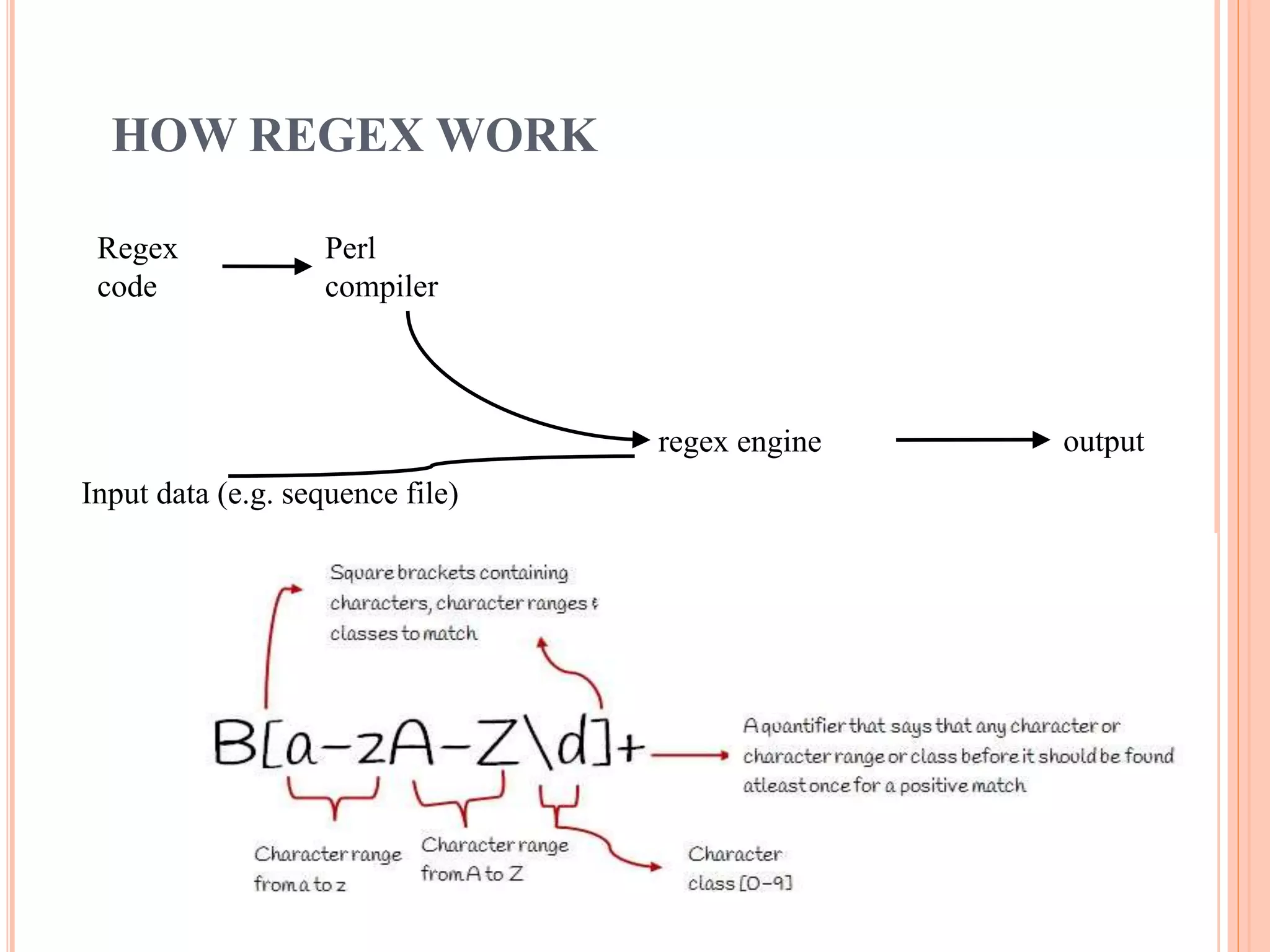

The document discusses various Perl concepts related to arrays, lists, hashes, strings, patterns and regular expressions. It provides definitions and examples of arrays, lists and hashes. It explains how to manipulate arrays and lists using built-in functions like shift, unshift and push. It also discusses iterating over lists using foreach, map and grep. The document then covers strings, patterns and regular expressions. It defines regular expressions and how they are used to define patterns in strings. It explains simple patterns and special characters used in regular expressions. It also discusses tools for manipulating strings using regular expression patterns, such as substitution, translation and split operations.

![ARRAYS It is collections of scalar data items which have an assigned storage space in memory, and can therefore be accessed using a variable name. The difference between arrays and hashes is that the constituent elements of an array are identified by a numerical index, which starts at zero for the first element. array always starts with @, eg: @days_of_week. An array stores a collection, and list is a collection, so it is natural to assign a list to an array. eg. @rainfall=(1.2, 0.4, 0.3, 0.1, 0, 0 , 0); This creates an array of seven elements. These can be accessed like $rainfall[0], $rainfall[1], .... $rainfall[6]. A list can also occur as elements of other list. @foo=(1,2,3, “string”); @foobar= (4, 5, @foo, 6); This gives foobar the value (4,5,1,2,3, “string”,6).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-2-2048.jpg)

![MANIPULATING ARRAYS Elements of an array are selected using C like square bracket syntax, eg: $bar=$foo[2]. The $ and [ ] make it clear that this instance foo is an element of the array foo, not the scalar variable foo. A group of contiguous elements is called a slice, and is accessed using simple syntax. @foo[1..3] Is the same as the list ($foo[1],$foo[2],$foo[3]) The slice can be used as the destination of the assignment eg:@foo[1..3]= (“hop”, “skip”, “jump”); Array variables and lists can be used interchangeably in almost any sensible situation: $front=(“bob”, “carol”, “ted”, “alice”)[0]; @rest=(“bob”, “carol”, “ted”, “alice”) [1..3]; or even @rest=qw/bob carol ted alice/[1..3]; Elements of an array can be selected by using another array selector. @foo =(7, “fred”, 9); @bar=(2,1,0); then @foo=@foo[@bar];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-3-2048.jpg)

![STAGES 1. The characters | ( ) [ { ^ $ * + ? . are meta characters with special meanings in regular expression. To use metacharacters in regular expression without a special meaning being attached, it must be escaped with a backslash. ] and } are also metacharacters in some circumstances. 2. Apart from meta characters any single character in a regular expression /cat/ matches the string cat. 3. The meta characters ^ and $ act as anchors: ^ -- matches the start of the line $ -- matches the end of the line. so regex /^cat/ matches the string cat only if it appears at the start of the line. /cat$/ matches only at the end of the line. /^cat$/ matches the line which contains the string cat and /^$/ matches an empty line. 4. The meta character dot (.) matches any single character except newline, so/c.t/ matches cat,cot,cut, etc.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-14-2048.jpg)

![STAGES 5. A character class is set of characters enclosed in square brackets. Matches any single character from those listed. So /[aeiou]/- matches any vowel /[0123456789]/-matches any digit Or /[0-9]/ 6. A character class of the form /[^....]/ matches any characters except those listed, so /[^0-9]/ matches any non digit. 7. To remove the special meaning of minus to specify regular expression to match arithmetic operators. /[+-*/]/ 8. Repetition of characters in regular expression can be specified by the quantifiers * -- zero or more occurrences + -- one or more occurrences ? – zero or more occurrences 9. Thus /[0-9]+/ matches an unsigned decimal number and /a.*b/ matches a substring starting with ‘a’ and ending with ‘b’, with an indefinite number of other characters in between.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-15-2048.jpg)

![FACILITIES 1. Alternations | If RE1,RE2,RE3 are regular expressions, RE1|RE2|RE3 will match any one of the components. 2. Grouping- ( ) Round Brackets can be used to group items. /pitt the (elder|younger)/ 3. Repetition counts Explicit repetition counts can be added to a component of regular expression /(wet[]){2}wet/ matches ‘ wet wet wet’ Full list of possible count modifiers are {n} – must occur exactly n times {n,} –must occur at least n times {n,m}- must occur at least n times but no more than m times. 4. Regular expression Simple regex to check for an IP address: ^(?:[0-9]{1,3}.){3}[0-9]{1,3}$](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-16-2048.jpg)

![SPLIT Syntax of split split REGEX, STRING will split the STRING at every match of the REGEX. split REGEX, STRING, LIMIT where LIMIT is a positive number. This will split the STRING at every match of the REGEX, but will stop after it found LIMIT- 1 matches. So the number of elements it returns will be LIMIT or less. split REGEX - If STRING is not given, splitting the content of $_, the default variable of Perl at every match of the REGEX. split without any parameter will split the content of $_ using /s+/ as REGEX. Simple cases split returns a list of strings: use Data::Dumper qw(Dumper); # used to dump out the contents of any variable during the running of a program my $str = "ab cd ef gh ij"; my @words = split / /, $str; print Dumper @words; The output is: $VAR1 = [ 'ab', 'cd', 'ef', 'gh', 'ij' ];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-24-2048.jpg)

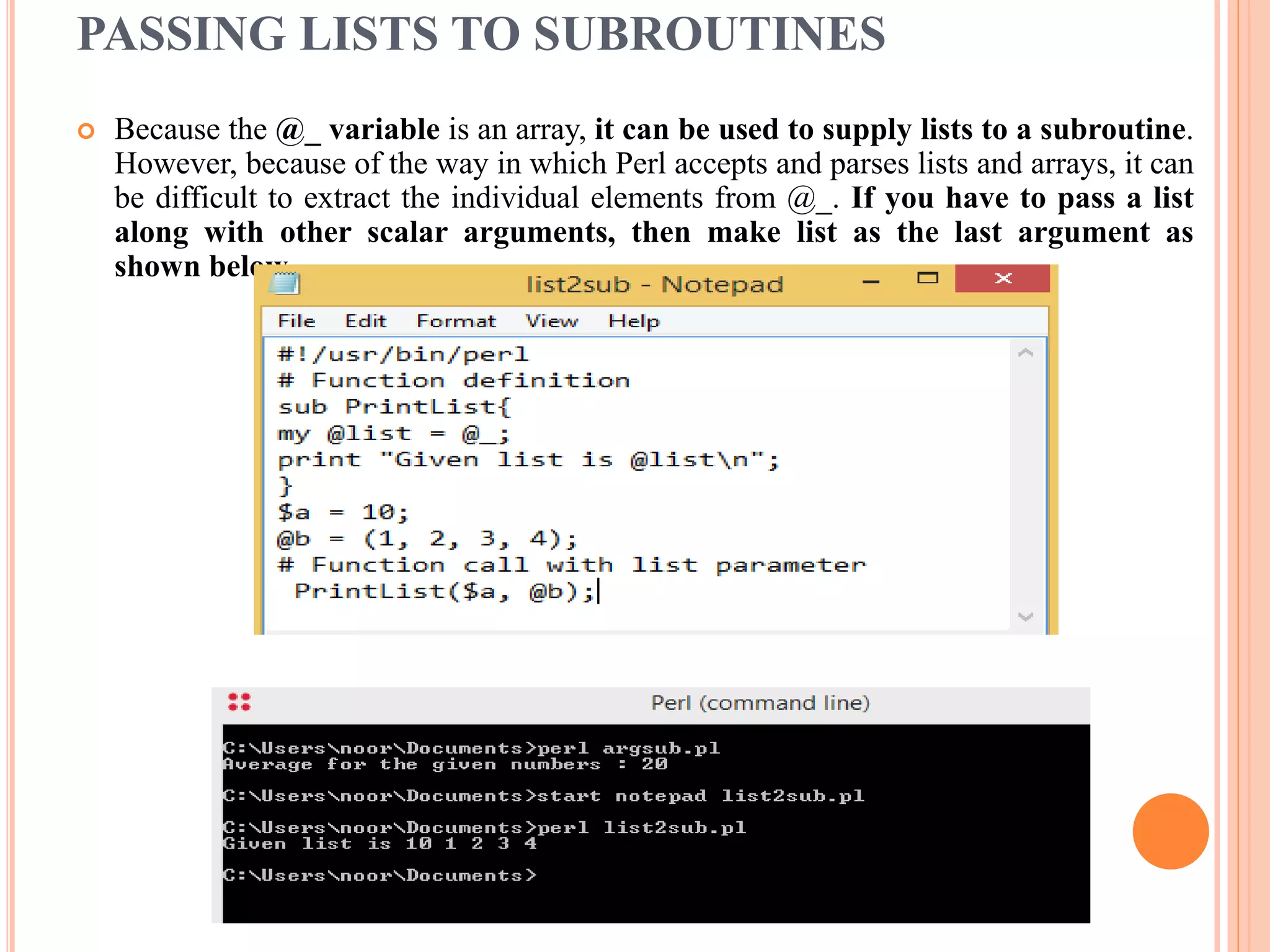

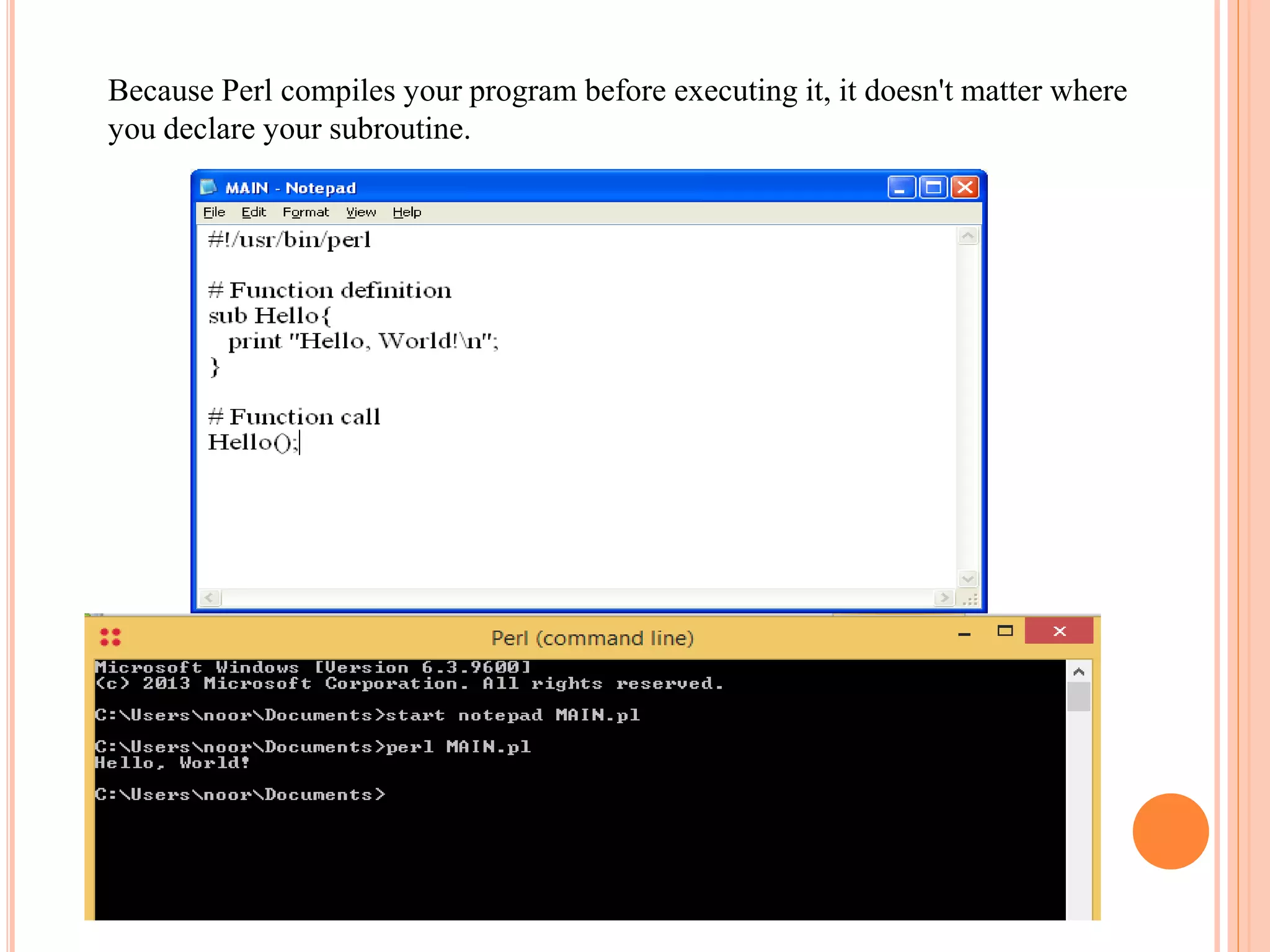

![PASSING ARGUMENTS TO A SUBROUTINE You can pass various arguments to a subroutine like you do in any other programming language and they can be accessed inside the function using the special array @_. Thus the first argument to the function is in $_[0], the second is in $_[1], and so on. You can pass arrays and hashes as arguments like any scalar but passing more than one array or hash normally causes them to lose their separate identities. So we will use references to pass any array or hash. Let's try the following example, which takes a list of numbers and then prints their average −](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1-arraylistsandhashes-170313141646/75/Unit-1-array-lists-and-hashes-30-2048.jpg)