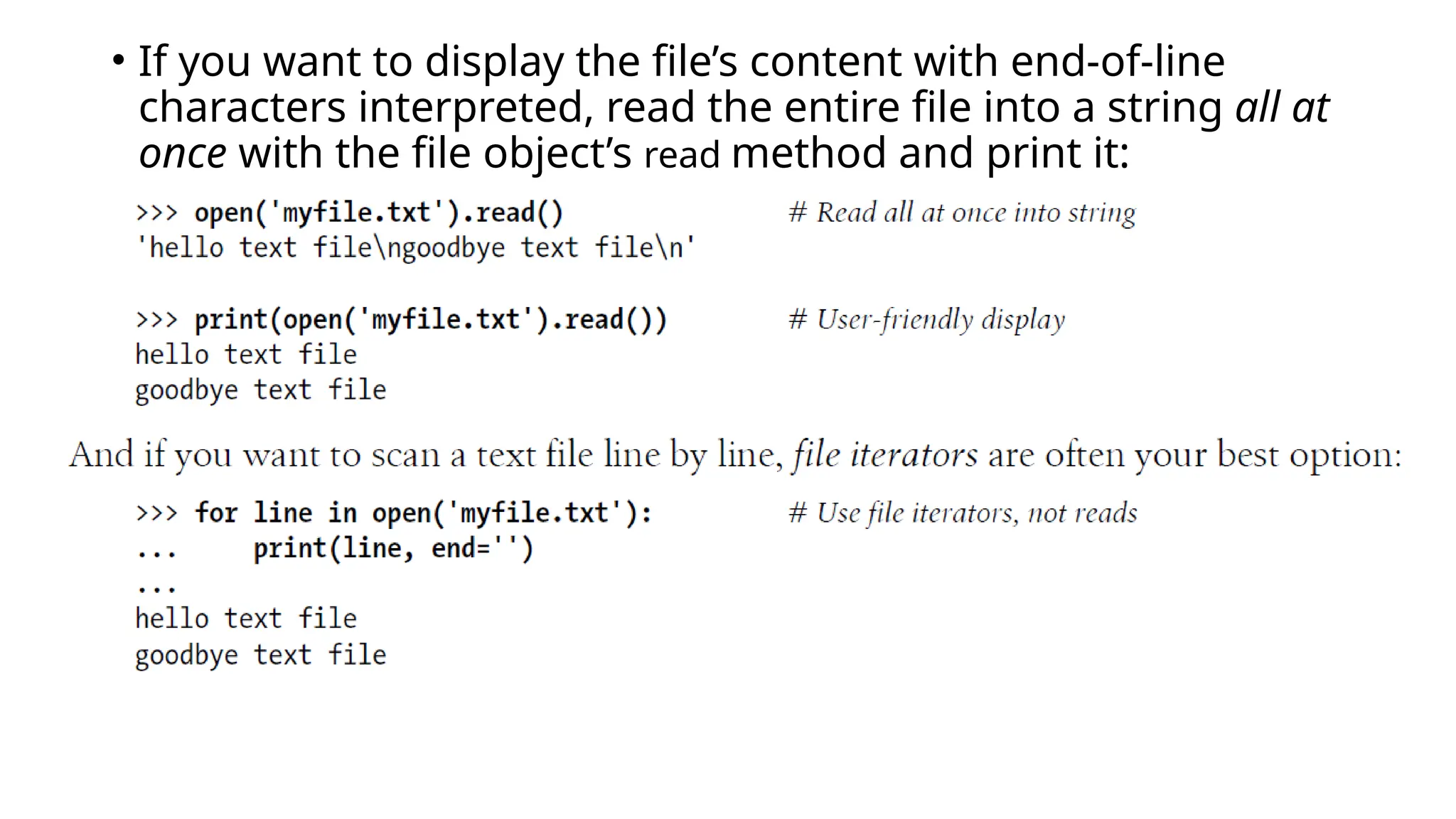

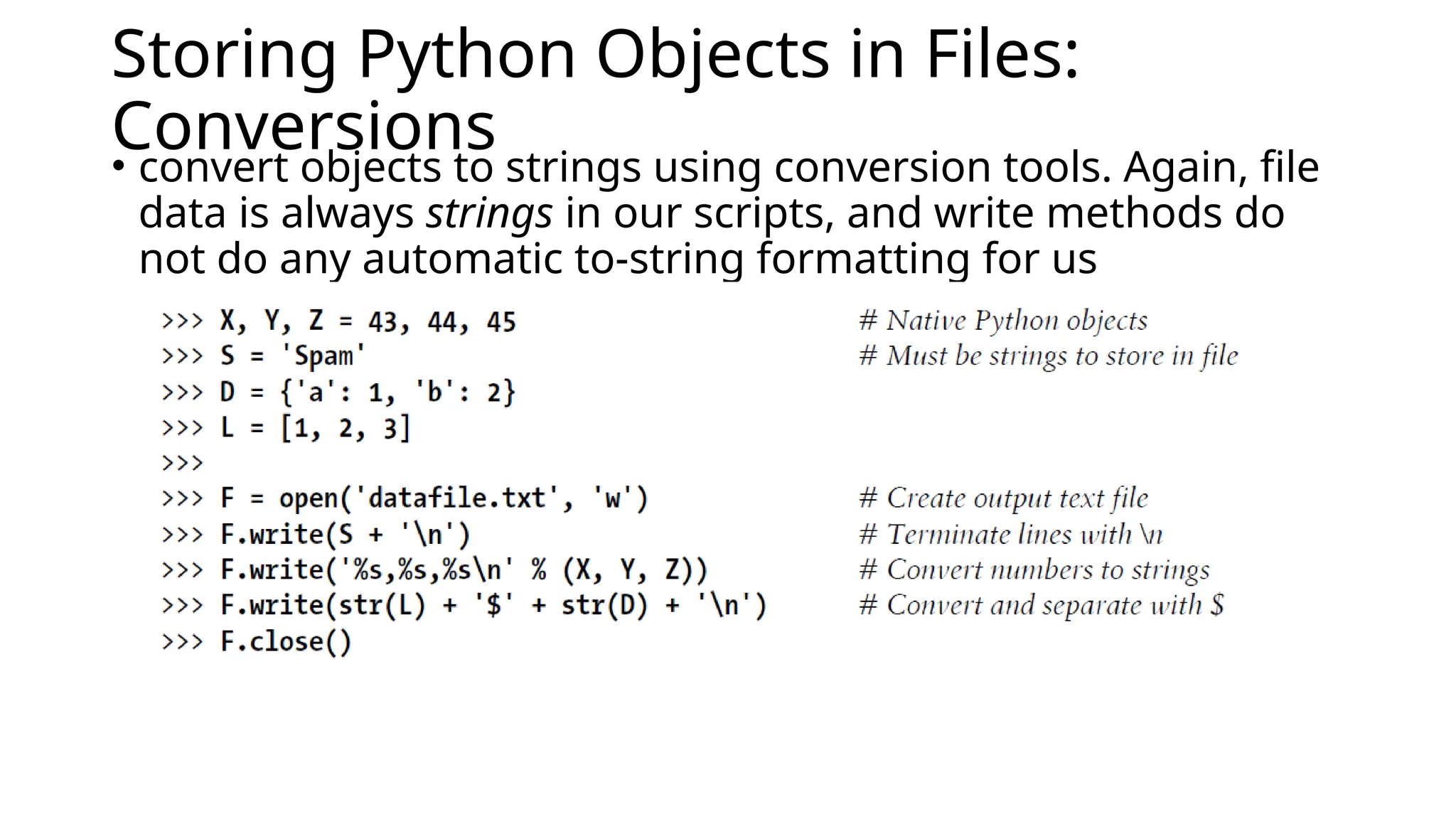

The document discusses file handling in Python, focusing on how to open files and perform read/write operations. It explains the use of the open function, processing modes, and methods for storing and converting data between strings and Python objects. It also introduces the pickle module for storing native Python objects directly without conversion.

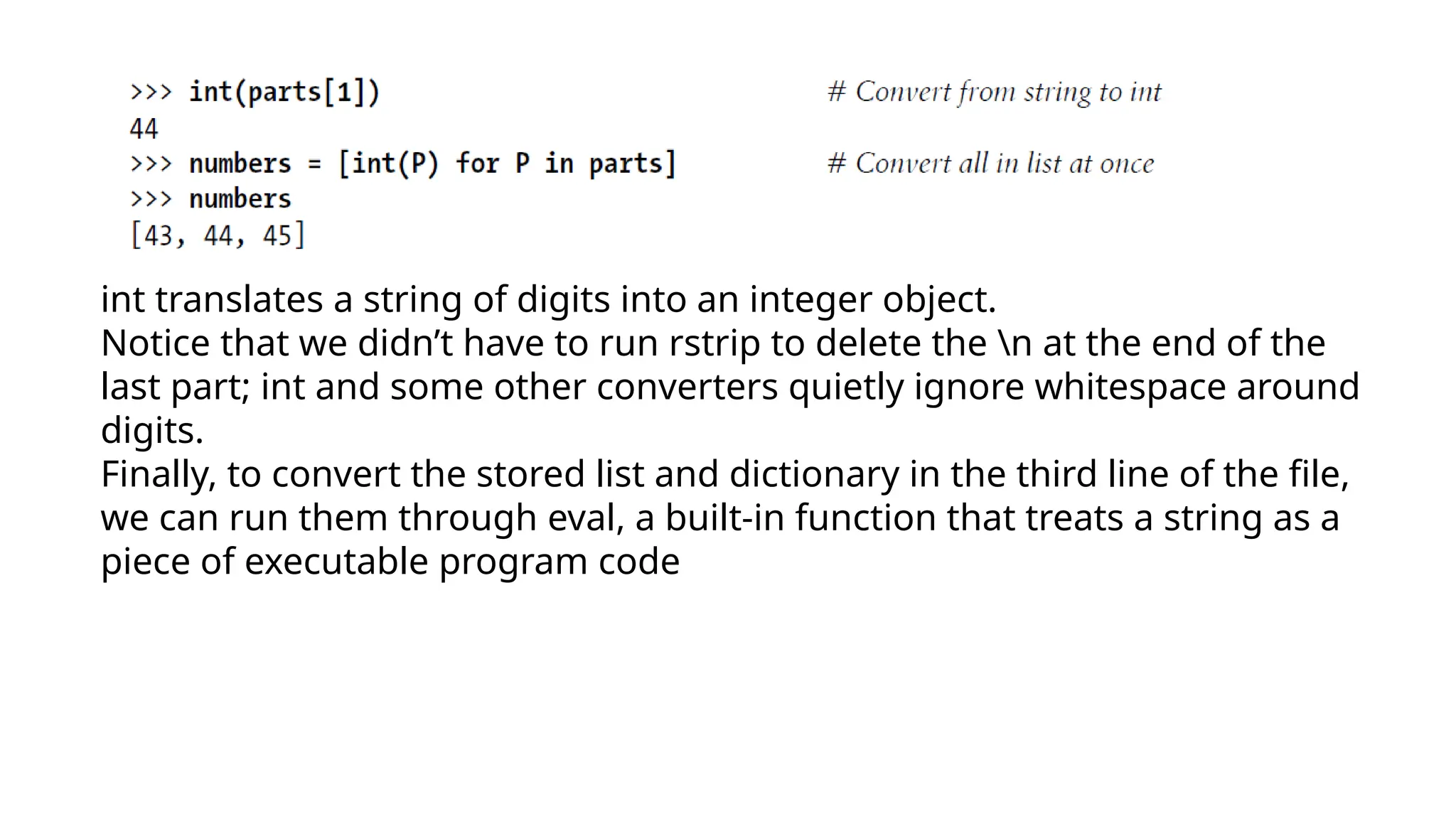

![For this first line, we used the string rstrip method to get rid of the trailing end-of-line character; a line[: 1] − slice would work, too, but only if we can be sure all lines end in the n character (the last line in a file sometimes does not). We still must convert from strings to integers, though, if we wish to perform math on these:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/files-241118115301-7977510f/75/Files-handling-using-python-language-pptx-11-2048.jpg)